When you think Chinese Revolution, surely you think of Mao Zedong and the People’s Republic coming to power in 1949, a history that overshadows an earlier seismic event that overthrew the last imperial dynasty and brought the short-lived Republic of China into being. If your sense of this history is somewhat vague, you’re not alone—even those who know the events and the principle actors well are hesitant to ascribe any definitive interpretations to the 1911, or Xinhai, Revolution. “Significant thinkers and activists have… remained hesitant in their final judgment on it,” writes Oxford University’s Rana Mitter: “Its meaning continues to be highly contested… separated from any one path of historical interpretation.”

There is a general consensus, at least, among historians of the period and contemporary chroniclers alike that the Xinhai Revolution was foremost a struggle to modernize the country and get free of colonialist encroachments on Chinese self-determination. As in Russia around the same time, the concept of political modernization had many different meanings to the competing factions seeking to supplant the moribund imperial system.

“Some hoped for a constitutional framework, i.e., parliamentary monarchy,” notes University of Kansas professor Anna M. Cienciala, “while others worked for a democratic republic. Most wanted the abolition of the feudal-Confucian system; all wanted the abolition of foreign privilege and the unification of their vast country.”

This last hope would be dashed. The strongest faction succeeded in gaining support from wealthy Chinese living abroad, who funded the efforts of revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen, a medical doctor raised in Hawaii who began in the late 19th century “to devote himself to political work for the overthrow of the Qing Dynasty” in order to “create a strong, unified, modern, Chinese republic” with a socialist economy. Despite support from the military, the Republic established in 1912 “proved a miserable failure,” Cienciala argues, and the country fragmented under the rule of various warlords, then suffered through several more upheavals and an attempted Qing restoration in the ensuing decades while the Communists consolidated power.

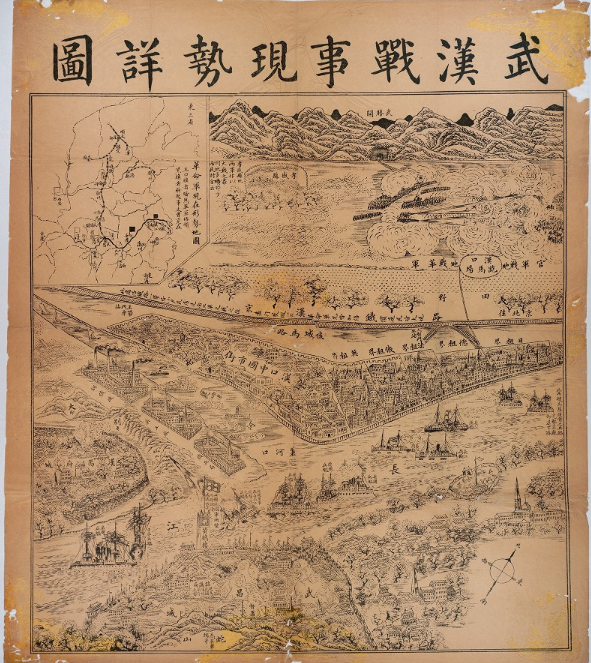

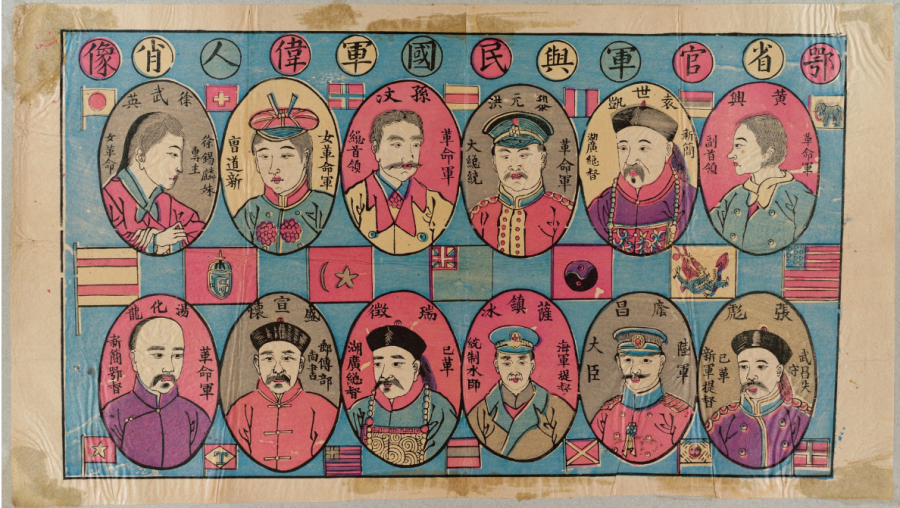

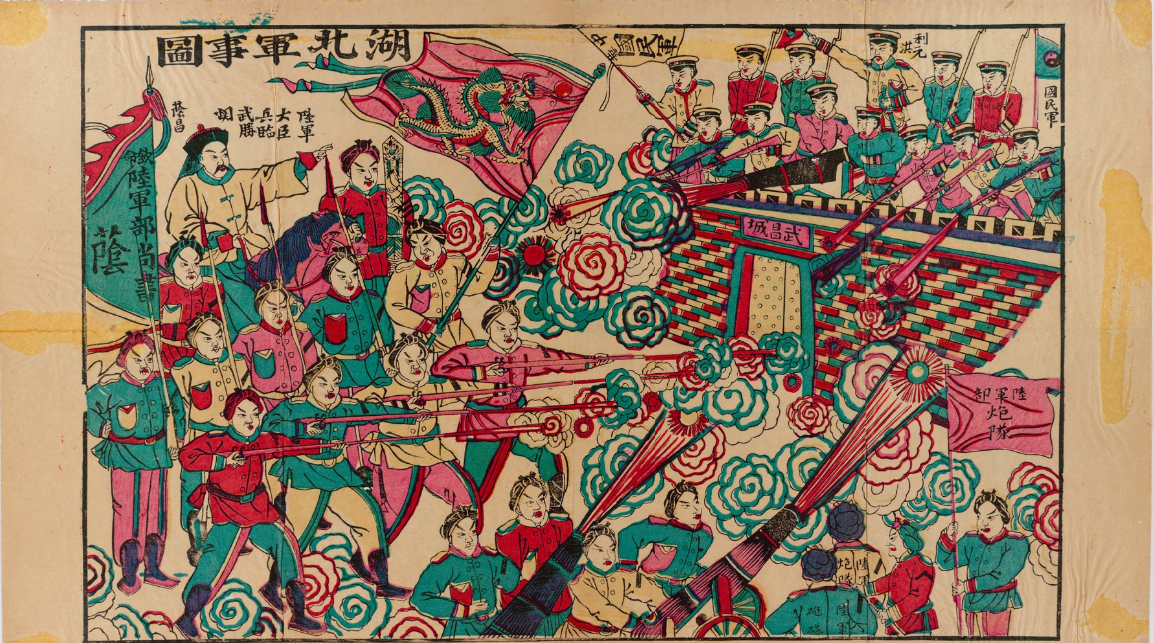

Looking back at the events at the time, historian Peter Zarrow has attempted to trace “the moment when the Wuchang Uprising became the ‘revolution’… that is when general opinion began to regard it as a movement that could overthrow the Qing and establish a new government.” Opinions were largely shaped, he writes, by Shanghai newspapers covering what Britannica Blog calls “a hastily and locally organized mutiny” that first began in one of the three areas that make up the city of Wuhan. In creating the narrative of events, news agencies “immediately printed illustrated sheets for a Chinese public avid for the latest news.” So writes the Princeton University Digital Library, who house a collection of 30 such prints, likely “based on upon artists’ imagination.”

News agency reports of the Wuchang Uprising and subsequent battles in cities across China “generally support the Revolution as a modernizing party, and hence some demonization of the enemy occurs in the prints, as was usual for propaganda prints of that and earlier periods.” What is notable is the degree to which broad themes of “modernity” and “nation” show up, creating a triumphant sense of unity that seems to have been exaggerated.

But this is the way propaganda works, in 1911 and today—“manufacturing consent,” to take Noam Chomsky’s phrase. It’s fascinating to see it work in images that seem so quaint to us today, but which, at the time, pushed forward a revolutionary break with over two thousand years of dynastic rule.

See many more of these images at Princeton’s Digital Library.

Related Content:

14,000 Free Images from the French Revolution Now Available Online

China: Traditions and Transformations (A Free Harvard Course)

Download 2,500 Beautiful Woodblock Prints and Drawings by Japanese Masters (1600–1915)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply