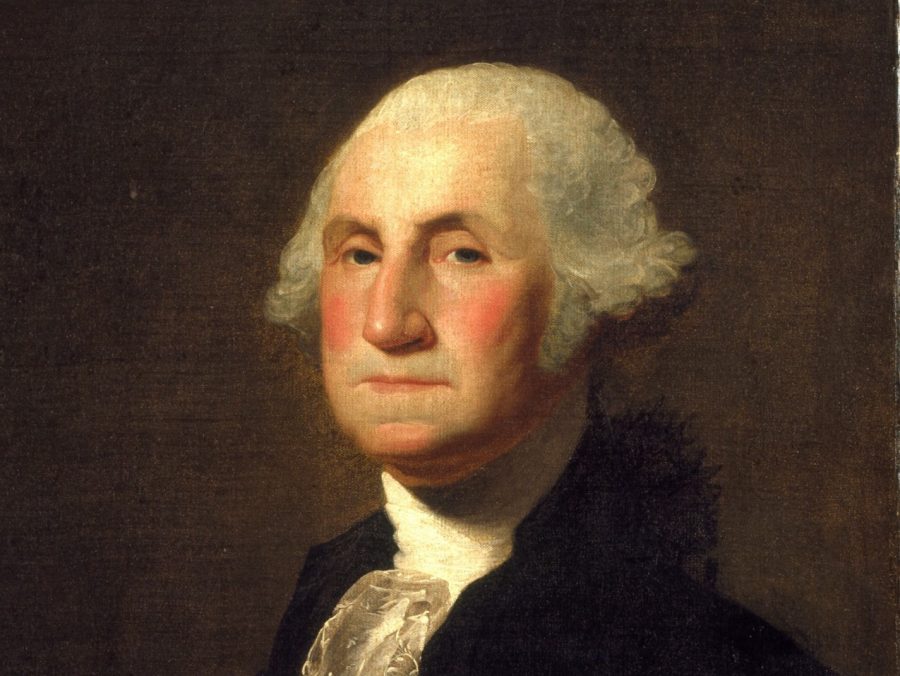

In the early United States, devout Christians who would impose their beliefs on others were in the minority among the country’s founders. Thomas Jefferson’s views on the subject are well-known. Much more conservative than Jefferson, fellow Virginian George Washington made frequent statements on religion as part of the essential texture of public life. But while Washington discussed religion as a communal affair with important social and political dimensions, like Jefferson he endorsed religious liberty and freedom of conscience and belief.

Washington went further in defense of religious minorities than the hugely influential theorist of religious toleration, John Locke. The principle of toleration was unique in Europe and England, where “state-sponsored religion was the norm,” as Newport, Rhode Island’s historic Touro Synagogue explains.

But the idea was usually taken to mean that “non-Christians were to be ‘tolerated’ for their beliefs” in a paternalist sense, “with the hope that ‘Jews, Turks, and Infidels” would become Christian.” Washington, however, declared:

It is now no more that toleration is spoken of, as if it was by the indulgence of one class of people, that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights. For happily the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves good citizens, in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.

These words come from Washington’s short 1790 letter to the “the Hebrew Congregation in Newport, Rhode Island,” the first in a series of letters written to citizens of Newport after he and then-secretary of state Jefferson made a visit. The address responds directly to a letter of welcome read to him on his arrival in the city by Moses Seixas, an official of the first Jewish congregation in Newport, which states:

Deprived as we heretofore have been of the invaluable rights of free Citizens, we now (with a deep sense of gratitude to the Almighty disposer of all events) behold a Government, erected by the Majesty of the People—a Government, which to bigotry gives no sanction, to persecution no assistance—but generously affording to All liberty of conscience, and immunities of Citizenship: deeming every one, of whatever Nation, tongue, or language, equal parts of the great governmental Machine….

As did many such proclamations, the document glosses the brutal contradiction of slavery, indigenous slaughter, and actual discrimination religious minorities faced. Nonetheless, the democratic principles Seixas outlined so accorded with Washington’s ideals that the first president repeated key phrases verbatim. This is no mere pandering. When Washington arrived in Newport in 1790, state legislatures were in the process of ratifying what was then the Third Amendment to the Constitution, which we know as the First, prohibiting the establishment of state religion and granting freedom of the press.

Arguments over religious liberty were fierce, and toleration had strict limits. In some states “the rights of minority groups such as Baptists, Presbyterians, Catholics and Quakers were restricted,” notes Touro. “In most states, non-Christians were denied the rights of full citizenship, such as holding public office. Even in religiously liberal Rhode Island, Jews were not allowed to vote.” While the First Amendment “did little to erase these injustices,” Washington’s letter set out ideal conditions in which the country’s “enlarged and liberal policy” granted “liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship” to all.

That Washington would make such claims in Rhode Island bears particular significance given that the state is “most noted as the place where religious freedom was actually born,” writes former Ambassador and UN Delegate John Loeb. The colony’s 1663 charter “set forth the first political entity in the world to separate the church from the state.” Washington’s statement one hundred and twenty-seven years later “applied—and continues to apply—to every American,” Loeb argues, despite its specific address “to a small group of Jewish citizens.” But that specific address matters. It promised inclusion and protection to a community that had faced centuries of terror.

As historian Melvin Urofsky writes, the letter “to the Hebrew Congregation,” like many other such statements made by the founders, “is a treasure to the entire nation”—a nation that “recognized,” at least in words, “diversity for what it was, one of the country’s greatest assets, and took as its motto E Pluribus Unum—Out of Many, One. The separation of church and state, and with it the freedom of religion enshrined in the First Amendment to the Constitution, has made the United States a beacon of hope to oppressed peoples everywhere.”

Read Washington’s concise “Letter to the Hebrew Congregation in Newport, Rhode Island” here.

Related Content:

Harvard Launches a Free Online Course to Promote Religious Tolerance & Understanding

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

“In the early United States, devout Christians who would impose their beliefs on other *white land-owning men* were in the minority among the country’s founders.” There. Fixed it.

“For happily the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance…” lol.

Glad that this author questioned that connection. Still it seems absurd that someone could be blinded by their own bigotries that they could say those words while killing indigenous people, enslaving black people, and subjugating women.

You’re absolutely right, June. The hypocrisy is staggering.

Very good post, but I do not agree with the comments posted thereafter. There is a difference between what society should aspire to and what can be practically achieved at any given moment of time. Recognizing that difference is not hypocrisy at all — it is wisdom.

Totally agree. Ascribing current morals and beliefs on people living hundreds of years ago is myopic. They existed within a society, as do we. Most likely, wherever you are on the current political spectrum is where you’d be in the past, so that if you’re a centrist now, you’d be a centrist in the 1700s. As we all know, centrist views back then included general (if grudging) acceptance of slavery, subjugation of indigenous populations and women, etc. To think you’d believe in the 1700s what you believe now is silly, Don’t fool yourselves into thinking you’d be a pioneering radical revolutionary back then. You almost certainly wouldn’t.

JV, I think you make a valid point. For example, virtually all cultures practiced slavery in some form or another throughout history until things began to change in the late eighteenth century. Notwithstanding that, I think many of the Founders were ill-disposed to the institution, but understood that insisting upon abolition at that time would have destroyed any possibility of forming a union among the states.

Hm, yes, measuring historical figures’ behavior against their loudly professed principles is anachronistic. Men of their time, and so on.…. It’s not like they personally benefitted from an institution they claimed to loathe and knew undermined their ideals. Maybe I’d buy their good faith if Washington had manumitted his slaves *before* his death, or Jefferson had done so at all (his own children excepted, of course). Surely we could at least agree the motives were mixed. Pragmatism and profit.

It is ahistorical at best to suggest that any given figure didn’t have the requisite tools to make moral decisions. At no point in history was there only one ideology available to choose from (let alone in the company of revolutionaries with thoughts of liberation).

For example: George Mason — “As much as I value an union of all the states, I would not admit the southern states into the union, unless they agreed to the discontinuance of this disgraceful trade, because it would bring weakness and not strength to the union.” and “The augmentation of slaves weakens the states; and such a trade is diabolical in itself, and disgraceful to mankind.” They knew that what they were doing was wrong, but it was making them very rich and very powerful.

Three hundred years from now, reactionaries may argue that people are wrong to judge today’s bigots by the moral values of a more liberated society, but they would be absolutely dead wrong.

When people argue that people can’t be held to moral standards above those of the dominant classes of their time and place, they are basically reiterating the Nuremberg defense. Harming people is evil no matter how much the ideological apparatuses of your society approve of it. This idea wasn’t an invention of the 20th century.

June, the point is not that the Founders lacked “the requisite tools to make moral decisions”. Rather, oftentimes, two or more entirely moral positions are in direct conflict and, as a consequence, compromise is necessary. To wit, a morally indefensible institution on one hand — albeit one practiced on every continent then — and, on the other, the moral imperative of forming a union capable of coexisting and preserving a fledgling independence. As Thomas Sowell is fond of saying, there are no solutions in life, only trade-offs.

“Morally indefensible,” and yet, here you are.