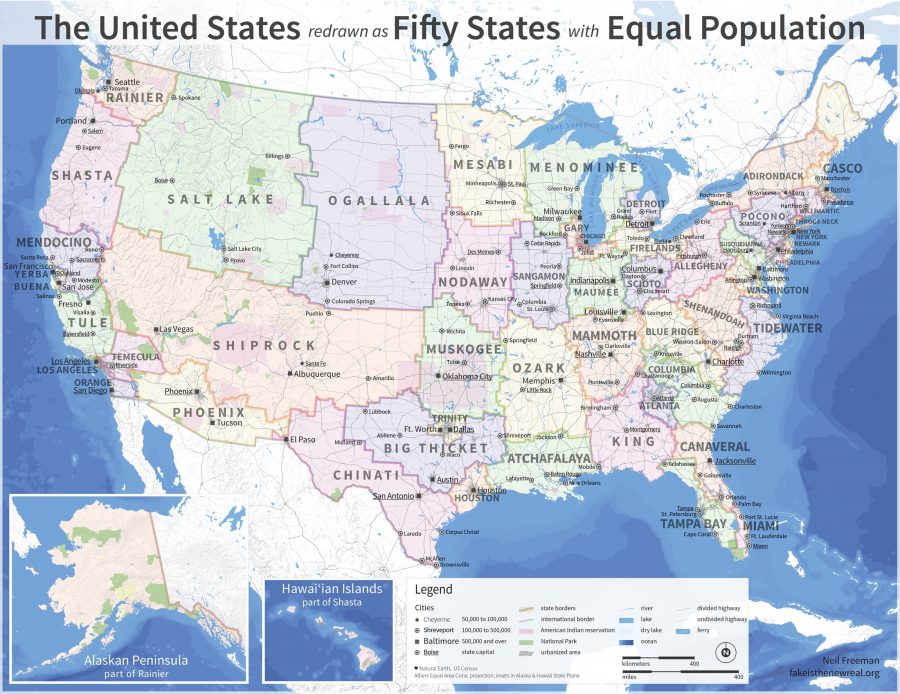

In the U.S., recent electoral events with which we’re all quite familiar have prompted one particular radical re-evaluation of the political system, among many others: we find everyone from high-profile Constitutional scholars to anonymous commenters engaged in debates about the necessity, or democratic legitimacy, of the Electoral College. While the debate may not be new, it has reached an urgent intensity, and happens to occur at a time when everything seems up for grabs. When Neil Freeman proposed redrawing state borders on his presciently-named design site Fake is the New Real back in 2012, he created the map above (view it in a larger format here) to evenly distribute the country’s population. He did so with the disclaimer, “this is an art project, not a serious proposal.”

The idea might get a more serious reception these days. Nonetheless, the inertia of tradition hasn’t lessened any. Not only is it totally unlikely that states would ever be redrawn and renamed, but the Electoral College is also a founding institution, emerging at the first Constitutional Convention when James Madison first proposed it in 1787. Since then, PBS’s Kamala Kelkar wrote on November 6th, 2016, “the Electoral College system has cost four candidates the race after they received the popular vote.” Two days later that number went up to five.

Still, whether one deems it necessary, superfluous, or deeply pernicious, it’s hardly controversial to note that this electing body comes from an era so unlike our own as to be unrecognizable. A time when, as some founders argued, writes Akhil Reed Amar at Time, “ordinary Americans across a vast continent [lacked] sufficient information to choose directly and intelligently among leading presidential candidates.” This might still be the case for various reasons. But putting aside manufactured filter bubbles and vast disinformation campaigns, most Americans now have instant access, if they want it, to more information than they know what to do with.

When we look at the primary sources, we find the actual reason for the Electoral College: slavery. Madison, notes Kelkar, “now known as the ‘Father of the Constitution,’” was a slaveholding Virginian who worried vocally that Northern states would have a decided advantage, since upwards of 40% of the population in Southern states consisted of enslaved people, who, of course, would not be casting votes. Madison’s proposition included the infamous and dehumanizing “three-fifths compromise,” which historian Paul Finkelman argues enabled Thomas Jefferson to win over John Adams in 1800.

Despite this history, most people are taught that the system arose solely to “balance the interests,” Amar writes, “of high-population and low-population states.” This sounds like a politically neutral intention. But Freeman doesn’t question the legitimacy of the Electoral College, calling it “a time-honored, logical system” that he thinks should be preserved. And yet, he writes, “it’s obvious that reforms are needed.”

“The fundamental problem of the electoral college,” Freeman writes, “is that the states of the United States are too disparate in size and influence. The largest state is 66 times as populous as the smallest and has 18 times as many electoral votes. This increases the chance for Electoral College results that don’t match the popular vote.” This is hardly the only issue. But is Freeman’s proposal a more stable solution to major flaws in U.S. national elections than simply scrapping the Electoral College altogether? He makes the following argument, in a series of bullet-pointed advantages. His map:

- Preserves the historic structure and function of the Electoral College.

- Ends the over-representation of small states and under-representation of large states in presidential voting and in the US Senate by eliminating small and large states.

- Political boundaries more closely follow economic patterns, since many states are more centered on one or two metro areas.

- Ends varying representation in the House. Currently, the population of House districts ranges from 528,000 to 924,000. After this reform, every House seat would represent districts of the same size. (Since the current size of the House isn’t divisible by 50, the numbers of seats should be increased to 450 or 500.)

- States could be redistricted after each census — just like House seats are distributed now.

Freeman based the map–featuring new states like “Mesabi,” “Ogallala,” “Big Thicket,” “Chinati,” and “King”–on data from the 2010 Census, which, incidentally, actually did change the distribution of electors in 2012. The Census “records a population of 308,745,538 for the United States,” he notes, “which this map divides into 50 states, each with a population of about 6,175,000.”

He does seem to downplay the disadvantages, listing only two concerns about duplicated county names and a “shift in state laws and procedures.” Freeman doesn’t mention the high likelihood of civil war or widespread social unrest if such a massive redistribution of the country’s state populations were ever attempted. Given the examples of pitched legal battle fought daily over congressional redistricting of gerrymandered states, it’s also probable nothing like this plan would ever make it through the courts. Considered as an “art project” or thought experiment in civics, however, who knows? It just might work….

via Mental Floss

Related Content:

Sal Khan & the Muppets’ Grover Explain the Electoral College

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

It is worth remembering that the Founders were very much against pure democracy. They created a federal republic which includes many kinds of checks on majority rule, which they rightly understood could be very dangerous. Their system has served well for over two hundred years, and thus we ought to be very careful about tinkering with it.

Your point regarding the “dehumanizing” effect of the three-fifths compromise misses the mark. While slavery itself — a condition that was the norm globally until relatively recently in history — was dehumanizing, the three-fifths compromise was not. It was the southern states, the advocates of the slave system, that wanted slaves to be fully counted to increase southern state representation in Congress. This would have had the effect of perpetuating slavery by increasing the political clout of the southern states. By contrast, the northern states did not want slaves to be counted at all in determining state population and thus congressional representation. The northern states’ position, therefore, would have weakened the institution of slavery. Thus, this post has it backwards — the most dehumanizing result would have been to fully count the slave population and thus increase the political power of the advocates of slavery.

Thanks for sharing this. It gave me a lot to think about, and to share with my geography students and other readers.

http://environmentalgeography.blogspot.com/2018/03/the-fraught-fifty.html