If there were ever an exhibition of artistic “one-hit-wonders,” surely Edvard Munch’s The Scream would occupy a central place, maybe hung adjacent to Grant Wood’s American Gothic. The ratio of those who know this single painting to those who know the artist’s other works must be exponentially high, which is something of a shame. That’s not to say The Scream does not deserve its exalted place in popular culture—like Wood’s stone-faced Midwest farmers, the wavy figure, clutching its screaming skull-like head, resonates at the deepest of psychic frequencies, an archetypal evocation of existential horror.

Not for nothing has Sue Prideaux subtitled her Munch biography Behind the Scream. “Rarely in the canon of Western art,” writes Tom Rosenthal at The Independent, “has there been so much anxiety, fear and deep psychological pain in one artist. That he lived to be 80 and spent only one period in an asylum is a tribute not only to Munch’s physical stamina but to his iron will and his innate, robust psychological strength.” Born in Norway in 1863, the sickly Edvard, whose mother died soon after his birth, was raised by a harsh disciplinarian father who read Poe and Dostoevsky to his children and, in addition to beating them “for minor infractions,” would “invoke the image of their blessed mother who saw them from heaven and grieved over their misbehavior.”

The trauma was compounded by the death of Munch’s sister and, later, his brother, and by the institutionalization of another sister, Laura, diagnosed with schizophrenia. Munch’s own childhood illness made his schooling erratic, though he did manage to receive some artistic training, briefly, at Oslo’s Art Association, an artist’s club where he “learnt by copying the works on display.”

From there the young Munch launched himself into an extraordinarily productive career, punctuated by legendary bouts of drinking and carousing and intense friendships with literary figures like August Strindberg.

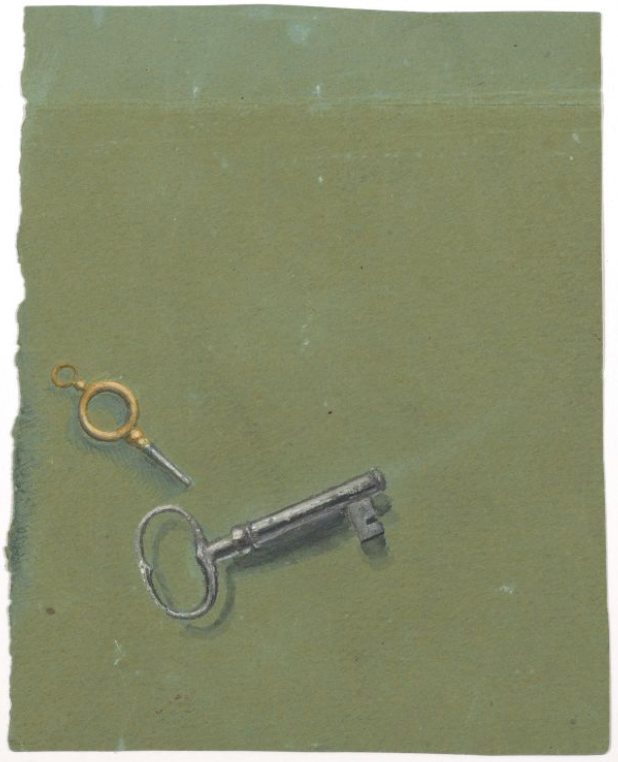

If we count ourselves among those who know little of Munch’s work, a new initiative from the Munch Museum in Oslo aims to correct that by making over 7,600 of Munch’s drawings available online. “The online catalog, free to all,” notes Hyperallergic’s Sarah Rose Sharp, “represents a tremendous feat of logistics, and features drawings that go back as far as the artist’s childhood, sketchbooks, studies of tools, coins, and keys that demonstrate Munch’s dedication as a disciplined draftsman, and watercolors of buildings that were some of the first bodies of work developed by the artist in his youth.”

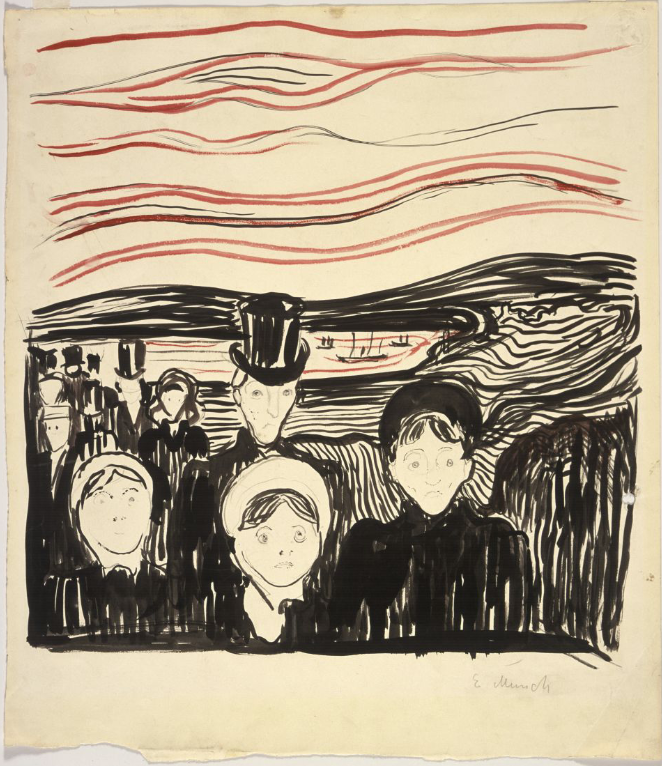

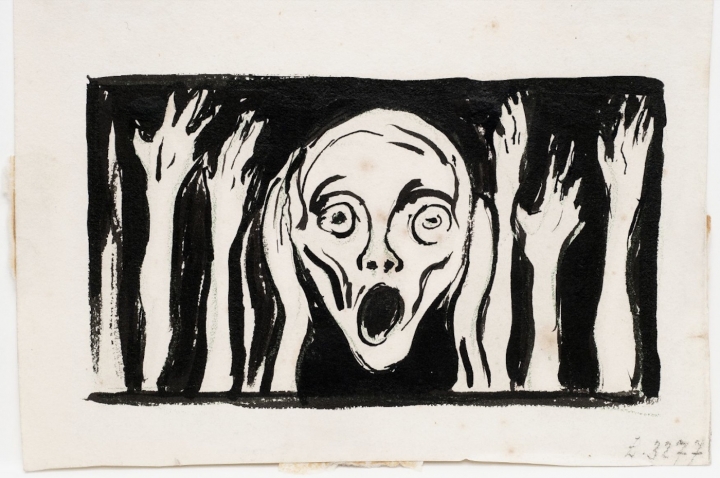

Over 90% of the drawings on digital display come from the Museum’s holdings, the rest from other public and private collections. “The goal is to make Munch’s art known and easily accessible to as many people as possible,” Magne Bruteig, Senior Curator for Prints and Drawings, tells Hyperallergic. “Since the majority of the drawings had never been exhibited or published in any way, it has been of special importance to reveal this ‘hidden treasure.’” The online collection, then, not only serves as an introduction for Munch novices but also for longtime admirers of the artist’s work, who have hitherto had little to no access to this huge collection of studies, preparatory sketches, watercolors, etc., which includes the miserable family grouping of Angst, at the top, the reprise of his infamous Scream figure, further up, from 1898, and The Sick Child, above, a portrait of his sister Sophie who died in childhood.

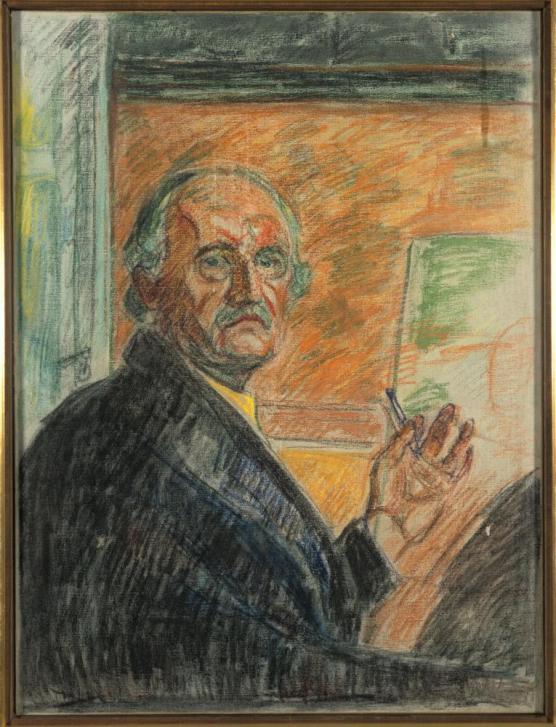

The drawings date back to 1873, when Munch was only ten years old and inserted a series of his own illustrations into a copy of Grimm’s Fairytales. The final works date from 1943, the year before the artist’s death, when he made the self-portrait above in pastel crayon. Munch’s work, writes Rosenthal, “is compulsively autobiographical.” Remaining a committed bachelor all of his life, he said that “his paintings were his children, even though he gave many of them a somewhat Spartan upbringing, deliberately leaving them not only unvarnished but exposed to the elements in his vast outdoor studio or hung on walls, unframed and with nails through them.” The several thousand drawings he fathered seem to have been treated with more care. Delve into the enormous collection at the Oslo Munch Museum site here, where you can also view many of the artist’s paintings and learn much more about his life and work through articles and essays.

Related Content:

30,000 Works of Art by Edvard Munch & Other Artists Put Online by Norway’s National Museum of Art

Edvard Munch’s Famous Painting “The Scream” Animated to the Sound of Pink Floyd’s Primal Music

The Edvard Munch Scream Action Figure

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

I would never characterize Munch as a one hit wonder. He’s an extremely well known painter, and his ouevre is not at all obscure.

who said that he was?

The first paragraph explicitly says so…

I understand. I only used the phrase to point out that millions of people know The Scream (from t‑shirts, mousepads, posters, The Simpsons etc.) but know nothing about Munch. He’s obscure to a large number of people who are very familiar with one painting.

.… tis true that the first paragraph patronises many of us reading this — who will all know his works beyond the scream very well and have for decades since 1940s etc — and perhaps undermines the man himself. Otherwise a fair article and link to a trove of qualia !

I think Munch was not as complex as those who would have us believe so,…more so a product of his time and exposure. I think his learned traits were reflected in his work and he was deeply concerned with momentary emotion. Shocking others as well as himself appears to be a delight he revelled in, although the essence of feelings compelled him to say here it is. Thank you Edvard for your honesty and desire to unveil life.