Who invented cyberpunk, that vivid subgenre of science fiction at the intersection of “high tech and low life”? Some put forth the name of William Gibson, whose 1984 novel Neuromancer crystallized many of the elements of cyberpunk that still characterize it today, even if it wasn’t the first example of all of them. And who, for that matter, invented science fiction? Brian Aldiss, a sci-fi writer and a respected scholar of the tradition, argued for Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein. “The seminal point about Frankenstein,” Aldiss writes, “is that its central character makes a deliberate decision. He succeeds in creating life only when he throws away dusty old authorities and turns to modern experiments in the laboratory.”

In other words, Victor Frankenstein uses science, which according to Aldiss had not propelled a narrative before Frankenstein’s publication in 1818. The novel came out, in an edition of just 500 three-volume copies, under the full title Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, and without any author’s name. Shelley’s decision to publish her work anonymously, with a preface by her husband Percy Bysshe Shelley, led readers to assume that the poet himself had written the book. Though he hadn’t, he had accompanied the then-18-year-old Mary Shelley on the trip to Switzerland where she came up with the story. There, kept indoors by foul weather at Lake Geneva’s Villa Diodati, the couple and Lord Byron, whom they had come to visit, binge-read ghost stories to one another until they decided to each write an original one.

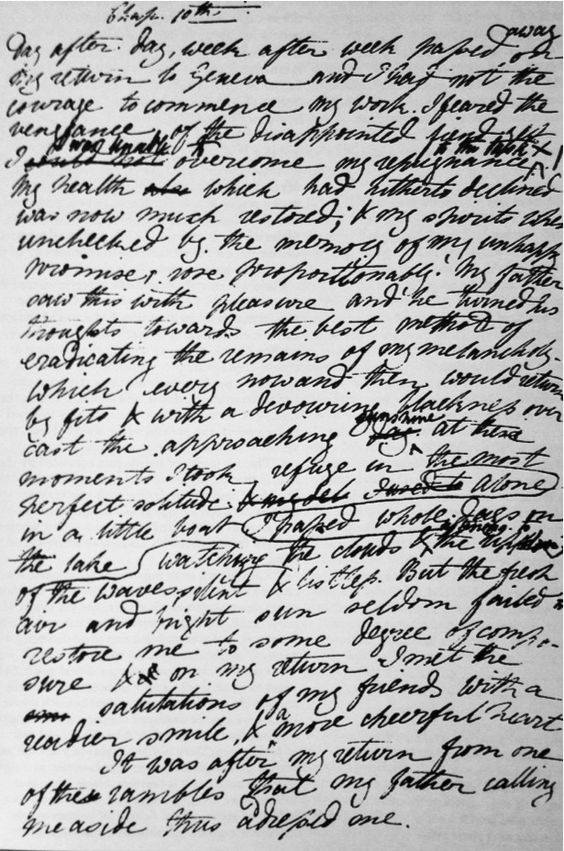

It took Shelley some time to come up with an idea, but when inspiration finally struck, it brought on an unignorable vision. “I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together,” Shelley writes in her introduction to the non-anonymous 1831 edition of Frankenstein. “I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion.” She thus began to write her story, first in short form and later, with Percy’s encouragement, expanding it into a novel. A few days ago, Gibson retweeted a page of one of Shelley’s handwritten manuscripts, adding only, “This is, literally, ground zero of science fiction.”

The original tweeter of the image, someone called Laura N, describes it as “the first page of Frankenstein,” although its text page appears in the published book as the first page of its eighteenth chapter. She also links to the Shelley-Godwin Archive, home of digitized manuscripts of Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, her father William Godwin, and her mother Mary Wollstonecraft. There, as we’ve previously featured on Open Culture, you can trace the evolution of Frankenstein by viewing all the extant pages of all its extant manuscripts. A full two centuries after its publication, Shelley’s novel continues to fascinate, and its central ideas and characters have become familiar to readers — and even non-readers — around the world. And in the view of Aldiss, Gibson, and many others besides, this story of a monster’s creation also brought to life a whole new cultural universe.

Related Content:

Mary Shelley’s Handwritten Manuscripts of Frankenstein Now Online for the First Time

Discovered: Lord Byron’s Copy of Frankenstein Signed by Mary Shelley

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply