The truth young idealistic lovers learn: relationships are messy and complicated—filled with disappointments, misunderstandings, betrayals great and small. They fall apart and sometimes cannot be put back together. It’s easy to grow cynical and bitter. Yet, as James Baldwin famously wrote, “you think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read.” You read, that is, the life stories and letters of writers and artists who have experienced outsized romantic bliss and torment, and who somehow became more passionately alive the more they suffered.

When it comes to personal suffering, Frida Kahlo’s biography offers more than one person could seem to bear. Already disabled by polio at a young age, she found her life forever changed at 18 when a bus accident sent an iron rod through her body, fracturing multiple bones, including three vertebrae, piercing her stomach and uterus. Recalling the old Gregorian hymn, Kahlo’s friend Mexican writer Andrés Henestrosa remarked that she “lived dying”—in near constant pain, enduring surgery after surgery and frequent hospitalizations.

In the midst of this pain, she found love with her mentor and husband Diego Rivera—and, it must be said, with many others. Kahlo, writes Alexxa Gotthardt at Artsy, “was a prolific lover: Her list of romances stretched across decades, continents, and sexes. She was said to have been intimately involved with, among others, Marxist theorist Leon Trotsky, dancer Josephine Baker, and photographer Nickolas Muray. However, it was her obsessive, abiding relationship with fellow painter Diego Rivera—for whom she’d harbored a passionate crush since she laid eyes on him at age 15—that affected Kahlo most powerfully.”

Her letters to Rivera—himself a prolific extra-marital lover—stretch “across the twenty-seven-year span of their relationship,” writes Maria Popova; they “bespeak the profound and abiding connection the two shared, brimming with the seething cauldron of emotion with which all fully inhabited love is filled: elation, anguish, devotion, desire, longing, joy.”

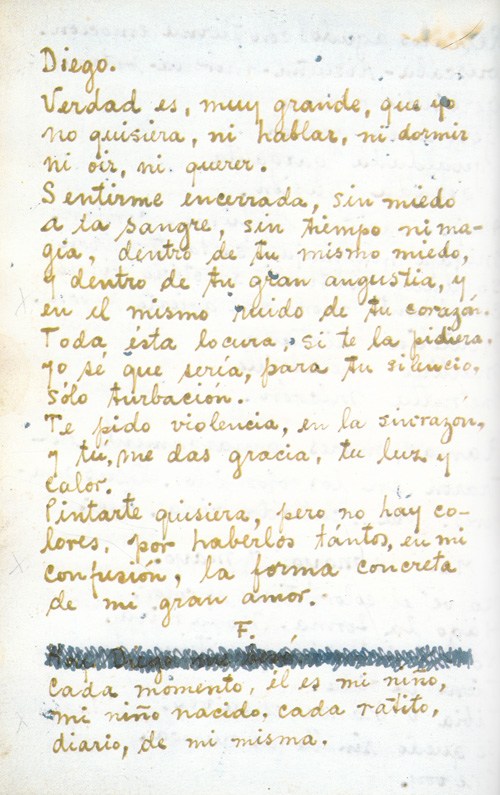

Diego.

Truth is, so great, that I wouldn’t like to speak, or sleep, or listen, or love. To feel myself trapped, with no fear of blood, outside time and magic, within your own fear, and your great anguish, and within the very beating of your heart. All this madness, if I asked it of you, I know, in your silence, there would be only confusion. I ask you for violence, in the nonsense, and you, you give me grace, your light and your warmth. I’d like to paint you, but there are no colors, because there are so many, in my confusion, the tangible form of my great love.

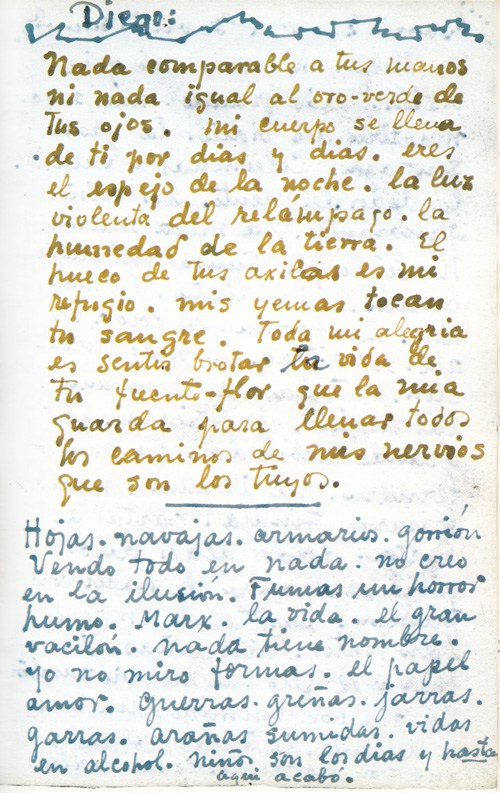

So begins the letter pictured at the top. In another, equally passionate and poetic letter, pictured further up, she writes:

Nothing compares to your hands, nothing like the green-gold of your eyes. My body is filled with you for days and days. you are the mirror of the night. the violent flash of lightning. the dampness of the earth. The hollow of your armpits is my shelter. my fingers touch your blood. All my joy is to feel life spring from your flower-fountain that mine keeps to fill all the paths of my nerves which are yours.

Kahlo and Rivera fell in love in 1928, when she asked him to look at her paintings. Over her mother’s objections, they married the following year. After ten tumultuous years, they divorced in 1939, then remarried in 1940 and stayed partnered until her death in 1954. Over these years, she poured out her emotions in letters, many, like those above, first written in her illustrated diary. Letters to and from her many lovers have also just emerged in a trove of personal artifacts, recently liberated from a bathroom at Casa Azul where they had been kept under lock and key at Rivera’s behest.

Both artists’ many affairs caused tremendous pain and “created rifts between them personally,” notes Katy Fallon at Broadly, although “their relationship has been mythologized past recognition,” in the way of so many other famous couples. In the most egregious betrayal, Rivera even slept with Kahlo’s younger sister Cristina, his favorite model, an act that inspired Frida’s 1937 painting Memory, the Heart, a self-portrait in which she stands with a metal rod piercing her chest, her hands seemingly amputated, face expressionless. We learn the wrong lessons from romanticizing “everything” about Frida and Diego’s life, Patti Smith suggests in her tribute to Kahlo’s love letters. But there is also danger in passing judgment.

“I don’t look at these two as models of behavior,” Smith says, but “the most important lesson… isn’t their indiscretions and love affairs but their devotion. Their identities were magnified by the other. They went through their ups and downs, parted, came back together, to the end of their lives.” In a 1935 letter to Rivera, read by pianist Mona Golabek above, Kahlo forgives his affairs, calling them “only flirtations…. At bottom, you and I love each other dearly, and thus go through adventures without numbers, beatings on doors, imprecations, insults, international claims. Yet, we will always love each other…. All the ranges I have gone through have served only to make me understand in the end that I love you more than my own skin.”

Read many more excerpts from Frida’s letters to Diego at Brain Pickings.

Related Content:

Artists Frida Kahlo & Diego Rivera Visit Leon Trotsky in Mexico: Vintage Footage from 1938

Rare Photos of Frida Kahlo, Age 13–23

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply