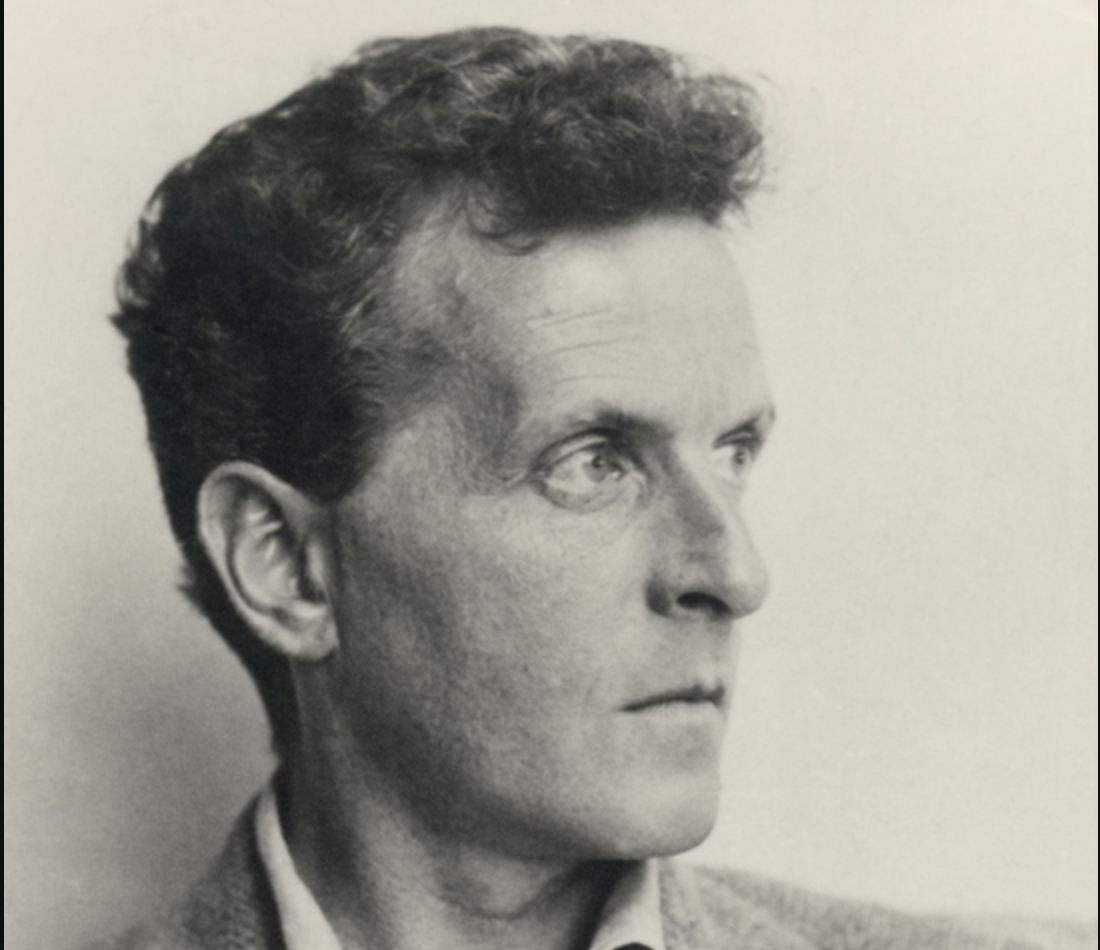

Image by Austrian National Library, via Wikimedia Commons

Faced with the question, “who are the most important philosophers of the 20th century?,” I might find myself compelled to ask in turn, “in respect to what?” Ethics? Political philosophy? Philosophy of language, mind, science, religion, race, gender, sexuality? Phenomenology, Feminism, Critical theory? The domains of philosophy have so multiplied (and some might say siloed), that a number of prominent authors, including eminent philosophy professor Robert Solomon, have written vehement critiques against its entrenchment in academia, with all of the attendant pressures and rewards. Should every philosopher of the past have had to run the gauntlet of doctoral study, teaching, tenure, academic politics and continuous publication, we might never have heard from some of history’s most luminous and original thinkers.

Solomon maintains that “nothing has been more harmful to philosophy than its ‘professionalization,’ which on the one hand has increased the abilities and techniques of its practitioners immensely, but on the other has rendered it an increasingly impersonal and technical discipline, cut off from and forbidding to everyone else.” He championed “the passionate life” (say, of Nietzsche or Camus), over “the dispassionate life of pure reason…. Let me be outrageous and insist that philosophy matters. It is not a self-contained system of problems and puzzles, a self-generating profession of conjectures and refutations.” I am sympathetic to his arguments even as I might object to his wholesale rejection of all academic thought as “sophisticated irrelevancy.” (Solomon himself enjoyed a long career at UCLA and the University of Texas, Austin.)

But if forced to choose the most important philosophers of the late 20th century, I might gravitate toward some of the most passionate thinkers, both inside and outside academia, who grappled with problems of everyday personal, social, and political life and did not shy away from involving themselves in the struggles of ordinary people. This need not entail a lack of rigor. One of the most passionate of 20th century thinkers, Ludwig Wittgenstein, who worked well outside the university system, also happens to be one of the most difficult and seemingly abstruse. Nonetheless, his thought has radical implications for ordinary life and practice. Perhaps non-specialists will tend, in general, to accept arguments for philosophy’s everyday relevance, accessibility, and “passion.” But what say the specialists?

One philosophy professor, Chen Bo of Peking University, conducted a survey along with Susan Haack of the University of Miami, at the behest of a Chinese publisher seeking important philosophical works for translation. As Leiter Reports reader Tracy Ho notes, the two professors emailed sixteen philosophers in the U.S., England, Australia, Germany, Finland, and Brazil, asking specifically for “ten of the most important and influential philosophical books after 1950.” “They received recommendations,” writes Ho, “from twelve philosophers, including: Susan Haack, Donald M. Borchert (Ohio U.), Donald Davidson, Jurgen Habermas, Ruth Barcan Marcus, Thomas Nagel, John Searle, Peter F. Strawson, Hilary Putnam, and G.H. von Wright.” (Ho was unable to identify two other names, typed in Chinese.)

The results, ranked in order of votes, are as follows:

1. Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations

2. W. V. Quine, Word and Object

3. Peter F. Strawson, Individuals: An Essay in Descriptive Metaphysics

4. John Rawls, A Theory of Justice

5. Nelson Goodman, Fact, Fiction and Forecast

6. Saul Kripke, Naming and Necessity

7. G.E.M. Anscombe, Intention

8. J. L. Austin, How to do Things with Words

9. Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

10. M. Dummett, The Logical Basis of Metaphysics

11. Hilary Putnam, The Many Faces of Realism

12. Michel Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences

13. Thomas Nagel, The View From Nowhere

14. Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State and Utopia

15. R. M. Hare, The Language of Morals and Freedom and Reason

16. John R. Searle, Intentionality and The Rediscovery of the Mind

17. Bernard Williams, Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy, Descartes: The Project of Pure Enquiry and Moral Luck: Philosophical Papers 1973–1980

18. Karl Popper, Conjecture and Refutations

19. Gilbert Ryle, The Concept of Mind

20. Donald Davidson, Essays on Action and Event and Inquiries into Truth and Interpretation

21. John McDowell, Mind and World

22. Daniel C. Dennett, Consciousness Explained and The Intentional Stance

23. Jurgen Habermas, Theory of Communicative Action and Between Facts and Norm

24. Jacques Derrida, Voice and Phenomenon and Of Grammatology

25. Paul Ricoeur, Le Metaphore Vive and Freedom and Nature

26. Noam Chomsky, Syntactic Structures and Cartesian Linguistics

27. Derek Parfitt, Reasons and Persons

28. Susan Haack, Evidence and Inquiry

29. D. M. Armstrong, Materialist Theory of the Mind and A Combinatorial Theory of Possibility

30. Herbert Hart, The Concept of Law and Punishment and Responsibility

31. Ronald Dworkin, Taking Rights Seriously and Law’s Empire

As an addendum, Ho adds that “most of the works on the list are analytic philosophy,” therefore Prof. Chen asked Habermas to recommend some additional European thinkers, and received the following: “Axel Honneth, Kampf um Anerkennung (1992), Rainer Forst, Kontexte der Cerechtigkeit (1994) and Herbert Schnadelbach, Kommentor zu Hegels Rechtephilosophie (2001).”

The list is also overwhelmingly male and pretty exclusively white, pointing to another problem with institutionalization that Solomon does not acknowledge: it not only excludes non-specialists but can also exclude those who don’t belong to the dominant group (and so, perhaps, excludes the everyday concerns of most of the world’s population). But there you have it, a list of the most important, post-1950 works in philosophy according to some of the most eminent living philosophers. What titles, readers, might get your vote, or what might you add to such a list, whether you are a specialist or an ordinary, “passionate” lover of philosophical thought?

via Leiter Reports

Related Content:

A History of Philosophy in 81 Video Lectures: From Ancient Greece to Modern Times

Oxford’s Free Introduction to Philosophy: Stream 41 Lectures

Introduction to Political Philosophy: A Free Yale Course

Free Online Philosophy Courses

44 Essential Movies for the Student of Philosophy

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leo Strauss: “Natural Right and History” and “Persecution and the Art of Writing”

Ryle’s great work actually came out in 1949. I suggest that the following deserve strong consideration: Feyerabend’s Against Method, Gadamer’s Truth and Method, and Dray’s Laws and Explanation in History.

I’m at a loss to understand how the most comprehensive, consistent, and fundamentally based philosopher of all time, covering metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, politics, and aesthetics, could be left off the list of most important philosophers and philosophies since 1950. I am referring to Ayn Rand and Objectivism.

For better or worse, Ms. Rand’s work has not been influential within academic philosophy. Most philosophers would probably regard her as just a popular author. They would not regard her as having written anything scholarly on, say, ethics–her Objectivism, as I recall, is just garden variety ethical egoism. And they would probably not think of her as having written anything *at all* on, say, metaphysics or epistemology. Did she write on these? On subjects like the nature of properties and relations? Or on modal metaphysics, consciousness, intension and extension, the analytic/synthetic distinction, apriority & aposteriority, theories of epistemic justification, confirmational holism, Molinist refutations of the problem of evil, natural theological arguments, the nature of explanation, or any other highly technical such topics that have been at the fore of philosophical discussion for the past half-century? I am not aware of her having written anything on any of those.

Surely Ayer’s Language, Truth and Logic should feature on the list — hugely influential.

Keiji Nishitani, “Religion and Nothingness” and “The Self-Overcoming of Nihilism”

The number of academic philosophy departments multiplied, not the domains of philosophy, when special interests or activists began to use “theory” as a means in their fight for power.

That’s because she’s shallow.

Exactly.

Jean Piaget and Barbel Inhelder, The Psychology of the Child, 1950

Alan Turing, Computing machinery and intelligence, 1950

Isaiah Berlin, The Age of Enlightenment, 1956

Ayn Rand, Atlas Shrugged, 1957

Claude Levi-Strauss, Structural Anthropology, 1959

Carl Rogers, On Becoming a Person: A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy, 1961

Murray Rothbard, Man, Economy, and State, 1962

Fernand Braudel, Civilisation matérielle, 1967

Brent Berlin and Paul Kay, Basic Color Terms: Their Universality and Evolution, 1969

Paul Karl Feyerabend, Against Method: Outline of an Anarchistic Theory of Knowledge, 1970

Nicolas Bourbaki, Éléments de mathématique, 1970

B. F. Skinner, Beyond Freedom and Dignity, 1971

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, 1972

A. J. Ayer, The Central Questions Of Philosophy, 1973

Imre Lakatos, Proofs and Refutations, 1976

Larry Laudan, Progress and Its Problems: Towards a Theory of Scientific Growth, 1977

Stanley Cavell, The Claim of Reason: Wittgenstein, Skepticism, Morality, and Tragedy, 1979

Ray Kurzweil, The Age of Intelligent Machines, 1990

J.L. Schellenberg, Divine Hiddenness and Human Reason

Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man, 1992

User’s book came out in 1936; this list is 1950–2000.

quentin meillassoux after finitude !

That’s Ayer’s.

Meillassoux’s book came out in 2008. C’mon, people, read the headline!

Ayer’s Language, Truth, and Logic came out in 1936. The Central Questions of Philosophy was a later, and much more wide-ranging book, in which he actually rejects many of his old ideas expressed in Language, Truth, and Logic.

Quentin Meillassoux, After Finitude was published after 2000.

Rand. Ha ha ha.

[The list is also overwhelmingly male and pretty exclusively white, pointing to another problem with institutionalization that Solomon does not acknowledge: …]

Any non-white / non male author who should be included ?

The headline is “The 43 Most Important Philosophy Books Written Between 1950–2000”. The list is overwhelmingly male and white because the 43 Most Important Philosophy Books Written Between 1950–2000 were written by overwhelmingly male and pretty exclusively white people. Non-White non-males are free to write important philosophy books if they want. There’s as muc stopping them as there is any average person, who will most likely not write one of the 43 most important philosophy books of the last half-century.

For those who would Know.

Ayn Rand died in 1983 with her philosophy completed but not well organized in a single book. Leonard Peikoff, a student of hers, codified her philosophy in his book “OBJECTIVISM: the philosophy of AYN RAND”, published in 1991. For those who would like to make their own decisions I recommend studying this book. Currently, Objectivism is being promoted by The Ayn Rand Institute in Irvine, California.

Jin Wright

Hi, there are two typos in the name of Ricoeur’s book (#25). It should be “La Métaphore Vive”, not “Le Metaphore Vive”.

For those who would know, addendum.

It occured to me that certain of Ayn Rand’s talks and writings before her death would certainly be of interest to you. Of these “Philosophy: Who Needs It?”, tops the list. This book begins with a talk Miss Rand gave to a graduating class at West Point Military Academy in 1974, and contains some 18 short articles on various aspects of Objectivism.

Jim Wright

Somewhat surprised Rorty’s Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature didn’t make it, but I guess a lot of professional philosophers still have some kind of grudge against RR.

Ayn Rand isn’t on the list because no professional philosophers take her seriously. They don’t take her seriously because her work is, philosophically speaking, worthless. (Her literary attempts are also worthless, but I guess that’s a different conversation.)

The problem with Rand’s work is not that it’s worthless. Unoriginal, maybe. Unpopular, certainly. But what philosophers mean when they say her work is worthless is that they don’t agree with it. It’s been like that throughout the history of philosophy.

I am one of the ordinary type of philosophy lovers. I think Joel has a point about the Rand critics. Their rather rude dismissal here smacks of piling on. In terms of strategy it reminds me of Hobbes decision to label anything that contradicted his materialistic premises as “meaningless”. Problem solved, I suppose, but perhaps Hobbes’s move, in retrospect, was reductive thinking which restricted the field unnecessarily. Mind you, I’m not saying Rand is a great philosopher, or even a coherent one. But, she does have her admirers some of whom we’ve heard from. I would think that her exclusion from this list of the “greats” of this 50-year span should have satisfied her critics.

“But what philosophers mean when they say her work is worthless is that they don’t agree with it. It’s been like that throughout the history of philosophy.” — This is wholly incorrect. An enormous part of the activity of philosophers consists in identifying points of disagreement with other philosophers, explaining why they’re wrong, and proposing alternatives. This has nothing to do with declaring the criticized philosophy worthless; on the contrary, the engagement with it shows that it is considered to have value as philosophy; that activity of disagreement and argument is itself a huge part of what philosophy is. Aristotle didn’t agree with Plato on many questions; Aristotle did not thereby regard Plato’s work as worthless. This is how it’s been throughout the history of philosophy.

With regard to Rand, the disregard for her work is shown precisely by the lack (for the most part) of this kind of engagement with it. From the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: “Whereas Rand’s ideas and mode of presentation make Rand popular with many non-academics, they lead to the opposite outcome with academics. She developed some of her views in response to questions from her readers, but never took the time to defend them against possible objections or to reconcile them with the views expressed in her novels. Her philosophical essays lack the self-critical, detailed style of analytic philosophy, or any serious attempt to consider possible objections to her views. Her polemical style, often contemptuous tone, and the dogmatism and cult-like behavior of many of her fans also suggest that her work is not worth taking seriously.”

For Those who would Know III.

Those who reject Ayn Rand’s philosophy are the Intellectuals, who presumably have read it, who have their personal reasons, and the Laymen, many of whom have not read her philosophy, and are reciting what they’ve been told.

How much better to have read it and to make your own judgement? Perhaps to start by reading her “Philosophy: Who Needs It”.

Jim Wright

Considering life is already far too short to read everything that’s actually worth reading, I’d say it’s better not to waste your time reading someone whose work has been essentially unanimously rejected by those trained in the field.

Rand was intelligent and talented, but she was a crank, and her work attracts cranks. Or intelligent, disaffected teenagers, who in most cases go through a Rand phase before outgrowing her immature vision of the solitary, misunderstood genius/hero who has to make his (and it usually is his) lonely, unassisted way through a world designed by and for the mediocre.

It wouldn’t matter, except that some of the people who never outgrew this have ascended to positions of political power in the US, where they are able put this ideology in practice in the service of the peculiarly American notion that unfettered, deregulated capitalism, universal privatization, and the further enrichment of the already rich are somehow identical to human freedom as such. Rand is consonant with that, especially for people who don’t have any real philosophical acumen.

Of course, there are intellectually responsible versions of the ideas Rand was getting at. Nozick’s Anarchy, State, and Utopia (#14 in the list); Milton Friedman; some of Nietzsche. Oddly enough, you don’t have to go to a Nozick Institute or Friedman Institute or Nietzsche Institute to find people who take them seriously.

I only see 31, not 43. The list stops at “31. Ronald Dworkin, Taking Rights Seriously and Law’s Empire

As an addendum, Ho adds that “most of the works on the list are analytic philosophy,” therefore Prof. Chen asked .….” No more numbered items.

Apparently something should be between “.… Law’s Empire” and “As an addendum.….”

Thanks a lot for the list!

Nieznany:

I’ll respond to one paragraph at a time:

“…better not to waste your time reading someone whose work has been essentially unanimously rejected by those trained in the field.”

You’ve heard of ad verecundiam and ad populum, haven’t you?

“…but she was a crank, and her work attracts cranks. Or intelligent, disaffected teenagers, who in most cases go through a Rand phase before outgrowing her immature vision…”

If we’re going to disqualify philosophers who were cranks, I’m afraid we wouldn’t be left with many (also, google ‘ad hominem’ please). And about growing out of a ‘Rand Phase…”, you’ve heard of Nietzsche, right?

“…peculiarly American notion that unfettered, deregulated capitalism, universal privatization, and the further enrichment of the already rich…”

Ah! Now we’ve gotten to the meat of the matter. Anti-Rand sentiment really stems from opposition to America and capitalism. That’s what it’s really about, most of the time. Ask those Marxist professors how their political philosophy worked out in the Soviet Union and elsewhere.

re Joel Dick:

Ad populum doesn’t fit here as I am appealing specifically to the opinions of experts, not “a lot of people.”

And that appeal on my part is of course not intended to have logically conclusive force, but to serve as a useful heuristic, given that we all have to make decisions as to how to allocate the very limited resource of our time available for reading. Taking into account an overwhelming consensus of expert opinion is an appropriate tactic for that.

However, I am happy to cop to engaging in ad hominem discourse against Ms. Rand, because that is the only level of engagement her work deserves, particularly considering her own ad hominem dismissal of the most important figures in Western philosophy as “witch doctors.”

As for anti-capitalism, I went out of my way to contrast Rand with two influential theorists of capitalism in its most market-friendly, libertarian form — Nozick and Friedman. I don’t agree with them either, but at least their work deserves serious intellectual engagement and response.

Nietzsche is a somewhat different case as his work doesn’t really address capitalism or “political philosophy” in the usual academic sense, but he can be read in places as advocating a kind of ethical egoism that you could also associate with Rand.

Nietzsche was a much better writer, and broader and deeper thinker, than Rand, of course. Relegating him to an immature phase that teenagers go through is ignorant and/or dishonest.

Herbert Marcuse, One Dimensional Man; Martin Heidegger, Die Technik und die Kehre; Albert Borgmann, Technology and the Character of Contemporary Life; Moishe Postone, Time, Labor, and Social Domination

Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (1958); Raya Dunayevskaya, Philosophy and Revolution (1973); Gillian Rose, Hegel contra Sociology (1981). I was going to add de Beauvoir but her most significant philosophical writing was pre-1950.

I just wanted to say thanks to Nieznany for setting Joel straight. Rand fanatics always act like she’s disliked because of her political views, yet refuse to acknowledge the widespread respect and admiration among academic philosophers for Nozick, who espoused quite libertarian views but did it in a rigorous, thoughtful, and philosophically substantive way. Rand was a dogmatist who couldn’t write a half-decent argument and who couldn’t engage with any sort of disagreement, which helps to explain why essentially all of her diehard fans are people who haven’t read much other philosophy.

Typos / errata in penultimate paragraph:

‘As an addendum, Ho adds that “most of the works on the list are analytic philosophy,” therefore Prof. Chen asked Habermas to recommend some additional European thinkers, and received the following: “Axel Honneth, Kampf um Anerkennung (1992), Rainer Forst, Kontexte der Gerechtigkeit [not “Cerechtigkeit”] (1994) and Herbert Schnädelbach [not “Schnadelbach”], Kommentor zu Hegels Rechtsphilosophie [not “Rechtephilosophie”](2001).”’

PS: At least two of these has been translated into English.

Axel Honneth, Kampf um Anerkennung

> The Struggle for Recognition: The Moral Grammar of Social Conflicts. Polity Press, 1995

Rainer Forst, Kontexte der Gerechtigkeit

> Contexts of Justice. Political Philosophy beyond Liberalism and Communitarianism. University of California Press, 2002

One of the books mentioned I do not see with simple web searches; perhaps Habermas had in mind

Herbert Schnädelbach, Hegels Philosophie – Kommentare zu den Hauptwerken. 3 Bände: Band 2: Hegels praktische Philosophie.

No a for no kant hegel Marx Spinoza… I codgo on.

No Buddhism or Vedic thought. This us an absurd list

Mario Bunge is one of the greatest SCIENTIFIC PHILOSOPHERS today. His most important wirk: “Teatrise on Basic Philosoohy”

Since Ortega y Gasset died in 1955, and some works were published

posthumously as well, I should have liked to seen his name on the list. Other names listed, I for my part, do not think all that

contributory of critical new thought, like Rawls for one. Ortega’s

Historical Reason was a new revelation overturning Cartesian

idealism and methodology; and his Philosophy paves the way for the

Carsonian epoch, with attention upon the circumstances of environment

and climate as co-existing with the vital radical reality that is the human individual living in happenstance. Or so I think. For me, Ortega

y Gasset’s works are foundational, no less than Parmenides, Aristotle,

and Descartes. Jacques Barzun, cultural historian and author of ‘From Dawn to Decadence,’ wrote that sooner or later, people would have to listen to Ortega y Gasset. I couldn’t agree more, Ortega is the Philosopher for the Carsonian revelation and epoch.

What is _The Concept of Mind_, published in 1949, doing in a list of books published between 1950 and 2000?

Also, what value — or at least representative value — in a survey that polled sixteen philosophers and got twelve responses!

All in all: this enterprise seems a mess.