While the value of slaves in the U.S. from the colonial period to the Civil War rose and fell like other market goods, for the most part, enslaved people constituted the most valuable kind of property, typically worth even more than land and other highly valued resources. In one study, three University of Kansas historians estimate that during most of the 18th century in South Carolina, slaves “made up close to half of the personal wealth recorded in probate inventory in most decades.” By the 19th century, slaveholders had begun taking out insurance policies on their slaves as Rachel L. Swarns documents at The New York Times.

“Alive,” Swarns writes, “slaves were among a white man’s most prized assets. Dead, they were considered virtually worthless…. By 1847, insurance policies on slaves accounted for a third of the policies in a firm”—New York Life—“that would become one of the nation’s Fortune 100 companies.” Given the huge economic incentives for perpetuating the system of chattel slavery, the fact that people did not want to be held in forced labor for life—and to condemn their children and grandchildren to the same—presented slaveholders with a serious problem.

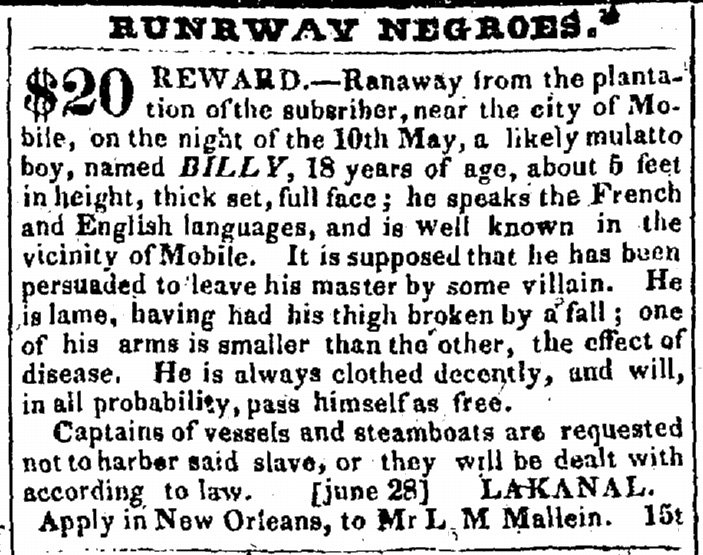

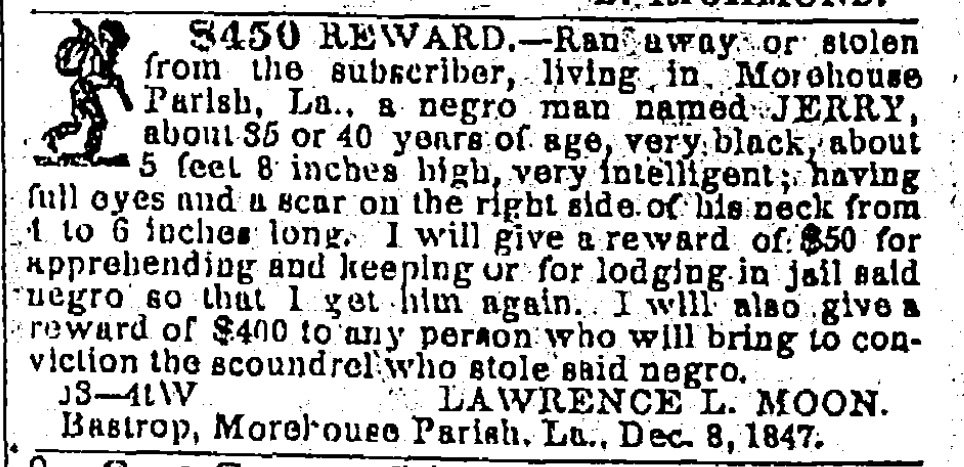

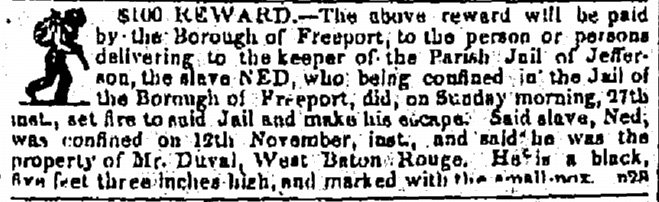

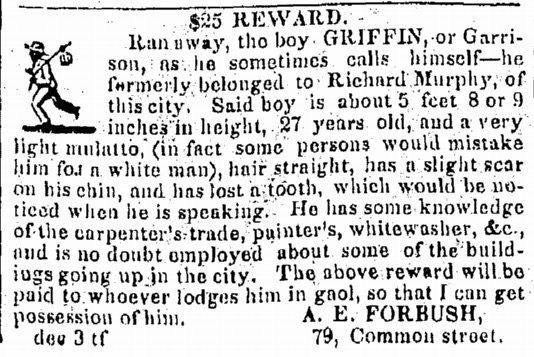

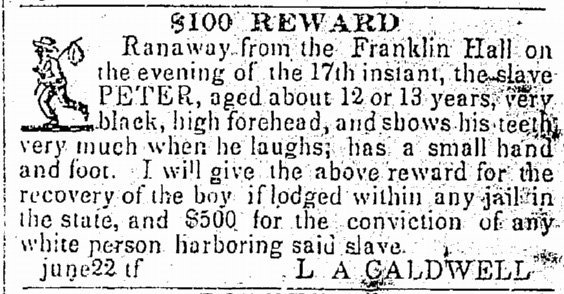

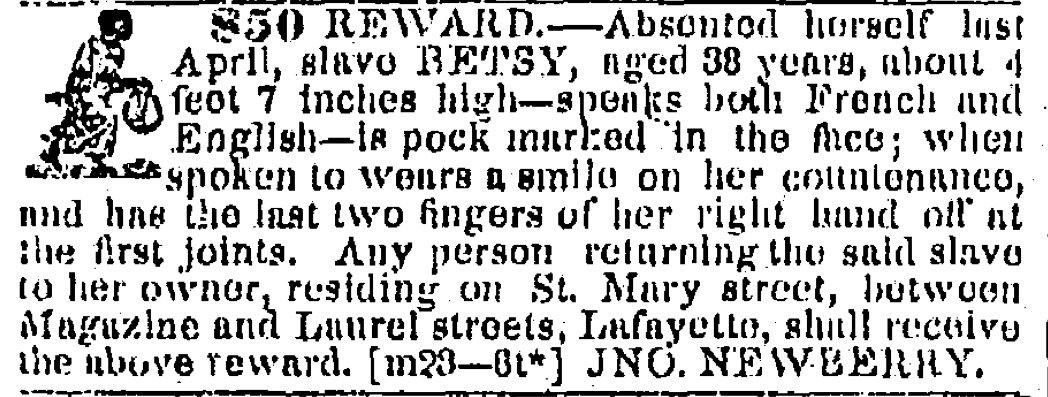

For over 250 years, countless numbers of enslaved people attempted to escape to freedom. And thousands of slaveowners ran newspaper ads to try and recover their investments. These ads are likely familiar from textbooks and historical articles on slavery; they have long been used singly to illustrate a point, “but they have never been systematically collected,” notes Cornell University’s Freedom on the Move project, which intends to “compile all North American slave runaway ads and make them available for statistical, geographical, textual, and other forms of analysis.” While the database is still in progress, examples of the ads are being shared on the @fotmproject Twitter account.

The ongoing project presents a tremendous opportunity for historical scholars of the period. “If we could collect and collate all of these ads,” the project’s researchers write, “we would create what might be the single richest source of data possible for understanding the lives of the approximately eight million people who were enslaved in the U.S.” It is estimated that 100,000 or more such ads survive “from the colonial and pre-Civil War U.S.,” though they might represent a fraction of those published, and of the number of attempted, and successful, escapes.

Many of the ads casually reveal evidence of brutal treatment, listing scars and brands, missing fingers, speech impediments, and halting walks. They show many of the escaped slaves to have been skilled in several trades and speak multiple languages. A large number of the escapees are children. As University of New Orleans historian Mary Niall Mitchell tells Hyperallergic, “ironically, in trying to retrieve their property—the people they claimed as things—enslavers left us mounds of evidence about the humanity of the people they bought and sold.” (Mitchell is one of the projects three lead researchers, along with University of Alabama’s Joshua Rothman and Cornell’s Edward Baptist, author of The Half Has Never Been Told.)

The slaveholders who ran ads also left evidence of what they made themselves believe in order to hold people as property. One ad describes a runaway slave named Billy as having been “persuaded to leave his master by some villain,” as though Billy must surely have been contented with his lot. In the overwhelming majority of cases, we will never know with certainty what most people thought about being enslaved. Yet the fact that hundreds of thousands attempted to escape at great personal risk, often without any help—to such a degree that extreme, inflammatory measures like the Fugitive Slave Act were eventually deemed necessary—should offer sufficient testament, if the relatively few written narratives aren’t enough. “For some” of the people in the ads, says Mitchell, “this may be the only place something about them survives, in any detail, in the written record,”

Freedom on the Move, writes Hyperallergic’s Allison Meier, “expands on the history of resistance against slavery in the 18th and 19th centuries.” It offers a compelling picture of two intolerably irresolvable views—those of slaveholders who viewed enslaved people as proprietary investments; and those of the enslaved who refused to be reduced to objects for others’ pleasure and profit.

Visit Freedom on the Move and find out more.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply