When will the world end?

We can find serious scientific answers to this question, depending on what we mean by “world” and “end.” If civilization as we currently know it, climate scientists’ worst-case scenario points toward somewhere around 2100 as the beginning of the end. (New York magazine points out that it “probably won’t kill all of us”). It’s possible, but not inevitable.

If we mean the end of all life on earth, the forecast looks quite a bit rosier: we’ve probably got about a billion years, writes astrophysicist Jillian Scudder, before the sun becomes “hot enough to boil our oceans.” Still not a cheerful thought, but perhaps many more creatures will take after the tardigrade by then. That’s not even to mention nuclear war or the epidemics, zombie and otherwise, that could take us out.

But of course, for a not inconsiderable number of people—including a few currently occupying key positions of power in the U.S.—the question of the world’s end has nothing to do with science at all but with eschatology, that branch of theological thought concerned with the Apocalypse.

Theological thinkers have written about the Apocalypse for hundreds of years, and the world’s end was frequently perceived as just around the corner for many of the same reasons modern secular people feel apocalyptic dread: disease, natural disasters, wars, rumors of wars, imperial power struggles, uncomfortably shifting demographics….

Take 15th-century Europe, when “the Apocalypse weighed heavily on the minds of the people,” as Betsy Mason and Greg Miller write at the National Geographic blog All Over the Map: “Plagues were rampant. The once-great capital of the Roman empire, Constantinople, had fallen to the Turks. Surely, the end was nigh.”

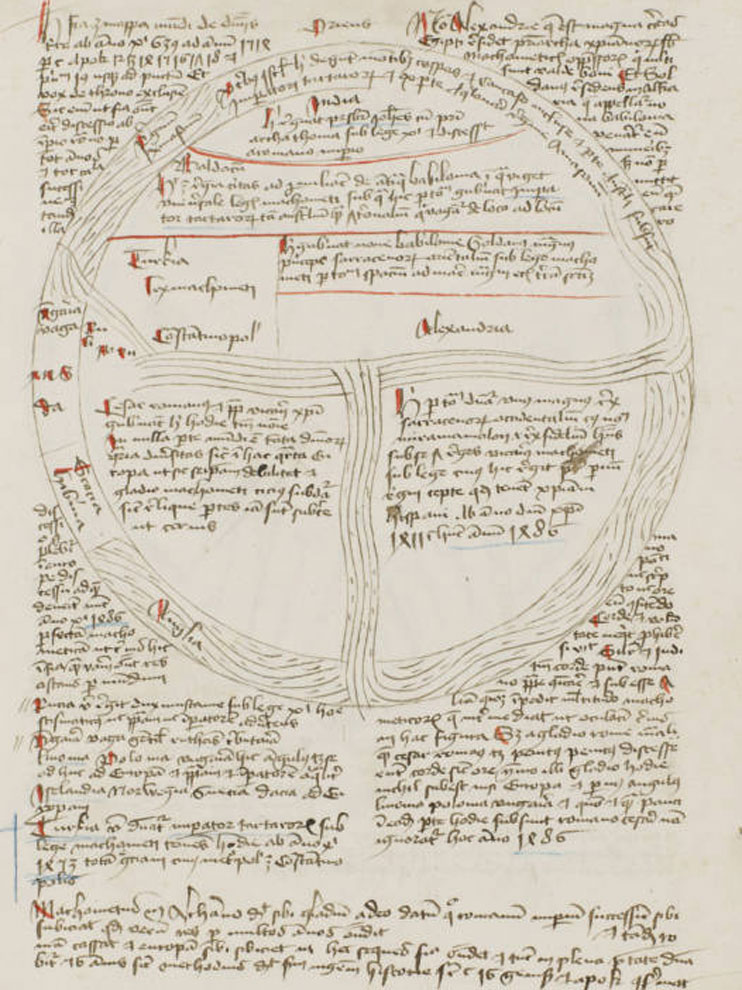

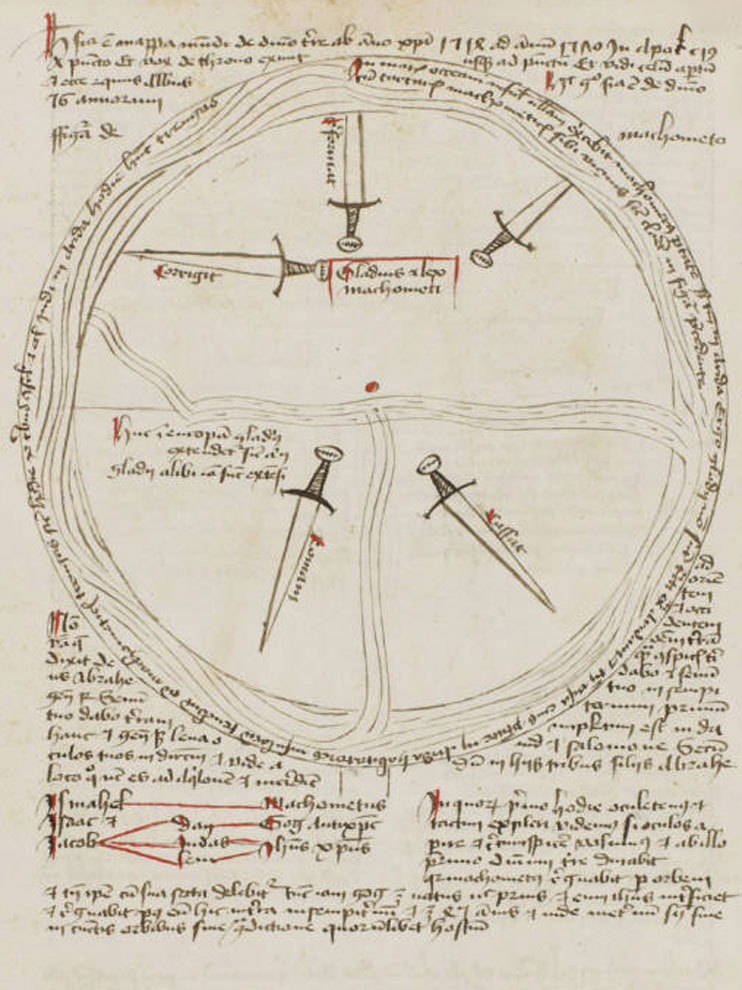

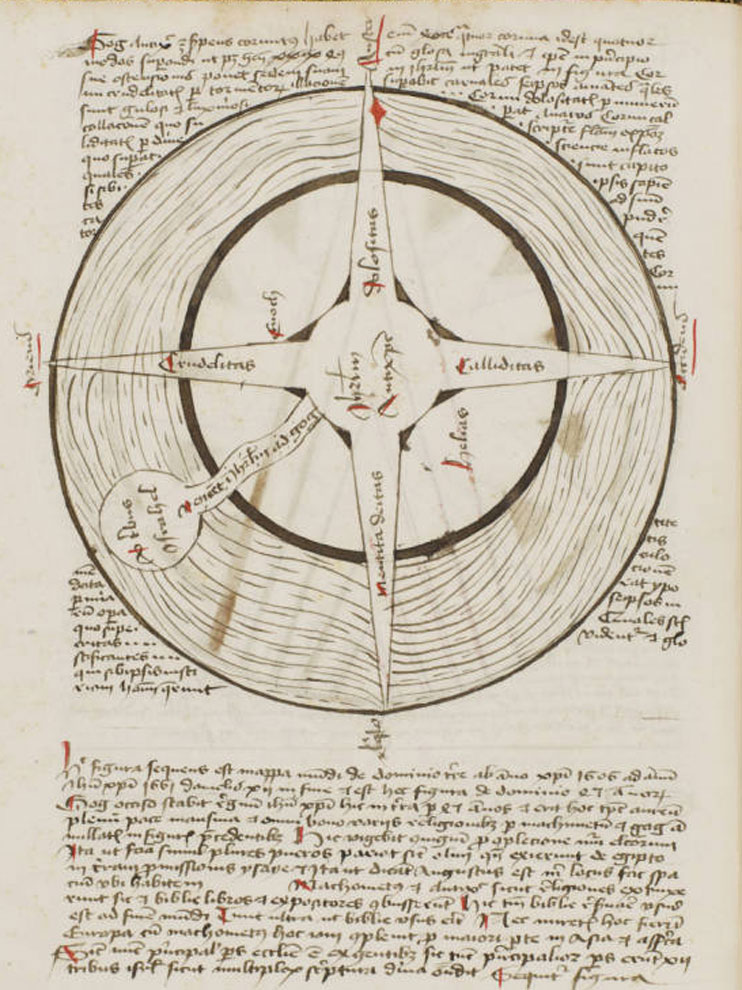

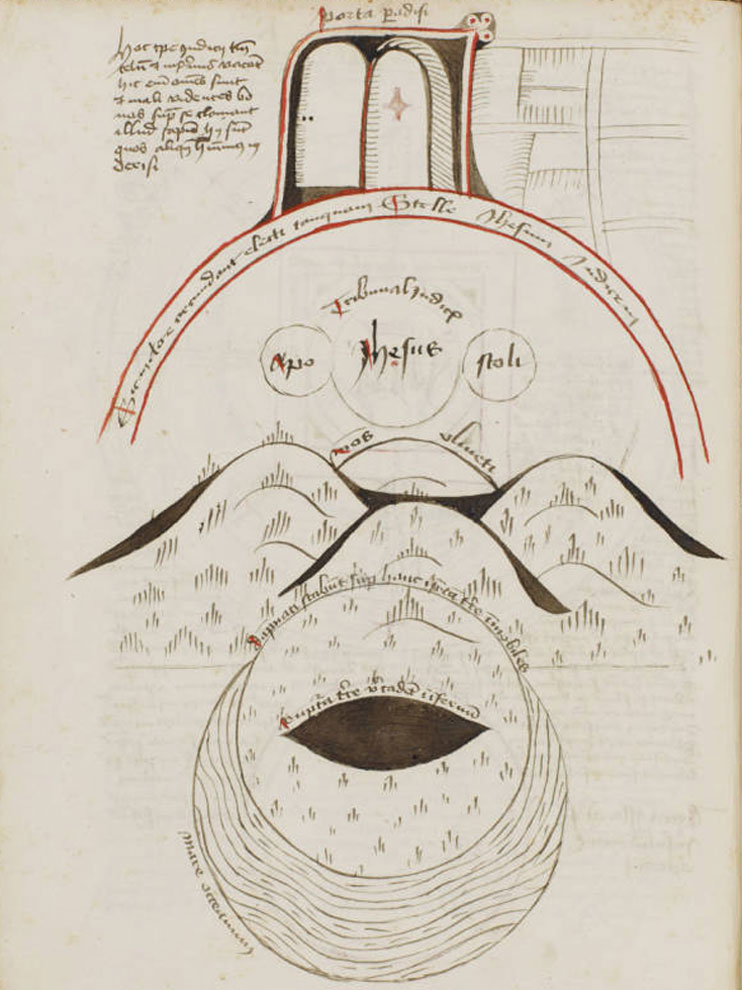

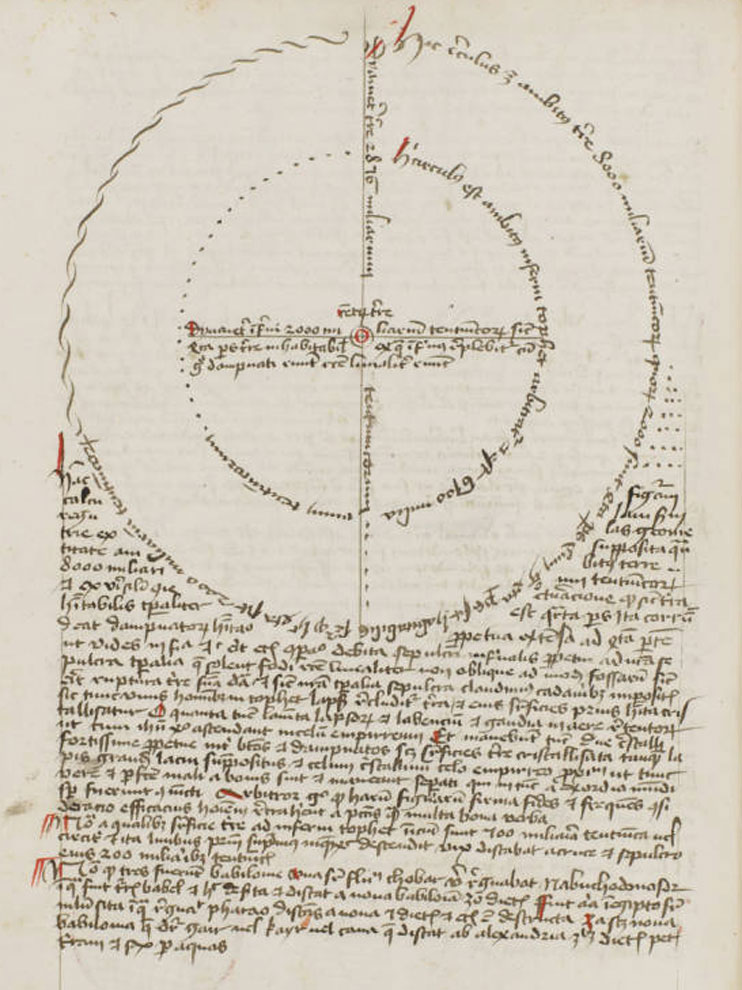

While a niche publishing market in the nascent print era produced “dozens of printed works” describing the “coming reckoning in gory detail… one long-forgotten manuscript depicts the Apocalypse in a very different way—through maps.” As you can see here, these maps convey the unfolding of worse-to-worser scenarios in a number of visual registers: temporal, symbolic, geographic, thematic, etc.

At the top, the nested triangles depict the rise of the Antichrist between the years 1570 and 1600. The central concern for this author was the supposed global threat of Islam. Thus, the next map, its “T” shape a common Medieval world map device, shows the world before the Apocalypse, the text around it explaining that “Islam is on the rise from 639 to 1514.”

Then, we have a circular map with five swords pointing at the edges of the known world, illustrating the author’s contention that Islamic armies would reach the edges of the earth. The other maps depict the “four horns of the Antichrist,” above, Judgement Day, below, (the black eye at the bottom is the “black abyss that leads to hell”), and, further down, a diagram describing “the relative diameters of Earth and Hell.”

Made in Lübeck, Germany sometime between 1486 and 1488, the manuscript is written in Latin, “but it’s not as scholarly as other contemporary manuscripts,” write Mason and Miller, “and the penmanship is fairly poor.” Historian of cartography Chet Van Duzer explains that “it’s aimed at the cultural elite, but not the pinnacle of the cultural elite.”

Pointing out the obvious, Van Duzer says, “there’s no way to escape it, this work is very anti-Islamic,” a widespread sentiment in medieval Europe, when the “clash of civilizations” narrative spread its roots deep in certain strains of Western thinking. This particular text also “includes a section on astrological medicine and a treatise on geography that’s remarkably ahead of its time.”

Van Duzer and Ilya Dines have studied the rare manuscript for its insightful passages on geography and cartography and published their research in a book titled Apocalyptic Cartography. For all its theological alarmism, the manuscript is surprisingly thoughtful when it comes to analyzing its own formal properties and perspectives.

Mason and Miller note that “the author outlines an essentially modern understanding of thematic maps as a means to illustrate characteristics of the people or political organization of different regions.” As Van Duzer puts it, “this is one of the most amazing passages, to have someone from the 15th century telling you their ideas about what maps can do.” This marks the work, he claims in the introduction to Apocalyptic Cartography, as that “of one of the most original cartographers of the period.”

The Apocalypse Map now resides at the Huntington Library in Los Angeles.

Related Content:

In 1704, Isaac Newton Predicts the World Will End in 2060

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

This article contains some odd assumptions. It was not completely foolish for Christendom to fear the Islamic world at that time (and vice versa, no doubt). Both faiths were militant and liable to overrun the territories of the other. Islam had a long history of subsuming huge areas of Christian Asia and Europe under the sword. To suggest that the threat from Islam was imaginary and comparable to the overblown Islamist fears of the contemporary world is rather silly. In fact the greatest Islamic incursions into the heart of Europe were still to come. Forcing the past to conform to the narrative of the present is fraught with danger.