If you’ve heard of Buckminster Fuller, you’ve almost certainly heard the word “Dymaxion.” Despite its strong pre-Space Age redolence, the term has somehow remained compelling into the 21st century. But what does it mean? When Fuller, a self-described “comprehensive, anticipatory design scientist,” first invented a house meant practically to reinvent domestic living, Chicago’s Marshall Field and Company department store put a model on display. The company “wanted a catchy label, so it hired a consultant, who fashioned ‘dymaxion’ out of bits of ‘dynamic,’ ‘maximum,’ and ‘ion,’ ” writes The New Yorker’s Elizabeth Kolbert in a piece on Fuller’s legacy. “Fuller was so taken with the word, which had no known meaning, that he adopted it as a sort of brand name.” After the Dymaxion House came the Dymaxion Vehicle, the Dymaxion Map, and even the two-hour-a-day Dymaxion Sleep Plan.

“As a child, Fuller had assembled scrapbooks of letters and newspaper articles on subjects that interested him,” Kolbert writes. “When, later, he decided to keep a more systematic record of his life, including everything from his correspondence to his dry-cleaning bills, it became the Dymaxion Chronofile.” The Dymaxion Chronofile now resides in the R. Buckminster Fuller Collection at Stanford University, a place that has merited the attention of no less a guide to the fascinating corners of the world than Atlas Obscura.

“The files go back to when he was four-years-old, but he only seriously started the archive in 1917,” writes that site’s Allison C. Meier. “From then until his death in 1983 he collected everything from each day, with ingoing and outgoing correspondence, newspaper clippings, drawings, blueprints, models, and even the mundane ephemera like dry cleaning bills.” Fuller added to the Dymaxion Chronofile not just every day but, from the year 1920 until his death in 1983, every fifteen minutes.

In 1962 Fuller described the Dymaxion Chronofile as what would happen “if somebody kept a very accurate record of a human being, going through the era from the Gay ’90s, from a very different kind of world through the turn of the century — as far into the twentieth century as you might live.” Using himself as the case subject for the project (as he did for many projects, which led him to nickname himself “Guinea Pig B”) meant that “I could not be judge of what was valid to put in or not. I must put everything in, so I started a very rigorous record.” Open Culture’s own Ted Mills has written elsewhere about the rigors of storing and maintaining that record in archive form over the decades since Fuller’s death, and now, as with so much Fuller did, the Dymaxion Chronofile stands as both a compelling oddity and proof of real, if askew, prescience. After all, how many of us have taken to documenting our own lives online with nearly equal intensity — and how many of us do it even more often than every fifteen minutes?

Related Content:

Buckminster Fuller’s Map of the World: The Innovation that Revolutionized Map Design (1943)

A Harrowing Test Drive of Buckminster Fuller’s 1933 Dymaxion Car: Art That Is Scary to Ride

Everything I Know: 42 Hours of Buckminster Fuller’s Visionary Lectures Free Online (1975)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

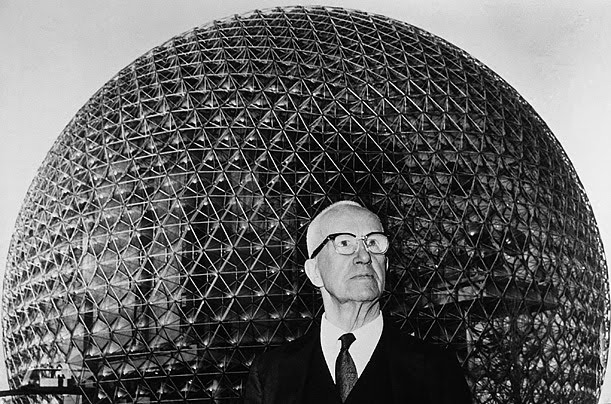

Let’s not forget Mr. Fuller’s participation to the international exhibition of Expo67, in Montréal that year… The USA pavilion was one of his greatest achievements.

As Fuller archivist Trevor Blake points out, Fuller was ahead of his time in keeping a chronofile (like a Facebook profile); doing a paleo diet (spinach and steak); jogging (the term was not yet invented); and of course being an early member of the “jet set” (42 times around the world? — something like that). He not only anticipated the future, he lived it.