Magic is real—hear me out. No, you can’t solve life’s problems with a wand and made-up Latin. But there are academic departments of magic, only they go by different names now. A few hundred years ago the difference between chemistry and alchemy was nil. Witchcraft involved as much botany as spellwork. A lot of fun bits of magic got weeded out when gentlemen in powdered wigs purged weird sisters and gnostic heretics from the field. Did the old spells work? Maybe, maybe not. Science has become pretty reliable, I guess. Standardized classification systems and measurements are okay, but yawn… don’t we long for some witching and wizarding? A well-placed hex might work wonders.

Say no more, we’ve got you covered: you, yes you, can learn charms and potions, demonology and other assorted dark arts. How? For a onetime fee of absolutely nothing, you can enter magical books from the Early Modern Period.

T’was a veritable golden age of magic, when wizarding scientists like John Dee—Queen Elizabeth’s soothsaying astrologer and revealer of the language of the angels—burned brightly just before they were extinguished, or run underground, by orthodoxies of all sorts. The Newberry, “Chicago’s Independent Research Library Since 1887,” has reached out to the crowds to help “unlock the mysteries” of rare manuscripts and bring the diversity of the time alive.

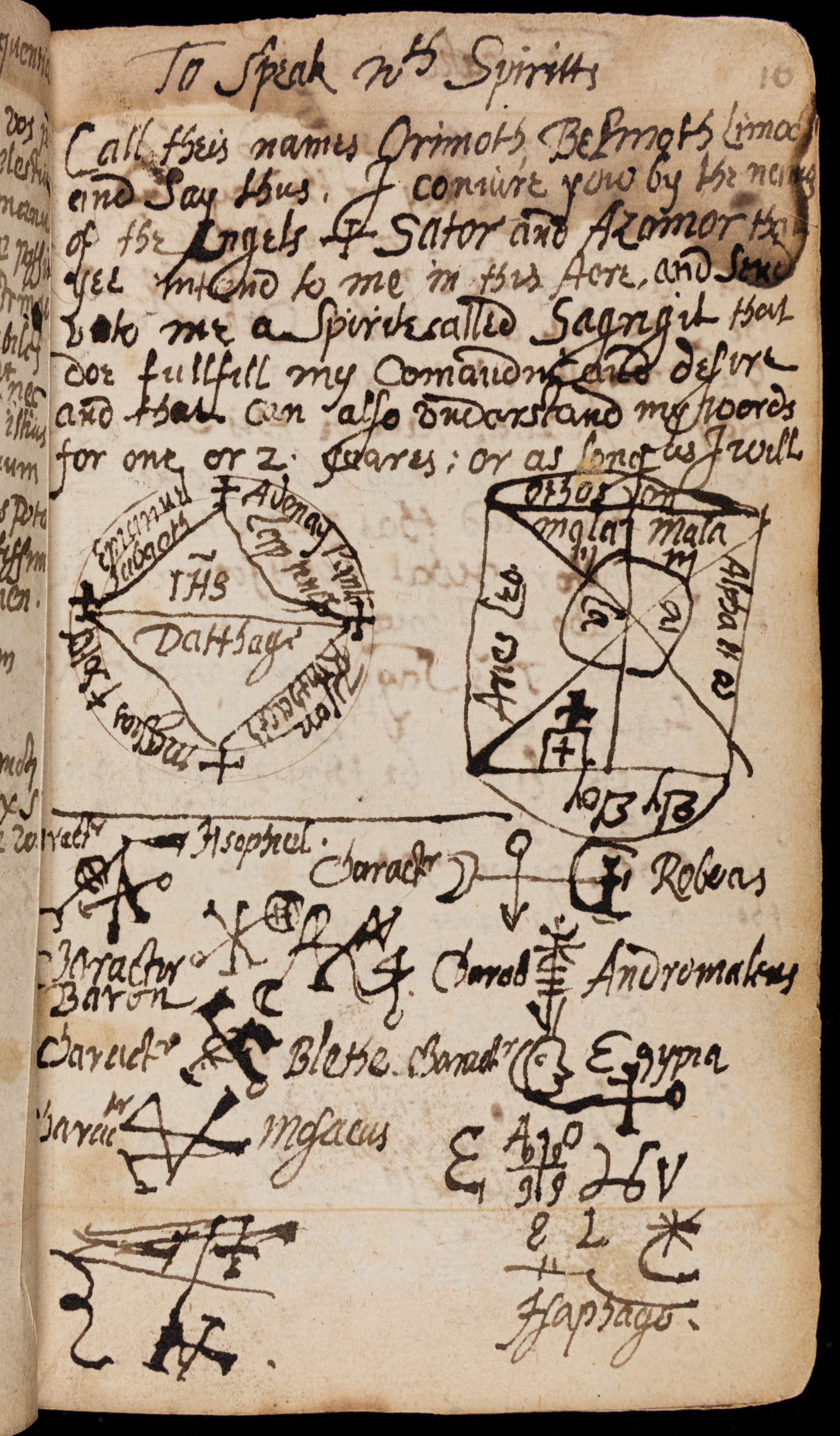

The library’s Transcribing Faith initiative gives users a chance to connect with texts like The Book of Magical Charms (above), by transcribing and/or translating the contents therein. Like software engineer Joseph Peterson—founder of the Esoteric Archives, which contains a large collection of John Dee’s work—you can volunteer to help the Newberry’s project “Religious Change, 1450–1700.” The Newberry aims to educate the general public on a period of immense upheaval. “The Reformation and the Scientific Revolution are very big, capital letter concepts,” project coordinator Christopher Fletcher tells Smithsonian.com, “we lose sight of the fact that these were real events that happened to real people.”

By aiming to return these texts to “real people” on the internet, the Newberry hopes to demystify, so to speak, key moments in European history. “You don’t need a Ph.D. to transcribe,” Fletcher points out. Atlas Obscura describes the process as “much like updating a Wikipedia page,” only “anyone can start transcribing and translating and they don’t need to sign up to do so.” Check out some transcriptions of The Book of Magical Charms—written by various anonymous authors in the seventeenth century—here. The book, writes the Newberry, describes “everything from speaking with spirits to cheating at dice to curing a toothache.”

Need to call up a spirit for some dirty work? Just follow the instructions below:

Call their names Orimoth, Belmoth Limoc and Say thus. I conjure you by the neims of the Angels + Sator and Azamor that yee intend to me in this Aore, and Send unto me a Spirite called Sagrigid that doe fullfill my comandng and desire and that can also undarstand my words for one or 2 yuares; or as long as I will.

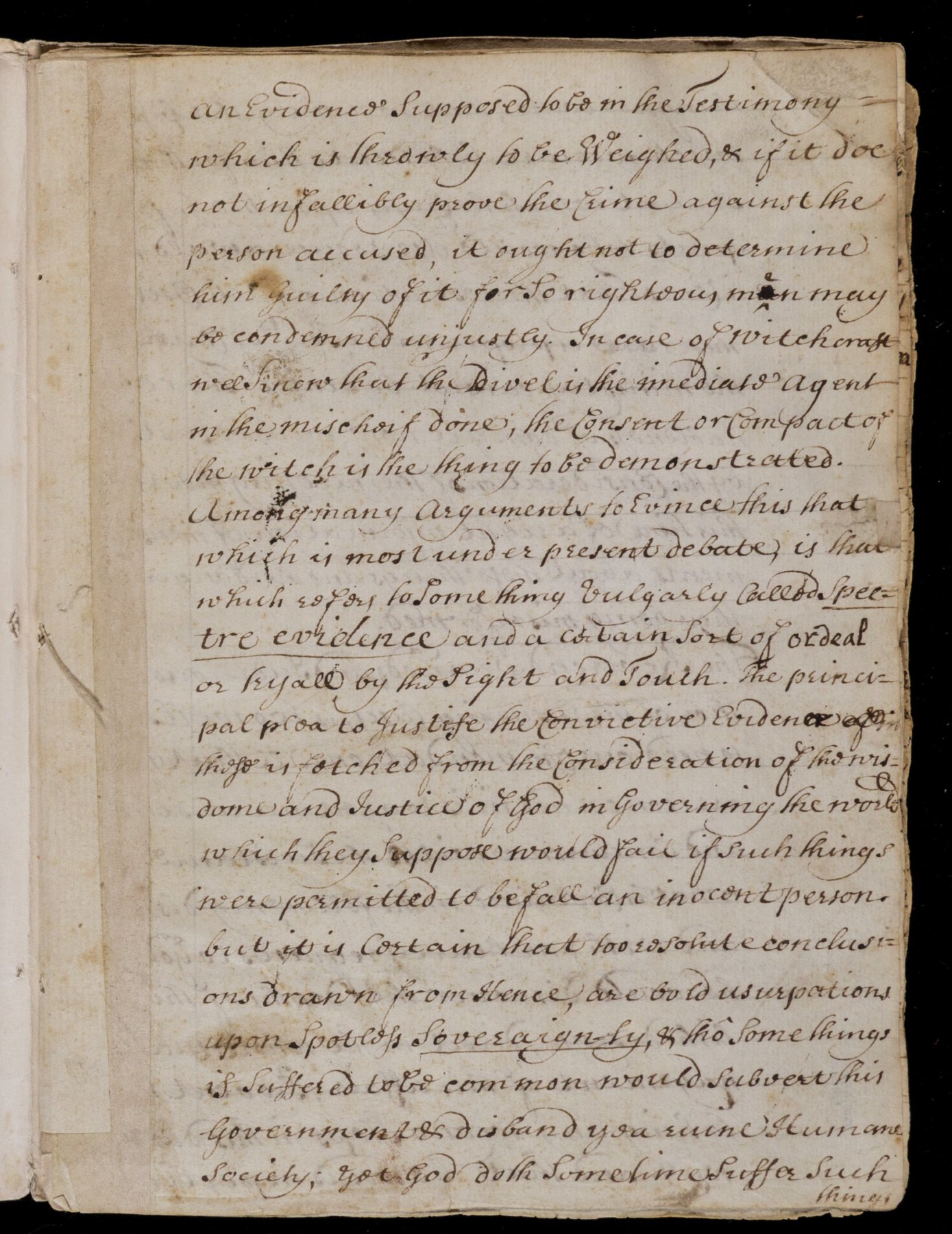

Seems simple enough, but of course this business did not sit well with some powerful people, including one Increase Mather, father of Cotton, president of Harvard, best known from his work on the Salem Witch Trials. Increase defended the prosecutions in a manuscript titled Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits, a page from which you can see further up. The text reads, in part:

an Evidence Supposed to be in the Testimony

which is throwly to be Weighed, & if it doe

not infallibly prove the Crime against the

person accused, it ought not to determine

him Guilty of it for So righteous may

be condemned unjustly.

Mather did not consider these to be show trials or “witchhunts” but rather the fair and judicious application of due process, for whatever that’s worth. Elsewhere in the text he famously wrote, “It were better that Ten Suspected Witches should escape, than that one Innocent Person should be Condemned.” Cold comfort to those condemned as guilty for likely practicing some mix of religion and early science.

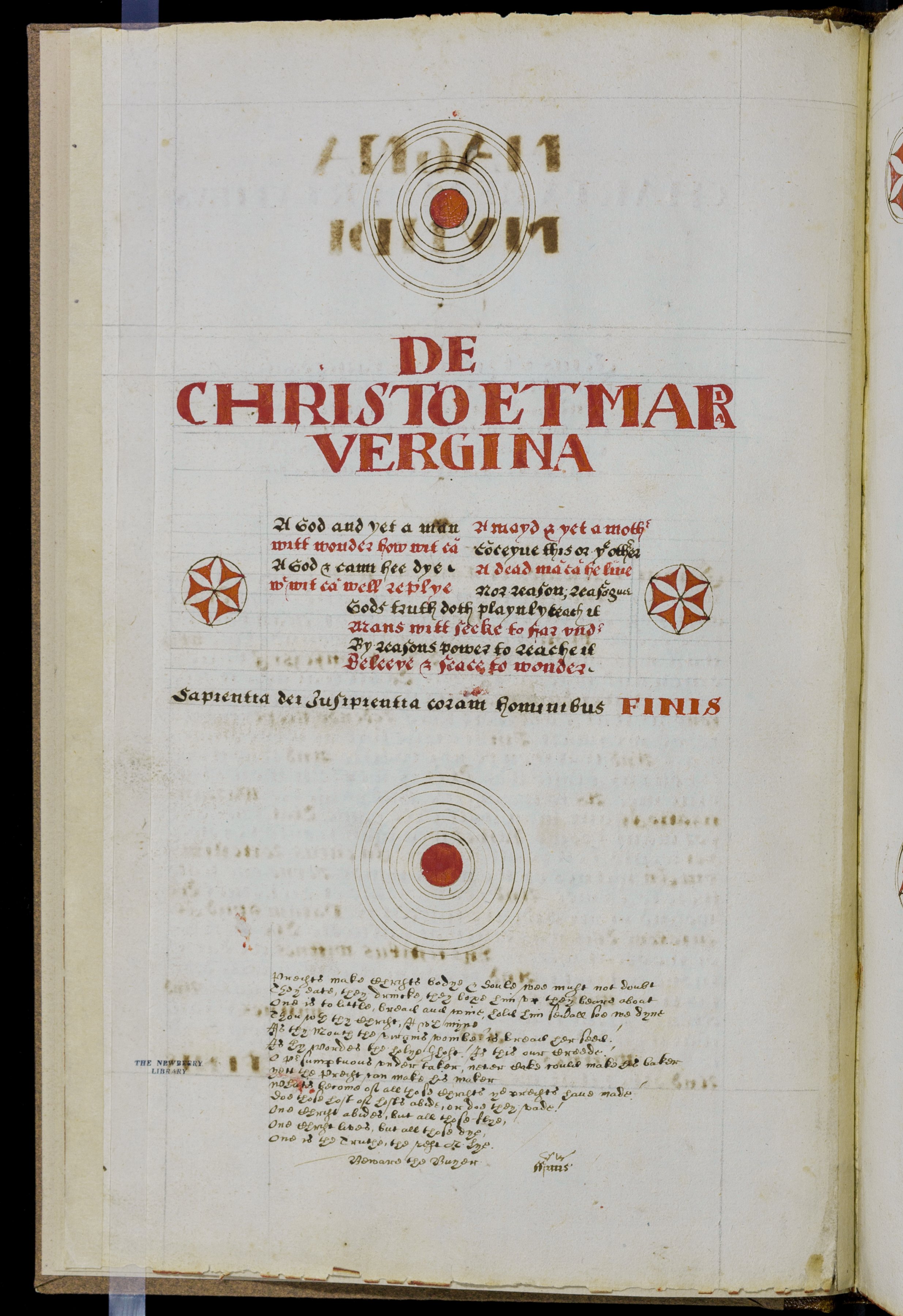

These texts are written in English and concern themselves with magical and spiritual matters expressly. Other manuscripts in the project’s archive roam more broadly across topics and languages, and “shed light on the entwined practices of religion and reading.” One “commonplace book,” for example (above), from sometime between 1590 and 1620, contains sermons by John Donne as well as “religious, political, and practical texts, including a Middle English lyric,” all carefully written out by an English scribe named Henry Feilde in order to practice his calligraphy.

Another such text, largely in Latin, “may have been started as early as the 16th century, but continued to be used and added to well into the 19th century. Its compilers expressed interest in a wide range of topics, from religious and moral questions to the liberal arts to strange events.” Books like these “reflected the reading habits of early modern people, who tended not to read books from beginning to end, but instead to dip in and out of them,” extracting bits and bobs of wisdom, quotations, recipes, prayers, and even the odd spell or two.

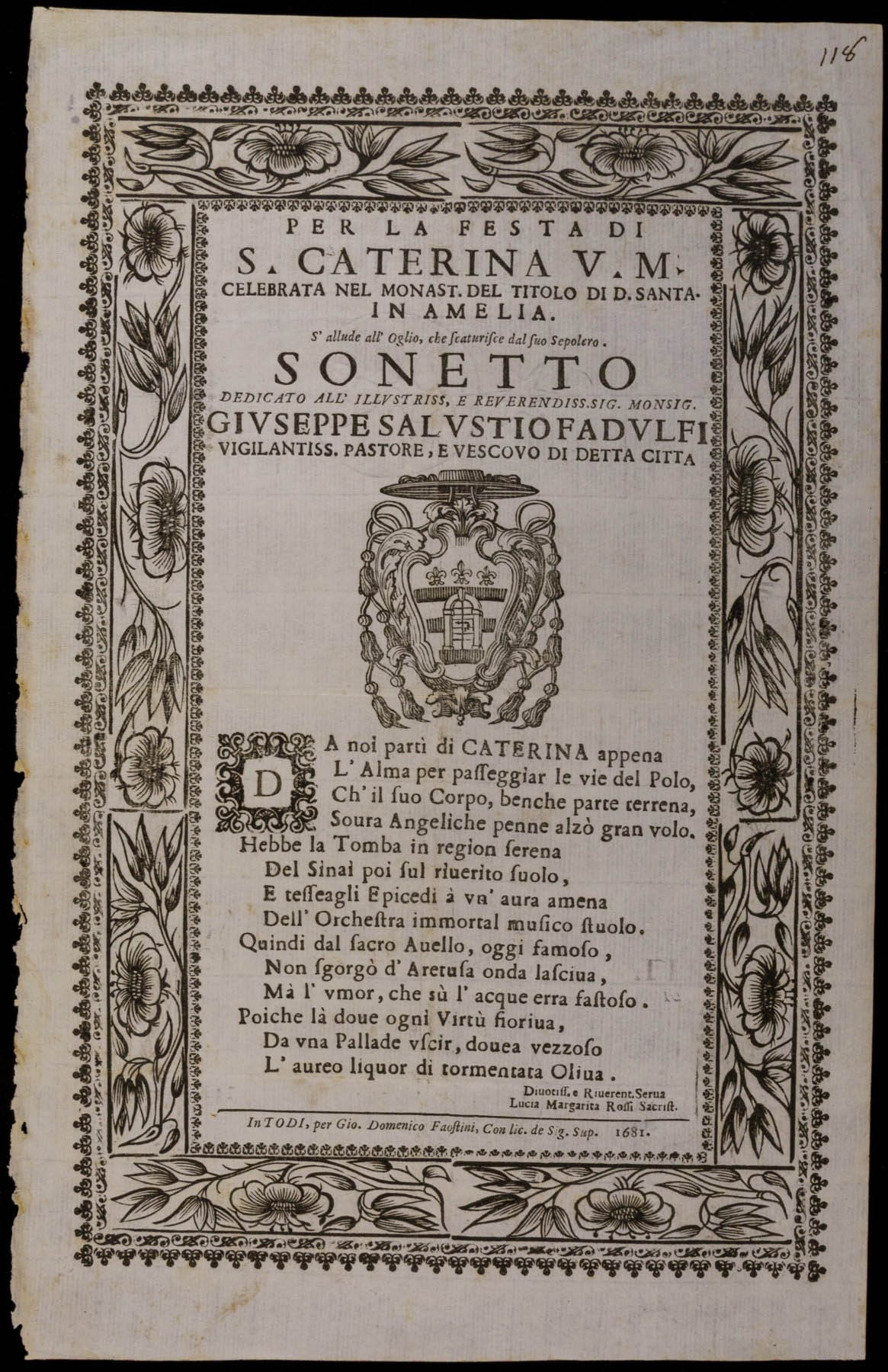

The final work in need of transcription/translation is also the only printed text, or texts, rather, a collection of Italian religious broadsides, advertising “public celebrations and commemorations of Catholic feast days and other religious occasions.” Hardly summoning spirits, though some may beg to differ. If you’re so inclined to take part in opening the secrets of these rare books for lay readers everywhere, visit Transcribing Faith here and get to work.

via Smithsonian/ Atlas Obscura

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply