How long has mankind dreamed of an international language? The first answer that comes to mind, of course, dates that dream to the time of the Biblical story of the Tower of Babel. If you don’t happen to believe that humanity was made to speak a variety of mutually incomprehensible tongues as punishment for daring to build a tower tall enough to reach heaven, maybe you’d prefer a date somewhere around the much later development of Esperanto, the best-known language invented specifically to attain universality, in the late 19th century. But look ahead a few decades past that and you find an intriguing example of a language created to unite the world without using words at all: International System Of Typographic Picture Education, or Isotype.

“Nearly a century before infographics and data visualization became the cultural ubiquity they are today,” writes Brain Pickings’ Maria Popova, “the pioneering Austrian sociologist, philosopher of science, social reformer, and curator Otto Neurath (December 10, 1882–December 22, 1945), together with his not-yet-wife Marie, invented ISOTYPE — the visionary pictogram language that furnished the vocabulary of modern infographics.”

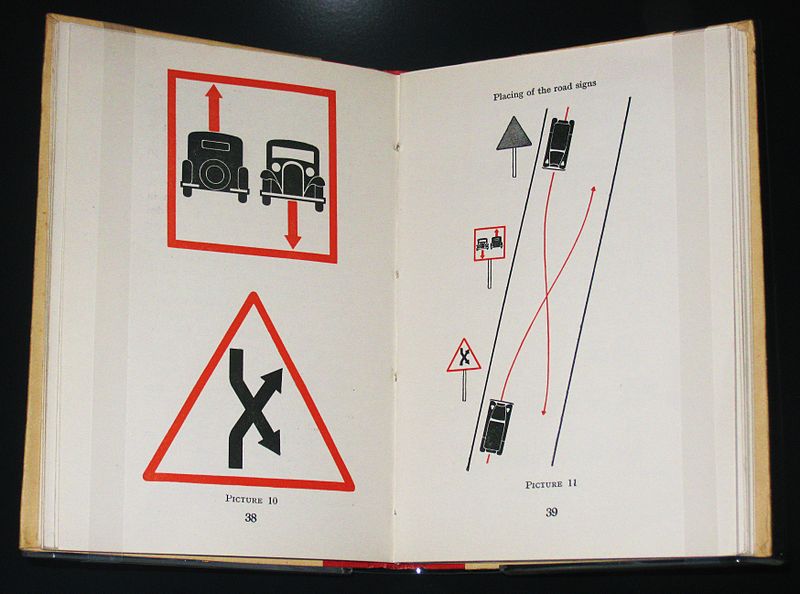

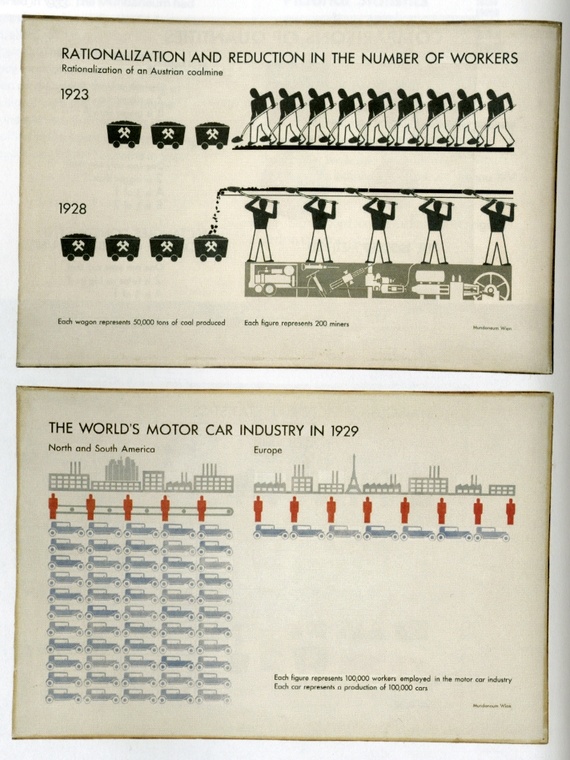

First known as the Vienna Method of Pictorial Statistics, Isotype’s initial development began in 1926 at Vienna’s Gesellschafts- und Wirtschaftsmuseum (or Social and Economic Museum), of which Neurath was the founding director. There he began to assemble something like a design studio team, with the mission of creating a set of pictorial symbols that could render dense social, scientific technological, biological, and historical information legible at a glance.

Neurath’s most important early collaborator on Isotype was surely the woodcut artist Gerd Arntz, at whose site you can see the more than 4000 pictograms he created to symbolize “key data from industry, demographics, politics and economy.” Arntz designed them all in accordance with Neurat’s belief that even then the long “virtually illiterate” proletariat “needed knowledge of the world around them. This knowledge should not be shrined in opaque scientific language, but directly illustrated in straightforward images and a clear structure, also for people who could not, or hardly, read. Another outspoken goal of this method of visual statistics was to overcome barriers of language and culture, and to be universally understood.”

By the mid-1930s, writes The Atlantic’s Steven Heller in an article on the book Isotype: Design and Contexts 1925–1971, “with the Nazi march into Austria, Neurath fled Vienna for Holland. He met his future wife Marie Reidemeister there and after the German bombing of Rotterdam the pair escaped to England, where they were interned on the Isle of Man. Following their release they established the Isotype Institute in Oxford. From this base they continued to develop their unique strategy, which influenced designers worldwide.” Today, even those who have never laid eyes on Isotype itself have extensively “read” the visual languages it has influenced: Gizmodo’s Alissa Walker points to the standardized icons created in the 70s by the U.S. Department of Transportation and the American Institute of Graphic Arts as well as today’s emoji — probably not exactly what Neurath had in mind as the language of Utopia back when he was co-founding the Vienna Circle, but nevertheless a distant cousin of Isotype in “its own adorable way.”

via Brain Pickings

Related Content:

The Art of Data Visualization: How to Tell Complex Stories Through Smart Design

You Could Soon Be Able to Text with 2,000 Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs

Say What You Really Mean with Downloadable Cindy Sherman Emoticons

The Hobo Code: An Introduction to the Hieroglyphic Language of Early 1900s Train-Hoppers

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

I learned about Isotype a few years ago when the band OMD made a song about it, with a video packed with Isotype: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gp_Du6uO9V4