Two years ago, we highlighted collector David Rumsey’s huge map archive, which he donated to Stanford University in April of 2016 and which now resides at Stanford’s David Rumsey Map Center. The opening of this physical collection was a pretty big deal, but the digital collection has been on the web, in some part, and available to the online public since 1996. Twenty years ago, however, though the internet was decidedly becoming an everyday feature of modern life, it was difficult for the average person to imagine the degree to which digital technology would completely overtake our lives, not to mention the almost unbelievable wealth and power tech companies would amass in such short time.

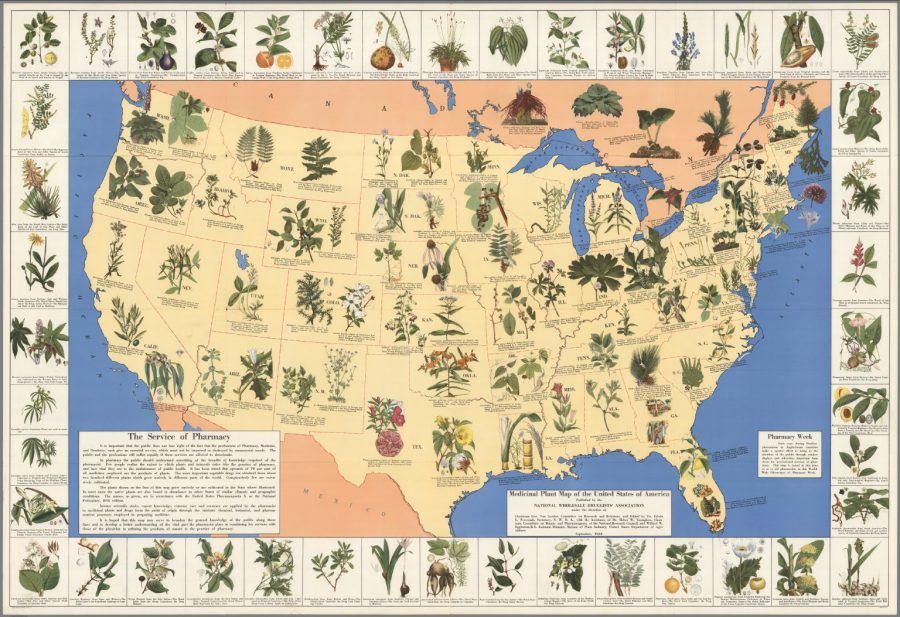

Similarly, when the above 1932 Medicinal Plant Map of the United States (see in a larger format here) first appeared—one of the tens of thousands of maps available in the digital Rumsey collection—few people other than Aldous Huxley could have foreseen the exponential advances, and the rise of wealth and power, to come in the pharmaceutical industry.

But the pharmacists had a clue. The map, produced by the National Wholesale Druggists’ Association, “was intended to boost the image of the profession,” writes Rebecca Onion at Slate, “at a time when companies were increasingly compounding new pharmaceuticals in labs,” thereby rendering much of the drug-making knowledge and skill of old-time druggists obsolete.

Although the commercial pharmaceutical industry began taking shape in the late 19th century, it didn’t fully come into its own until the so-called “golden era” of 1930–1960, when, says Onion, researchers developed “a flood of new antibiotics, psychotropics, antihistamines, and vaccines, increasingly relying on synthetic chemistry to do so.” Over-the-counter medications proliferated, and pharmacists became alarmed. They sought to persuade the public of their continued relevance by pointing out, as a short blurb at the bottom left corner of the map notes, that “few people realize the extent to which plants and minerals enter into the practice of pharmacy.”

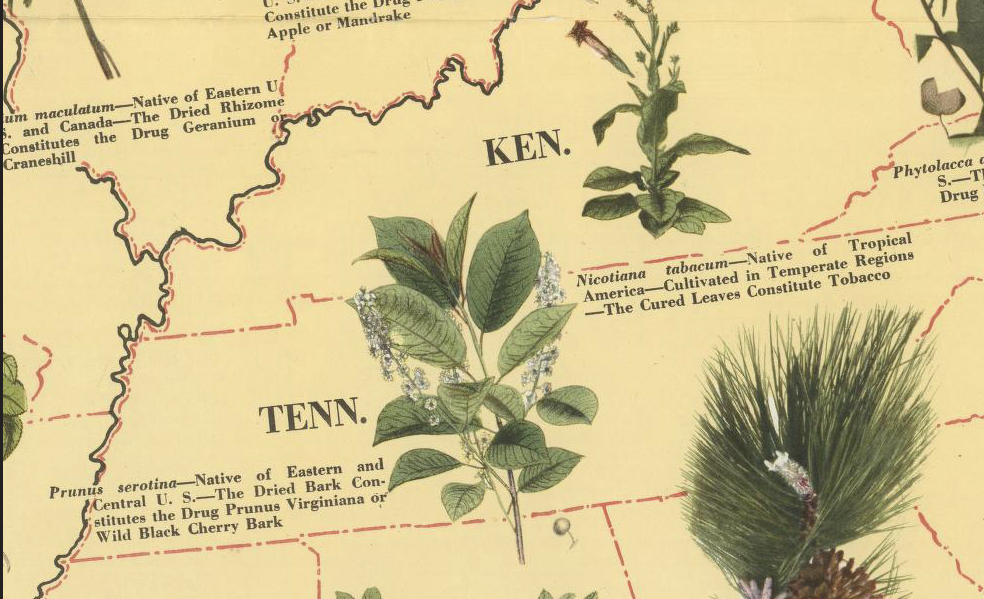

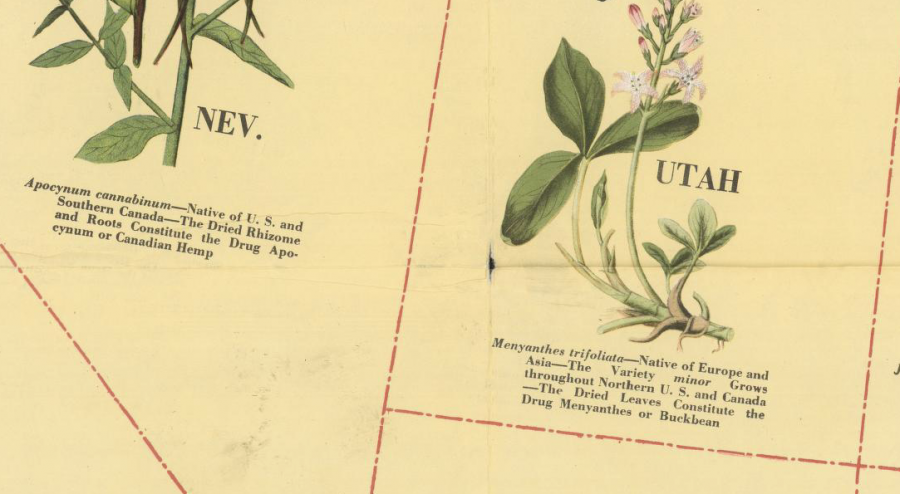

The map appeared during “Pharmacy Week” in October, when “pharmacists in Anglo-Saxon countries” promote their services. Losing sight of those important services, the Druggists’ Association writes, will lead to suffering, should the traditional pharmacist’s function “be impaired or destroyed by commercial trends.” Thus we have this visual demonstration of competence. The map identifies important species—native or cultivated—in each region of the country. In Kentucky, we see Nicotina tabacum, whose cured leaves, you guessed it, “constitute tobacco.” Across the country in Nevada, we are introduced to Apocynum cannabinum, “native of U.S. and Southern Canada—the dried rhizome and roots constitute the drug apocynum or Canadian hemp.”

The better-known Cannibus sativa also appears, in one of the boxes around the map’s border that introduce plants from outside North America, including Erythroxylon coca, from Bolivia and Peru, and Papaver somniferum, from which opium derives. Many of the other medications will be less familiar to us—and belong to what we now call naturopathy, herbalism, or, more generally, “traditional medicine.” Though these medicinal practices are many thousands of years old, the druggists try to project a cutting-edge image, assuring the map’s readers that “intense scientific study, expert knowledge, extreme care and accuracy are applied by the pharmacist to medicinal plants.”

While pharmacists today are highly-trained professionals, the part of their jobs that involved the making of drugs from scratch has been ceded to massive corporations and their research laboratories. The druggists of 1932 saw this coming, and no amount of colorful public relations could stem the tide. But it may be the case, given changing laws, changing attitudes, the backlash against overmedication, and the devastating opioid epidemic, that their craft is more relevant than it has been in decades, though today’s “druggists” work in marijuana dispensaries and health food stores instead of national pharmacy chains.

View and download the map in a high resolution scan at the David Rumsey Map Collection, where you can zoom in to every plant on the map and read its description.

via Slate

Related Content:

1,000-Year-Old Illustrated Guide to the Medicinal Use of Plants Now Digitized & Put Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

can find no way to download from

View and download the map in a high resolution scan

thanx

Click this link: https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~260602~5522896:Medicinal-plant-map-of-the-United‑S?sort=pub_date,pub_list_no,series_no#

Then click the “Export” button

Thanx, Josh — clearing out my Inbox and remembered my question — came back and saw your answer (never thought to hit that button) — doesn’t OC have a way to email alert for this sort of thing?

Having trouble downloading the map to my iphone. I do not see an export button, just a sharing icon. Thanks.