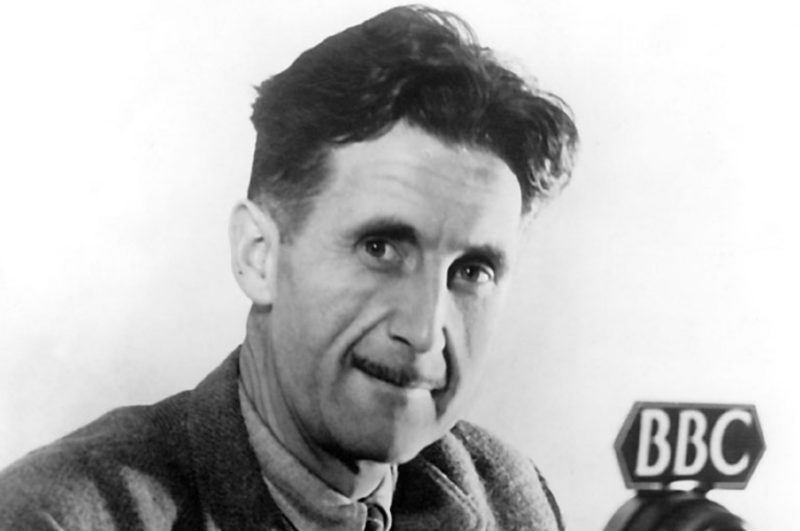

Image by BBC, via Wikimedia Commons

What is the role of the writer in times of political turmoil? Professional athletes get told to “shut up and play” when they speak out—as if they had no vested interest in current events or a constitutional right to speak. But it is generally assumed that writers have a central part to play in public discourse, even when they don’t explicitly write about politics. When writers make controversial statements, it sounds a little ridiculous to tell them to “shut up and write.”

On one view, “it is the responsibility of intellectuals to speak the truth and to expose lies,” as Noam Chomsky declares in “The Responsibility of Intellectuals.” Chomsky deplores those who comfortably accept the consensus and deliberately disseminate untruths out of a “failure of skepticism” and blind belief in the purity of their motives. Faced with obvious lies, outrages, and oppression, “intellectuals”— journalists, academics, artists, even clergy—should “follow the path of integrity, wherever it may lead.”

One such intellectual, George Orwell, is often held up across the political spectrum as a paradigm of intellectual integrity. Orwell, as you might expect, had his own thoughts on what he called “the position of the writer in an age of State control.” He expressed his view in a 1948 essay titled “Writers and the Leviathan.” He accords with Chomsky in most respects, yet in the end does not endorse the view that the political responsibilities of writers are greater than anyone else. Yet Orwell also expresses similar wariness about writers becoming cardboard propagandists, and losing their creative, critical, and ethical integrity.

Orwell begins his argument by claiming that writers bear some responsibility for creating the culture that nurtures politics. “WHAT KIND of State rules over us,” he writes, “must depend partly on the prevailing intellectual atmosphere: meaning, in this context, partly on the attitude of writers and artists themselves.” Moreover, he suggests, it is unrealistic to expect writers, or anyone for that matter, not to have strong political opinions. The “special problem of totalitarianism” infects everything, even literature, making “a purely aesthetic attitude,” like that of Oscar Wilde, “impossible.”

This is a political age. War, Fascism, concentration camps, rubber truncheons, atomic bombs, etc are what we daily think about, and therefore to a great extent what we write about, even when we do not name them openly. We cannot help this. When you are on a sinking ship,

your thoughts will be about sinking ships.

Seventy years after Orwell’s essay, we live in no less a “political age,” burdened by daily thoughts of all the above, plus the deadly effects of climate change and other ills Orwell could not foresee.

We also see our age reflected in Orwell’s description of the “orthodoxies and ‘party lines’” that plague the writer. “A modern literary intellectual,” he writes, “lives and writes in constant dread—not, indeed, of public opinion in the wider sense, but of public opinion within his own group…. At any given moment there is a dominant orthodoxy, to offend against which needs a thick skin and sometimes means cutting one’s income in half for years on end.”

But integrity requires unorthodox thinking. Orwell goes on to analyze a number of “unresolved contradictions” on the left that make a wholesale, uncritical embrace of its political orthodoxy tantamount to “mental dishonesty.” He takes pains to note that this phenomenon is inherent to every political ideology: “acceptance of ANY political discipline seems to be incompatible with literary integrity.” Here is a dilemma. Ignoring politics is irresponsible and impossible. But so is committing to a party line.

Well, then what? Do we have to conclude that it is the duty of every writer to “keep out of politics”? Certainly not! In any case, as I have said already, no thinking person can or does genuinely keep out of politics, in an age like the present one. I only suggest that we should

draw a sharper distinction than we do at present between our political and our literary loyalties, and should recognise that a willingness to DO certain distasteful but necessary things does not carry with it any obligation to swallow the beliefs that usually go with them. When a writer engages in politics he should do so as a citizen, as a human being, but not AS A WRITER. I do not think that he has the right, merely on the score of his sensibilities, to shirk the ordinary dirty work of politics. Just as much as anyone else, he should be prepared to deliver lectures in draughty halls, to chalk pavements, to canvass voters, to distribute leaflets, even to fight in civil wars if it seems necessary. But whatever else he does in the service of his party, he should never write for it. He should make it clear that his writing is a thing apart. And he should be able to act co-operatively while, if he chooses, completely rejecting the official ideology. He should never turn back from a train of thought because it may lead to a heresy, and he should not mind very much if his unorthodoxy is smelt out, as it probably will be.

It might be objected that Orwell himself wrote an awful lot about politics from a definite point of view (which he defined in “Why I Write” as “against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism”). He even cited “political purpose” as one of four reasons that serious writers have for writing. But before accusing him of hypocrisy, we must read on for more nuance. “There is no reason,” he says, that a writer “should not write in the most crudely political way, if he wishes to. Only he should do so as an individual, an outsider, at the most an unwelcome guerilla on the flank of a regular army.” (His position is reminiscent of James Baldwin’s, a political writer who “excoriated the protest novel.”) And if the writer finds some of that army’s positions untenable, “then the remedy is not to falsify one’s impulses, but to remain silent.”

Orwell’s essay characterizes the “almost inevitable nature of the irruption of politics into culture,” argues Enzo Traverso, “Writers were no longer able to shut themselves up in a universe of aesthetic values, sheltered from the conflicts that were tearing apart the old world.” The kind of compartmentalization he recommends might seem cynical, but it represents for him a pragmatic third way between the “ivory tower” and the “party machine,” a way for the writer to act ethically in the world yet retain a “saner self [who] stands aside, records the things that are done and admits their necessity, but refuses to be deceived as to their true nature” and thus become a party mouthpiece, rather than an artist and critical thinker.

Related Content:

George Orwell Creates a List of the Four Essential Reasons Writers Write

George Orwell Explains in a Revealing 1944 Letter Why He’d Write 1984

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

I think the issue is that many (perhaps most?) people instinctually reject the idea that politics have to be injected into every facet of life. After all, most of life is lived on the micro, not the macro, level. That is why many people — and I would have to include myself here — would prefer athletes, musicians, novelists, CEOs, etc. to just “shut up” and do what people are paying them to do (not to mention that they often sound inane when they venture out of their domains of expertise).

Be expert or remain silent? One is worthy of consideration only in the narrow realm within which one is remunerated? What a dreary static hell for a human person to desire to dwell