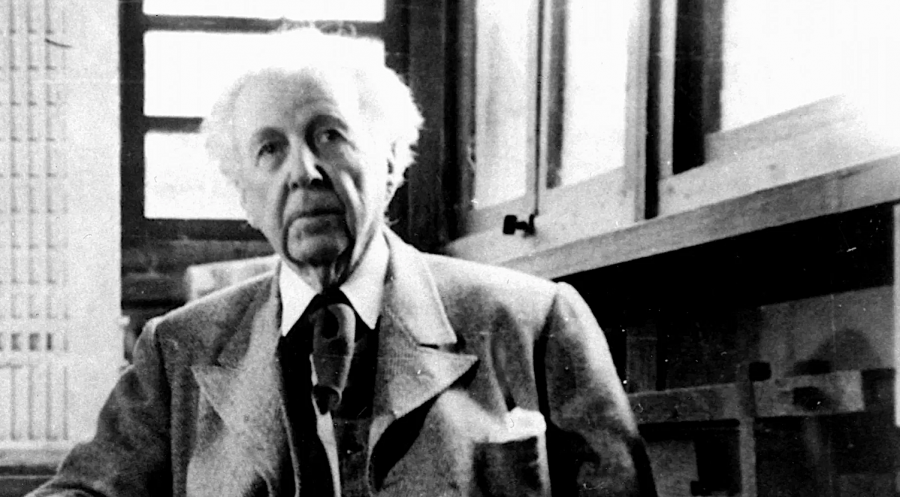

No figure looms larger over American architecture than Frank Lloyd Wright. From the early 1890s to the early 1920s he established himself as the builder of dozens of striking, stylistically innovative private homes as well as public works like Chicago’s Midway Gardens and Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel. But by the end of that period his personal life had already turned chaotic and even tragic, and in his professional life he saw his commissions dry up. Just when it looked like he might not leave much of a legacy at all, an idea came to him: why not start a school?

“Wright founded what he called the Taliesin Fellowship in 1932, when his own financial prospects were dismal, as they had been throughout much of the 1920s,” writes architecture critic Michael Kimmelman in the New York Review of Books. “Having seen the great Chicago architect Louis Sullivan, his former boss, die in poverty not many years earlier, Wright was forestalling his own prospective oblivion.” Charging a tuition of $675 (“raised to $1,100 in 1933, more than at Yale or Harvard”), Wright designed a program “to indoctrinate aspiring architects in his gospel of organic architecture, for which they would do hours of daily chores, plant crops, wash Wright’s laundry, and entertain him and his guests as well as one another in the evenings with musicals and amateur theatricals.”

There at Taliesin, his eponymous home-studio, located in the appropriately rural setting of Spring Green, Wisconsin, Wright sought to forge not just complete architects, and not just complete artists, but complete human beings. He proposed, in Kimmelman’s words, “the creation of a small, independent society made better through his architecture.” He also drew up a list, later included in his autobiography, of the qualities the builders of that society should possess:

I. An honest ego in a healthy body – good correlation

II. Love of truth and nature

III. Sincerity and courage

IV. Ability for action

V. The esthetic sense

VI. Appreciation of work as idea and idea as work

VII. Fertility of imagination

VIII. Capacity for faith and rebellion

IX. Disregard for commonplace (inorganic) elegance

X. Instinctive cooperation

This list reflects the kind of qualities Wright seemed to spend his life cultivating in himself, not to mention displaying to the public. Not that he showed much regard for the truth when it conflicted with his own mythmaking, nor an instinct for cooperation with those he considered less than his equals — and architecturally speaking, he didn’t consider anyone his equal. As well as Wright’s ego may have served him, not every artist needs one quite so colossal, but perhaps, per his list, they do need an honest one. “Early in life I had to choose between honest arrogance and hypocritical humility,” he once said. “I chose the former and have seen no reason to change.”

Related Content:

Frank Lloyd Wright Reflects on Creativity, Nature and Religion in Rare 1957 Audio

Haruki Murakami Lists the Three Essential Qualities For All Serious Novelists (And Runners)

John Cleese’s Advice to Young Artists: “Steal Anything You Think Is Really Good”

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

One can NEVER be finished speaking about FLW and his work. Living in Phoenix, I’ve had the chance to see his work first hand.

His statement as printed here certainly reflected his character — as he, indeed, felt he was a genius, and according to Edgar Tafel’s “From Apprentice to Genius” — FLW certainly was heard to mutter from time to time — that he was indeed a genius.

One of my favorite ripostes of his is when he was asked what he thought when he saw an ugly building, was that “It makes my teeth hurt!”

The world is poorer without characters like him.