When we talk about country club prison sentences, we tend to imagine a marginal amount of time spent on the inside, though the phrase sounds like an extended vacation. Napoleon Bonaparte—exiled to the island of St. Helena for his crimes against Europe—got the full treatment, what some might even call a sweetheart deal. As the Public Domain Review notes, “the British had agreed to provide Le Petit Caporal with plentiful wine, meat, and musical instruments.” He was given his own comfortable lodgings, a spacious country house, though it’s said to have been draughty and full of rats.

On the other hand, Napoleon had to foreswear “what he most craved—family, power, Europe,” for a condition of extreme isolation. The loss weighed heavily. After spending six years 1200 miles from shore, he died, some say of poisoning, but others say of boredom. Of his few amusements, conversing with Count Emmanuel de Las Cases—“historian and loyal supporter who had been allowed to voyage with him to Saint Helena”—proved most stimulating. Prevented from receiving newspapers in French, he longed to read the few he found in English.

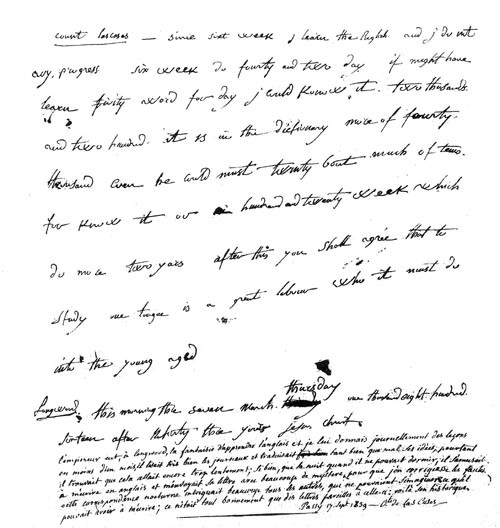

Las Cases endeavored to teach Napoleon the language of his jailers, and the former Emperor struggled mightily to learn it. After three months on the island, he spent the following three studying every day, eventually producing translations from his French like that below:

When will you be wise

Never as long as j should be in this isle

But j shall become wise after having passed the line

When j shall land in France j shall be very content…My wife shall come near to me, my son shall be great and strong if he will be able to trink a bottle of wine at dinner j shall [toast] with him… / The women believe they [are] ever prety / The time has not wings / When you shall come, you shall see that j have ever loved you.

Eight pages in Napoleon’s own hand remain from his time as a student of English on St. Helena in the first few months of 1816. They are “some of the most evocative documents we have from Napoleon’s time” on the island, the Fondation Napoleon writes, bearing “poignant witness to the frustration Napoleon felt in exile…. It is tempting to read a refusal of exile in these sheets, both in the sentences themselves, and in Napoleon’s insistent use of ‘j’ (as in the French ‘je’) rather than the English ‘I.’”

In one letter that survives from March 7, 1816 (see it scanned above), written for Las Cases to correct the following day, Napoleon takes stock of his progress, or lack thereof.

Count lascases — Since sixt week j learn the Englich and j do not any progress. Six week do fourty and two day. If might have learn fivity word four day I could know it two thusands and two hundred. It is in the dictionary more of fourty thousand; even he could must twinty bout much of tems for know it our hundred and twenty week, which do more two yars. After this you shall agrée that to study one tongue is a great labour who it must do into the young aged.

Las Cases reports that his student “had an extraordinary intelligence but a very bad memory.” Grammar came much more easily than vocabulary. His frustration over being “imprisoned in the middle of this language” is recorded in Las Cases’ Mémorial de Sainte-Hélène, a record of his fifteen months on the island with Napoleon. The book became “a publishing sensation” and would “do much,” the Public Domain Review writes, “to turn the perception of Napoleon from a dictator into a liberator.”

Related Content:

Napoleon’s Kindle: See the Miniaturized Traveling Library He Took on Military Campaigns

Vintage Photos of Veterans of the Napoleonic Wars, Taken Circa 1858

Napoleon: The Greatest Movie Stanley Kubrick Never Made

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

English was, however, Napoleon‘s second forreign languge. His first was French, which he was tought as a young man in Autun/Burgundy whereas his mothertounge was Corsican a variation of Italian.