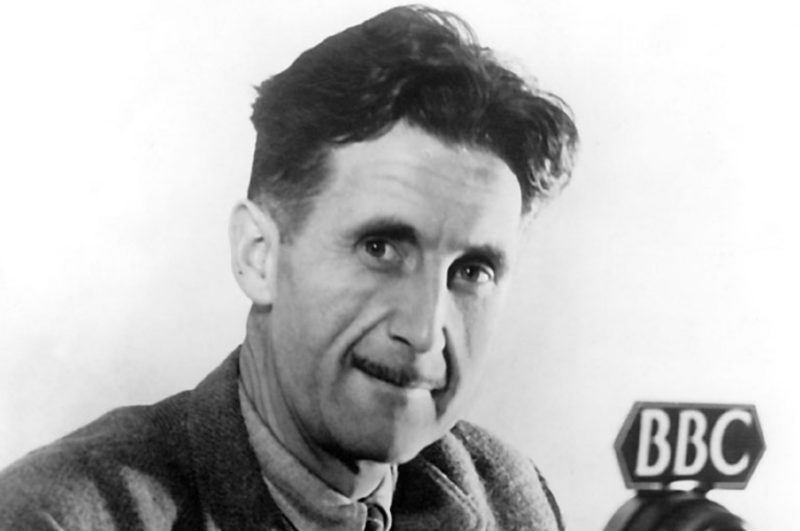

Image by BBC, via Wikimedia Commons

Tucked away in the style section of yesterday’s Washington Post—after the President of the United States basically declared allegiance to a hostile dictator, again, after issuing yet more denunciations of the U.S. press as “enemies of the people”—was an admonition from Margaret Sullivan to the “reality-based press.” “The job will require clarity and moral force,” writes Sullivan, “in ways we’re not always all that comfortable with.”

Many have exhausted themselves in asking, what makes it so hard for journalists to tell the truth with “clarity and moral force”? Answers range from the conspiratorial—journalists and editors are bought off or coerced—to the mundane: they normalize aberrant behavior in order to relieve cognitive dissonance and maintain a comfortable status quo. While the former explanation can’t be dismissed out of hand in the sense that most journalists ultimately work for media megaconglomerates with their own vested interests, the latter is just as often offered by critics like NYU’s Jay Rosen.

Established journalists “want things to be normal,” writes Rosen, which includes preserving access to high-level sources. The press maintains a pretense to objectivity and even-handedness, even when doing so avoids obvious truths about the mendacity of their subjects. Mainstream journalists place “protecting themselves against criticism,” Rosen wrote in 2016, “before serving their readers. This is troubling because that kind of self-protection has far less legitimacy than the duties of journalism, especially when the criticism itself is barely valid.”

As is far too often the case these days, the questions we grapple with now are the same that vexed George Orwell over fifty years ago in his many literary confrontations with totalitarianism in its varying forms. Orwell faced what he construed as a kind of censorship when he finished his satirical novel Animal Farm. The manuscript was rejected by four publishers, Orwell noted, in a preface intended to accompany the book called “The Freedom of the Press.” The preface was “not included in the first edition of the work,” the British Library points out, “and it remained undiscovered until 1971.”

“Only one of these” publishers “had any ideological motive,” writes Orwell. “Two had been publishing anti-Russian books for years, and the other had no noticeable political colour. One publisher actually started by accepting the book, but after making preliminary arrangements he decided to consult the Ministry of Information, who appear to have warned him, or at any rate strongly advised him, against publishing it.” While Orwell finds this development troubling, “the chief danger to freedom of thought and speech,” he writes, was not government censorship.

If publishers and editors exert themselves to keep certain topics out of print, it is not because they are frightened of prosecution but because they are frightened of public opinion. In this country intellectual cowardice is the worst enemy a writer or journalist has to face, and that fact does not seem to me to have had the discussion it deserves.

The “discomfort” of intellectual honesty, Orwell writes, meant that even during wartime, with the Ministry of Information’s often ham-fisted attempts at press censorship, “the sinister fact about literary censorship in England is that it is largely voluntary.” Self-censorship came down to matters of decorum, Orwell argues—or as we would put it today, “civility.” Obedience to “an orthodoxy” meant that while “it is not exactly forbidden to say this, that or the other… it is ‘not done’ to say it, just as in mid-Victorian times it was ‘not done’ to mention trousers in the presence of a lady. Anyone who challenges the prevailing orthodoxy finds himself silenced with surprising effectiveness,” not by government agents, but by a critical backlash aimed at preserving a sense of “normalcy” at all costs.

At stake for Orwell is no less than the fundamental liberal principle of free speech, in defense of which he invokes the famous quote from Voltaire as well as Rosa Luxembourg’s definition of freedom as “freedom for the other fellow.” “Liberty of speech and of the press,” he writes, does not demand “absolute liberty”—though he stops short of defining its limits. But it does demand the courage to tell uncomfortable truths, even such truths as are, perhaps, politically inexpedient or detrimental to the prospects of a lucrative career. “If liberty means anything at all,” Orwell concludes, “it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.”

Read his complete essay, “Freedom of the Press,” here.

via Brainpickings

Related Content:

George Orwell Reveals the Role & Responsibility of the Writer “In an Age of State Control”

George Orwell Creates a List of the Four Essential Reasons Writers Write

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him at @jdmagness

The issues which largely plagued George Orwell all those years ago have remained to a lesser or greater degree unaddressed. It is then perhaps unsurprising to find these same issues re-appearing again and again. Interesting food for thought indeed, Thank you for sharing open culture!