Sigmund Freud died in 1939, and the nearly eight decades since haven’t been kind to his psychoanalytical theories, but in some sense he survives. “For many years, even as writers were discarding the more patently absurd elements of his theory — penis envy, or the death drive — they continued to pay homage to Freud’s unblinking insight into the human condition,” writes the New Yorker’s Louis Menand. He claims that Freud thus evolved, “in the popular imagination, from a scientist into a kind of poet of the mind. And the thing about poets is that they cannot be refuted. No one asks of ‘Paradise Lost’: But is it true? Freud and his concepts, now converted into metaphors, joined the legion of the undead.”

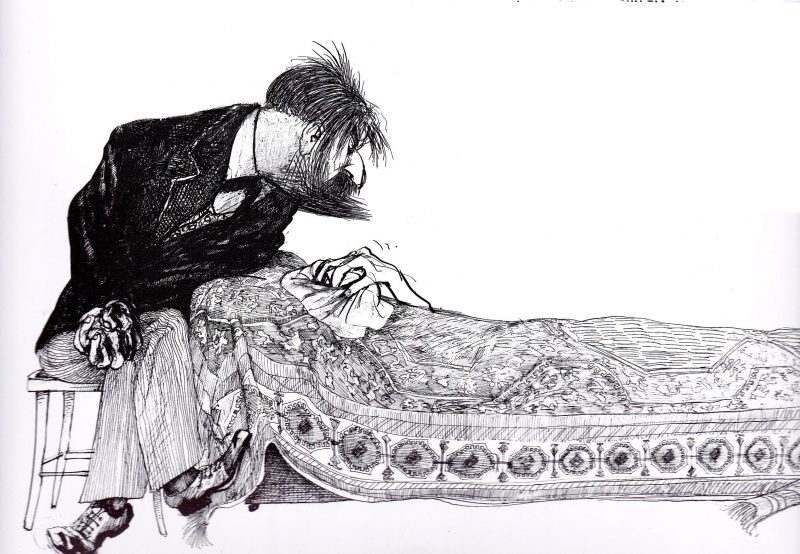

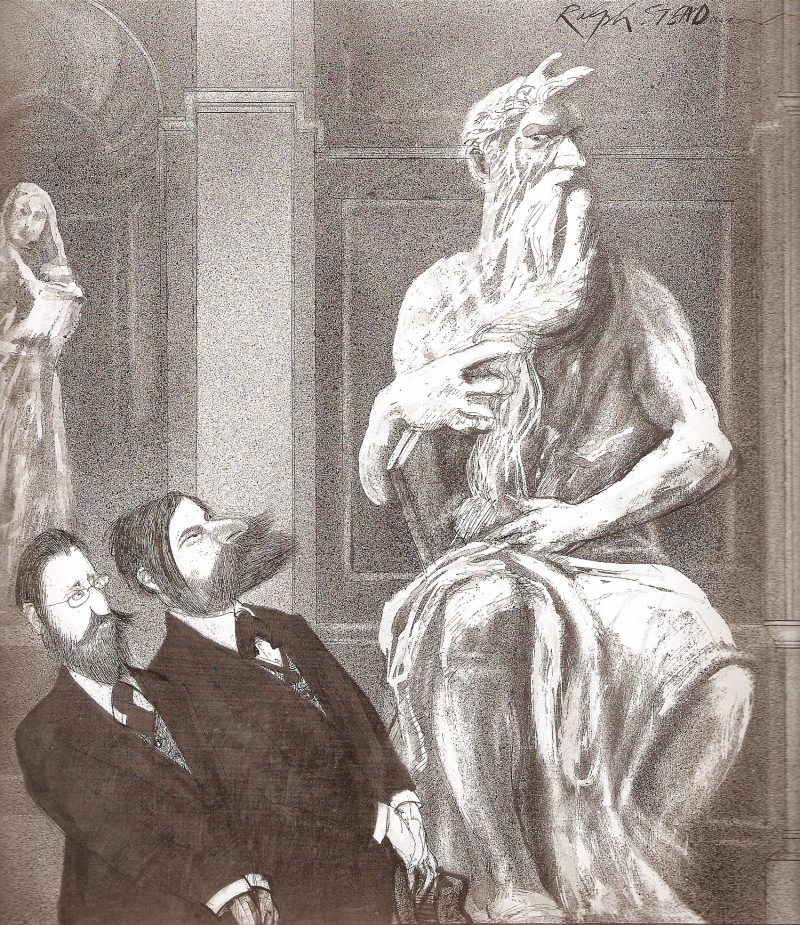

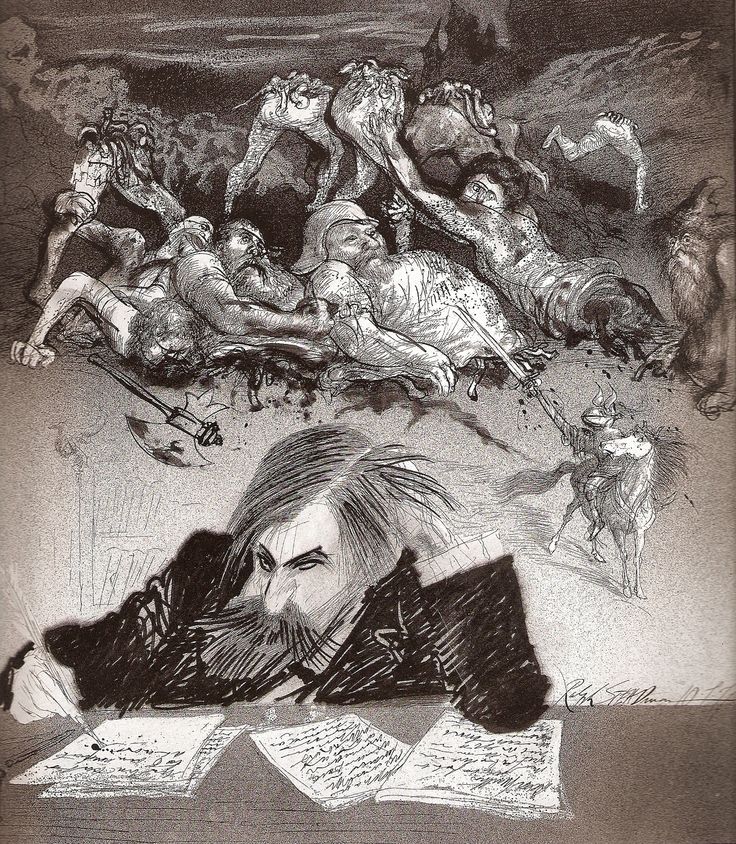

The master of a legion of undead psychological metaphors — who, in the ranks of living illustrators, could be more suited to render such a figure than Ralph Steadman? And how many of us know that he actually did so in 1979, when he produced an “art-biography” of the “Father of Psychoanalysis”?

Sigmund Freud, which has spent long stretches out of print since its first publication, tells the story of Freud’s life, beginning with his childhood in Austria to his death, not long after his emigration in flight from the Nazis, in London. It was there that he met Virginia Woolf, who in her diary describes him as “a screwed up shrunk very old man: with a monkey’s light eyes, paralyzed spasmodic movements, inarticulate: but alert.”

There, again, Freud sounds like one of Steadman’s drawings, sometimes outwardly unappealing but always possessed of an unignorable vitality generated by a solid core of perceptiveness. Earlier chapters of Freud’s life, characterized by intellectual as well as physical vigorousness aided by the 19th-century “miracle drug” of cocaine, also give the illustrator rich material to work with. One can’t help but think of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, which forged a permanent cultural link between Steadman’s art and Hunter S. Thompson’s prose. How “true” is the drug-fueled desert odyssey that book recounts? More so, perhaps, than many of Freud’s supposedly scientific discoveries. But as with the work of Freud, so with that of Thompson and Steadman: we return to it not because we want the truth, exactly, but because we can’t turn away from the often grotesque versions of ourselves it shows us.

You can pick up a copy of Steadman’s illustrated Sigmund Freud here.

Related Content:

Sigmund Freud, Father of Psychoanalysis, Introduced in a Monty Python-Style Animation

How a Young Sigmund Freud Researched & Got Addicted to Cocaine, the New “Miracle Drug,” in 1894

Ralph Steadman’s Wildly Illustrated Biography of Leonardo da Vinci (1983)

Gonzo Illustrator Ralph Steadman Draws the American Presidents, from Nixon to Trump

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply