Teaching child visitors how to write their names using an unfamiliar or antique alphabet is a favorite activity of museum educators, but Dr. Irving Finkel, a cuneiform expert who specializes in ancient Mesopotamian medicine and magic, has grander designs.

His employer, the British Museum, has over 130,000 tablets spanning Mesopotamia’s Early Dynastic period to the Neo-Babylonian Empire “just waiting for young scholars to come devote themselves to (the) monkish work” of deciphering them.

Writing one’s name might well prove to be a gateway, and Dr. Finkel has a vested interest in lining up some new recruits.

The museum’s Department of the Middle East has an open access policy, with a study room where researchers can get up close and personal with a vast collection of cuneiform tablets from Mesopotamia and surrounding regions.

But let’s not put the ox before the cart.

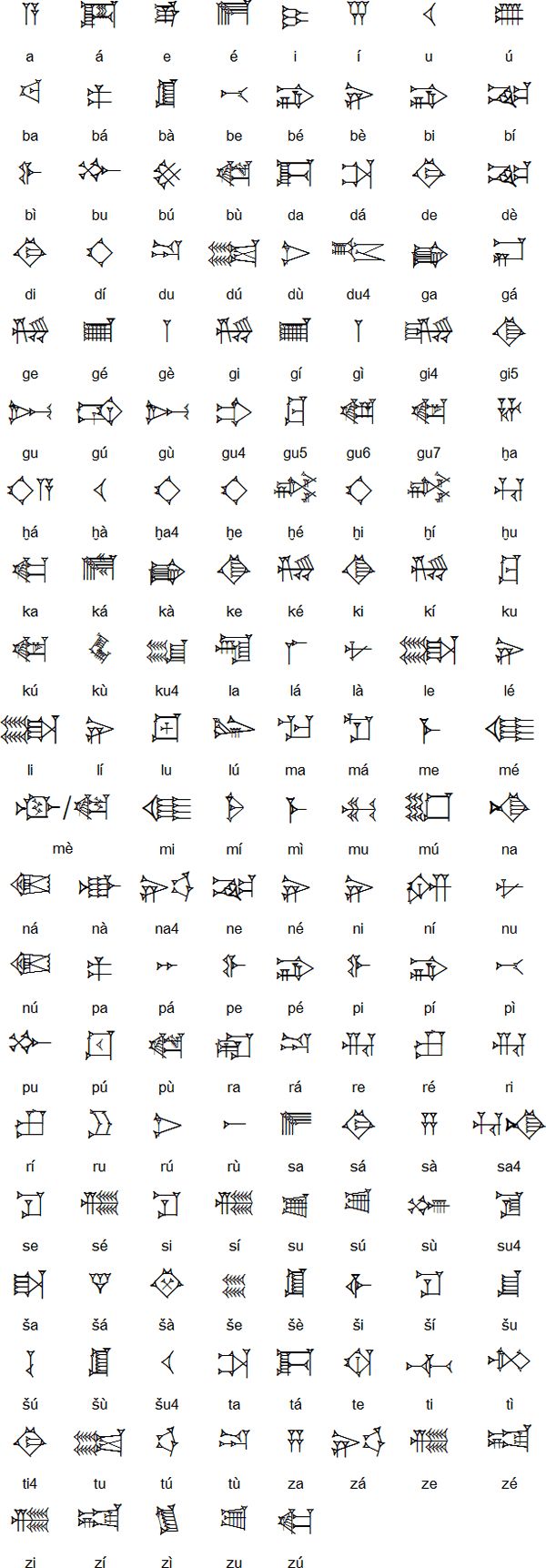

As the extremely personable Dr. Finkel shows Matt Gray and Tom Scott of Matt and Tom’s Park Bench, above, cuneiform consists of three components—upright, horizontal and diagonal—made by pressing the edge of a reed stylus, or popsicle stick if you prefer, into a clay tablet.

The mechanical process seems fairly easy to get the hang of, but mastering the oldest writing system in the world will take you around six years of dedicated study. Like Japan’s kanji alphabet, the oldest writing system in the world is syllabic. Properly written out, these syllables join up into a flowing calligraphy that your average, educated Babylonian would be able to read at a glance.

Even if you have no plans to rustle up a popsicle stick and some Play-Doh, it’s worth sticking with the video to the end to hear Dr. Finkel tell how a chance encounter with some naturally occurring cuneiform inspired him to write a horror novel, which is now available for purchase, following a successful Kickstarter campaign.

Begin your cuneiform studies with Irving Finkel’s Cuneiform: Ancient Scripts.

via Mental Floss

Related Content:

You Could Soon Be Able to Text with 2,000 Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs

Hear The Epic of Gilgamesh Read in its Original Ancient Language, Akkadian

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Her solo show Nurse!, in which one of Shakespeare’s best loved female characters hits the lecture circuit to set the record straight premieres in June at The Tank in New York City. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Devout Open Culture reader in Japan here.

I feel compelled to point out that Japanese kanji are not syllabic, as it says in the article on cuneiform. Theyre ideographic. The syllabic ones are kana (hiragana and katakana).

I am extremely grateful for the site, and it is precisely because I consider it just as worthy and rigorous as, say, the New Yorker that I feel the need to point this out.

Thank you!

Colin Smith, I’m afraid you are incorrect in your assertion that Japanese Kanji are not syllabic. You are correct when you state that the kana are syllabic, but all Japanese Kanji, and every Japanese reading of every Japanese kanji, are always pronounced consistent with the Japanese syllabic system. Although almost all of the currently commonly used Japanese Kanji are considered by some to be used ideographically, many Japanese words are written with specific kanji based on that kanji’s pronunciation and not on it’s meaning. But no matter which way they are used in any given context, the reading (pronunciation) is always syllabic.

Thank you

could you add how to write, “school projects are fun!”, ?

I cannot find a key for pronunciation of the phonemes in the graphic image. Is there such a thing?

Numa Fernando Solano

bye bye.

Fascinating, Thankyou!