The ways that Othello, Aaron the Moor from Titus Andronicus, and Shylock from The Merchant of Venice—Shakespeare’s “explicitly racialized characters,” as George Washington University’s Ayanna Thompson puts it—have been interpreted over the centuries may have less to do with the author’s intentions and more with contemporary ideas about race, the actors cast in the roles, and the directorial choices made in a production. To a great degree, these characters have been played as though their identities were like the costumes put on by actors who darkened their faces or wore stereotypical markers of ethnic or religious Judaism (including “an obnoxiously large nose”).

Such portrayals risk turning complex characters into caricatures, validating much of what we might see as overt and implicit racism in the text. But there are those, Thompson says, who think such roles are actually “about racial impersonation.” Othello, for example, is “a role written by a white man, intended for a white actor in black makeup.”

For centuries, that is what most audiences fully expected to see. The tradition continued in Britain until the 19th century, when the Shakespearean color line, so to speak, was first crossed by Ira Aldridge, an American actor born in New York City in 1807.

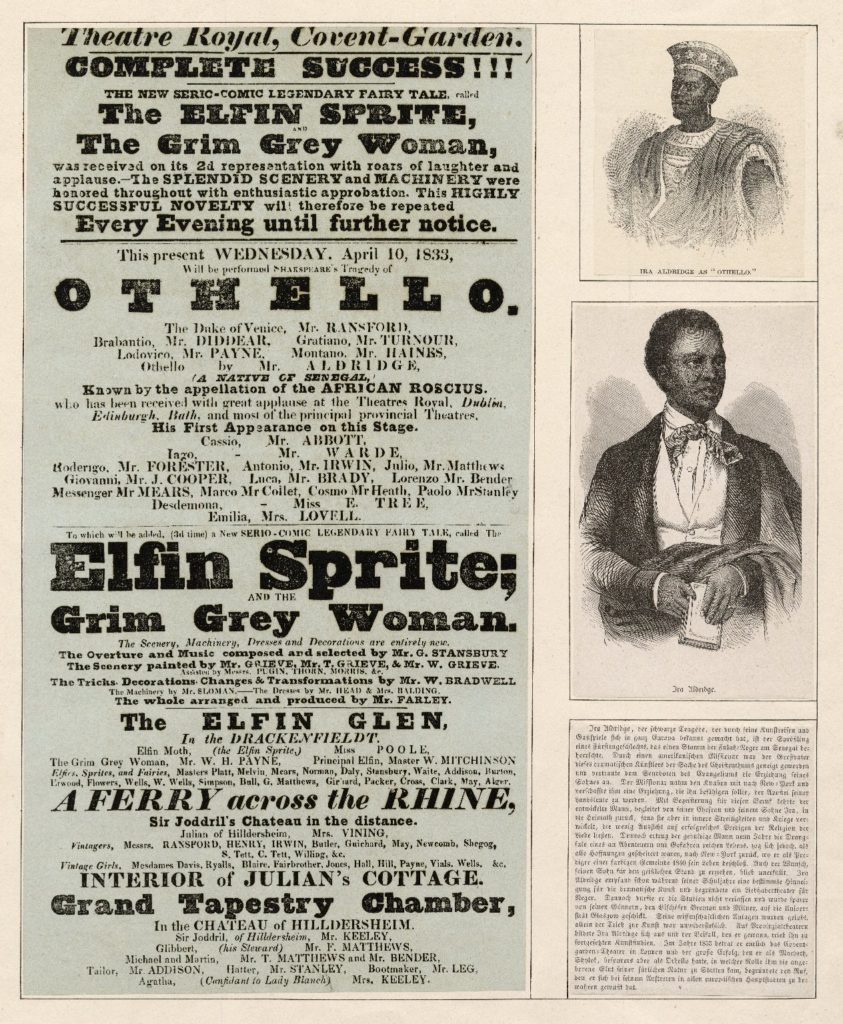

“Educated at the African Free School,” notes the Folger Shakespeare Library, Aldridge “was able to see Shakespeare plays at the Park Theatre and the African Grove Theatre.” He took on roles like Romeo with the African Company, but “New York was generally not a welcoming place for black actors… some white theatergoers even attempted to prevent black companies from performing Shakespeare at all.” As Tony Howard, an English professor at the University of Warwick, tells PRI, “he was beaten up in the streets.” And so Aldridge left for England in 1824, where he played Othello at the Theatre Royal, Covent-Garden, at only 17 years old, the first black actor to play a Shakespearean role in Britain.

He later began performing under the name Keene, “a homonym,” notes the site Black History 365, “for the then popular British actor, Edmund Kean.” Aldridge’s big break came after he met Kean and his son Charles, also an actor, in 1831, and both became supporters of his career. When the elder Kean collapsed onstage in 1833, then died, Aldridge took over his role as Othello at London’s Royalty Theatre in two performances. “Critics objected,” the Folger writes, “to his race, his youth, and his inexperience.” As Howard tells it, this characterization is a gross understatement:

There were those who said this is a very interesting and extraordinary young actor. And the fact that he’s a black actor makes it more interesting and fascinating. But for many people, it was an insult because this is still a society where there is a great deal of slavery in the British Empire. And in order to combat the idea of increasing abolition, performers like Ira had to be stopped. And so there was a great deal of violent aggression. Not physical violence this time, but violence in the press.

Some of that verbal violence included comparing Aldridge to “performing horses” and “performing dogs.” Many London critics saw his entry on the Shakespearean stage as an affront to English literary tradition. Performing the bard’s works was “a kind of violation,” Howard summarizes, “he has no right to do that, not even to play Othello.”

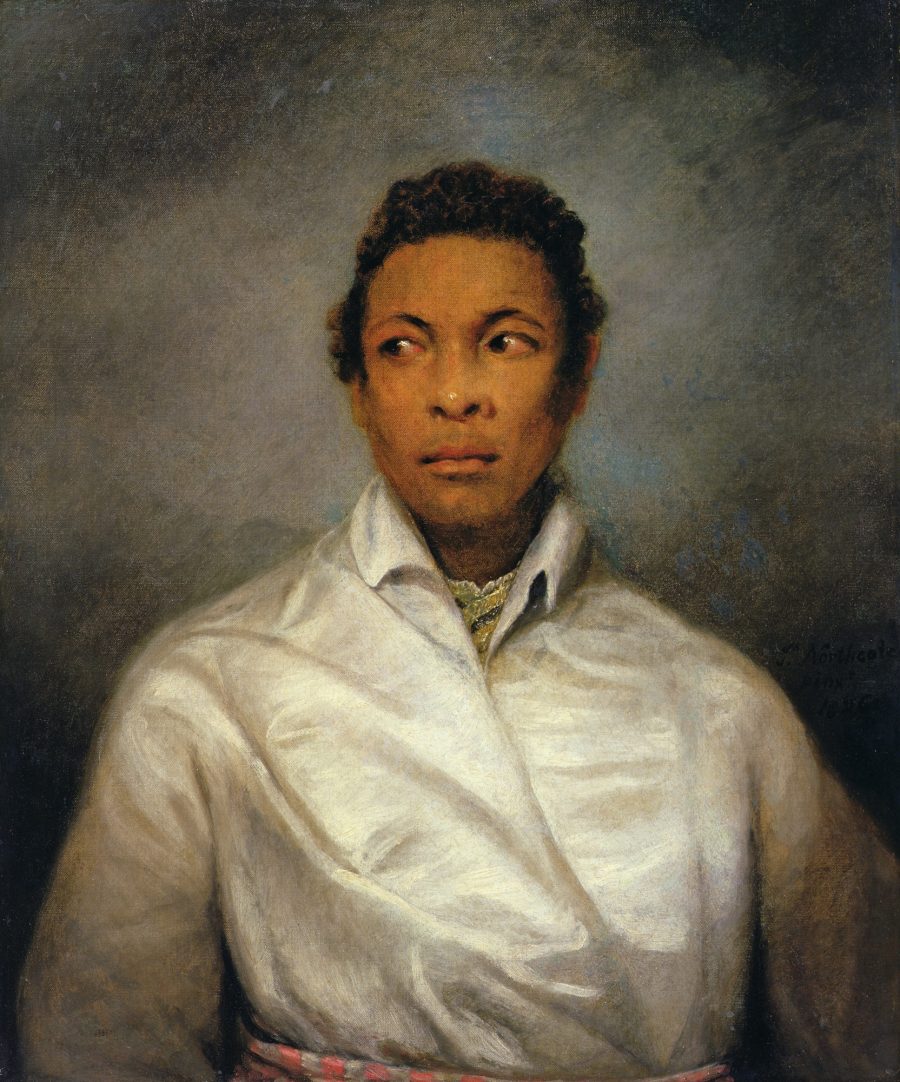

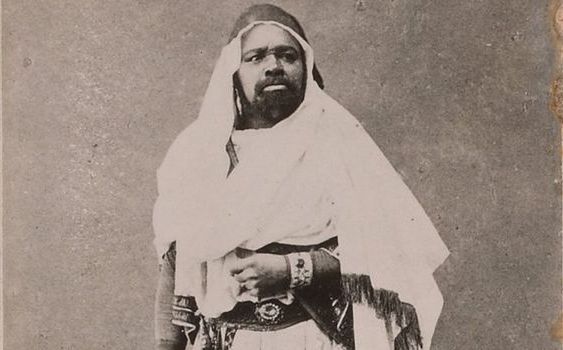

Photo via the Folger Library

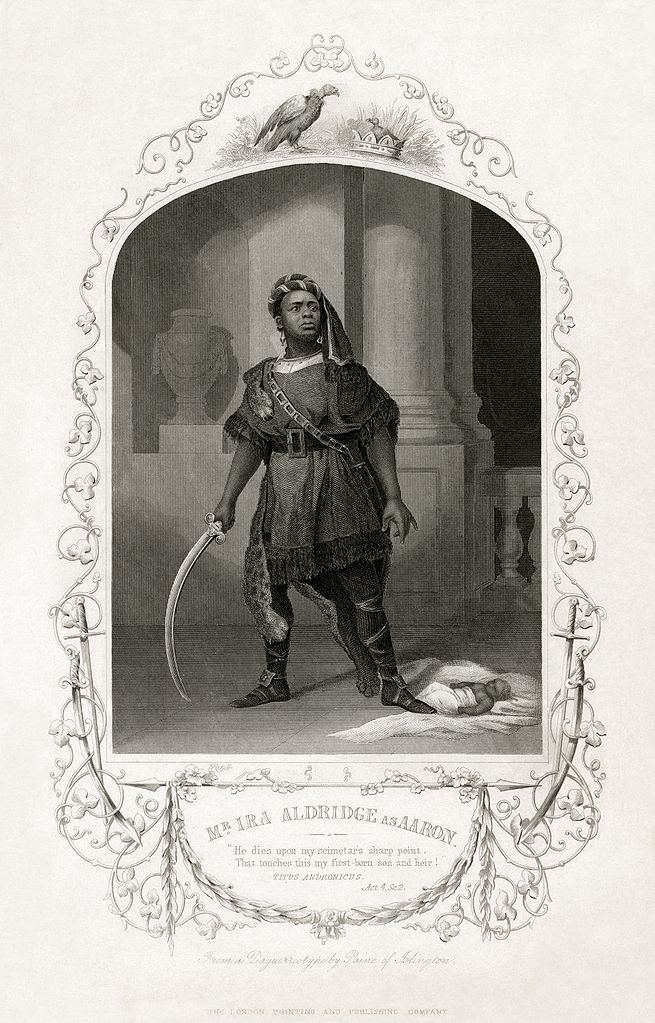

From his beginnings in Coventry to his experience in London, Aldridge made the once-blackface role his own, perhaps increasingly drawing “on his own experience and his own feeling.” He also portrayed Aaron in Titus, and as he persevered through negative press and prejudice, he took on other starring roles, including Richard III, Shylock, Iago, King Lear, and Macbeth. He “toured the English provinces extensively,” the BBC writes, “and stayed in Coventry for a few months, during which time he gave a number of speeches on the evils of slavery. When he left, people inspired by his speeches went to the county hall and petitioned for its abolition.”

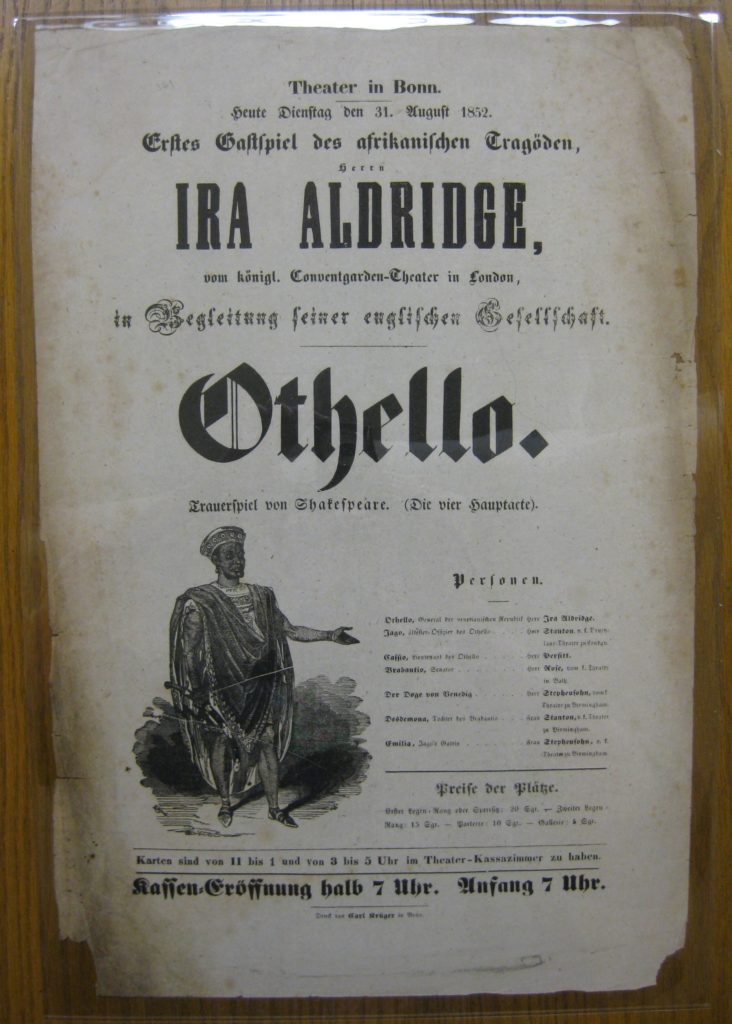

By the end of the 1840s, however, Aldridge felt he had gone as far as he could go in England and left to tour the Continent in what had become his signature role, Othello. While first touring with an English company, he “later began to work with local theater troupes,” the Folger writes, “performing in English while the rest of the cast would perform in German, Swedish, etc. Despite the language barrier, Aldridge’s performances in Europe were highly acclaimed, a testament to his acting skills.” (See a playbill further up from a Bonn performance.) After winning great fame in Europe and Russia, the actor returned in triumph to London in 1855, and this time was very well-received.

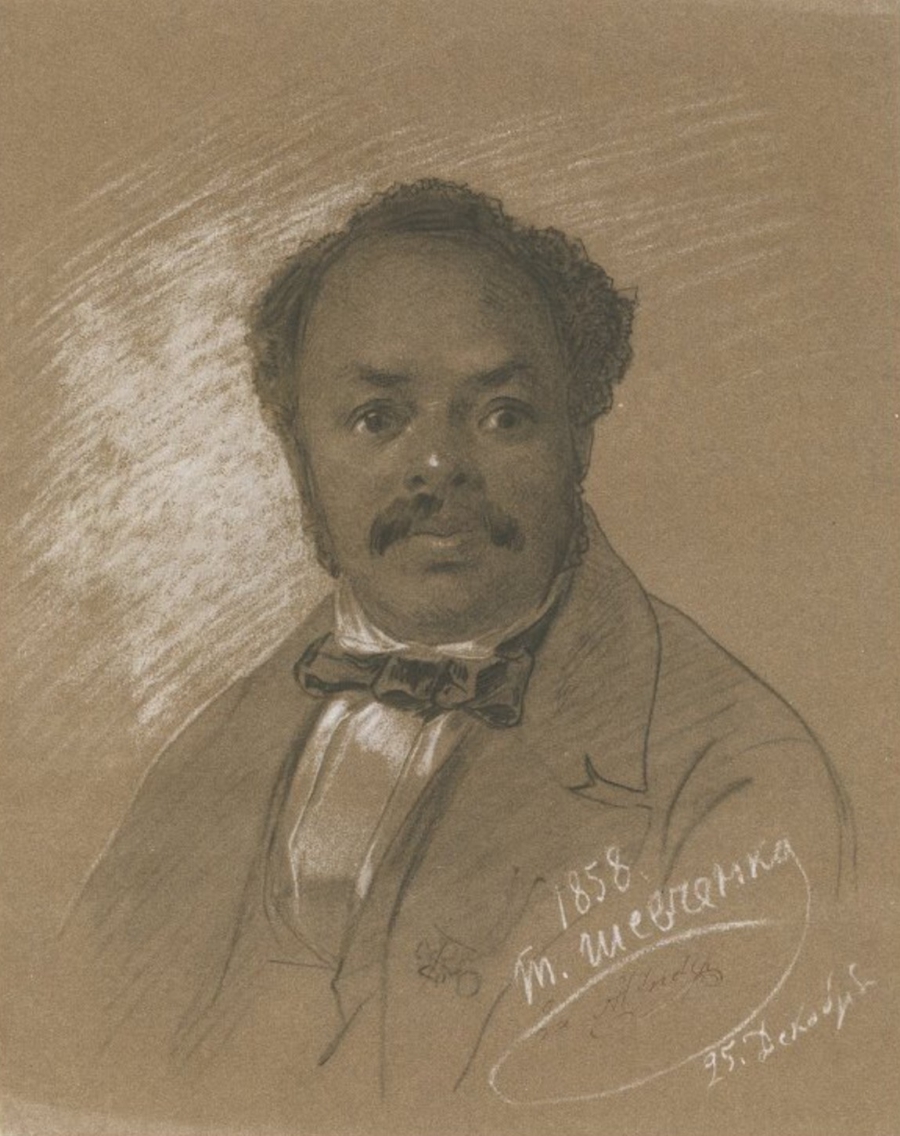

Aldridge died in 1867. And though he was the subject of many portraits of the period—like that by James Northcote at the top of the post, portraying the 19-year-old Aldridge as Othello, and this 1830 painting by Henry Perronet Briggs—he was “largely forgotten by theater historians.” (See him above in an 1858 drawing by Ukranian artist Taras Shevchenko.) But his legacy has been revived in recent years. Aldridge was the subject of two recent plays, Black Othello, by Cecilia Sidenbladh, and Red Velvet by Lolita Chakrabarti. And last year, he was honored in Coventry by a plaque on the site of the theater where he first achieved fame.

While he succeeded in becoming an all-around great Shakespearean actor, Aldridge’s legacy rests especially in the way he helped transform roles performed as “racial impersonation” for a few hundred years into the provenance of talented black actors who bring new depth, complexity, and authenticity to characters often played as stock ethnic villains. While white actors like Orson Welles and Lawrence Olivier continued to play Othello well into the 20th century, these days such casting can be seen as “ridiculous,” as Hugh Muir writes at The Guardian, especially if that actor “blacks up” for the role.

via the British Library

Related Content:

What Shakespeare’s English Sounded Like, and How We Know It

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

There’s some inaccurate information in here…