How to make a name for oneself in the art world? Every up-and-coming artist has to face that intimidating question in one way or another, but Robert Rauschenberg, now remembered as a leading light of the pop art movement, came up with a particularly memorable answer. When in 1953 he got the counterintuitive idea to make a drawing not by drawing, but by erasing, he at first tried erasing images he’d drawn himself. This brought him to the realization that not only should his erasing constitute more than half the process — “I wanted it to be the whole,” he later said — but that, to make a real artistic impact, he’d have to erase the work of someone important.

The logical choice at the time: Willem de Kooning, then already considered a master of abstract expressionism. “I bought a bottle of Jack Daniels and went up and knocked on his door, praying the whole time that he wouldn’t be home,” says Rauschenberg in the interview clip above, “but he was home.” Eventually he sold the older and more eminent artist on the idea of taking a drawing, erasing it, and turning that into art of his own, a pitch no doubt assisted by Rauschenberg and de Kooning’s already friendly relationship. (The already vast difference between their artistic styles also took the notion of artistic patricide out of the question.)

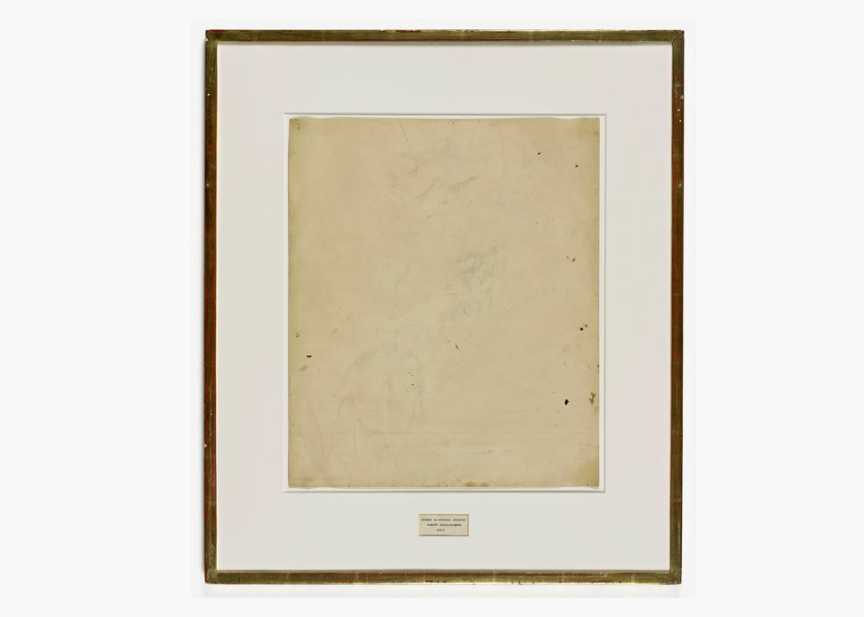

De Kooning at first resisted, but then doubled down: “I want it to be something I’ll miss,” Rauschenberg remembers him saying before picking out the sacrifice. Erased de Kooning Drawing, the result of two months of erasing and countless spent erasers, “essentially remained an underground, art world phenomenon for more than ten years after it was completed.” So writes SFMOMA curator Sarah Roberts in an essay on the piece. “Significantly, it was excluded from numerous important solo and group exhibitions in the late 1950s and early 1960s, crucial years when Rauschenberg’s reputation was becoming established internationally.”

But slowly, over the years, word spread through the art media and social scenes, and now the 27-year-old Rauschenberg’s brazen artistic act has a place among the progenitors of conceptual art. “Yes, the erasure was an act of destruction,” writes Roberts, “but as a creative gesture it was also an act of reverence or even devotion—to de Kooning, to drawing, to art history, and to the idea of taking a risk and being open to whatever comes as a result.” Though practically unknown for quite a long time, Erased de Kooning Drawing can now hardly be forgotten — which takes erasing a respected forebear’s work off the table as a means of name-making for young artists today, each of whom will have to find their own way to set off a slow-burn shock.

Related Content:

Robert Rauschenberg’s 34 Illustrations of Dante’s Inferno (1958–60)

The MoMA Teaches You How to Paint Like Pollock, Rothko, de Kooning & Other Abstract Painters

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

“…find their own way to set off a slow-burn shock.”

Does there have to be a shock?

Context: shock can be a side effect of doing something new. Often however, it becomes an end in itself: what can I do that will shock? And at it’s very worst, it seems little more than the focal point of marketing. Shock sells. Shock is easy to understand. Shock is wildness tamed. Shock is blowing away Palestinians with a sniper rifle with zero consequences forever