A deep appreciation for profanity may rate high as a mark of a sophistication and authenticity. Cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker has made the neuroscience of swearing an object of study; legendary comic actor, writer, and “language enthusiast” Stephen Fry declares the practice a fine art; studies show that those who swear may be more honest than those who don’t; and if you have any doubt about how much swearing contributes to the literary history of the English language, just do a search on Shakespeare’s many profane insults, so rich and varied as to constitute a genre all their own.

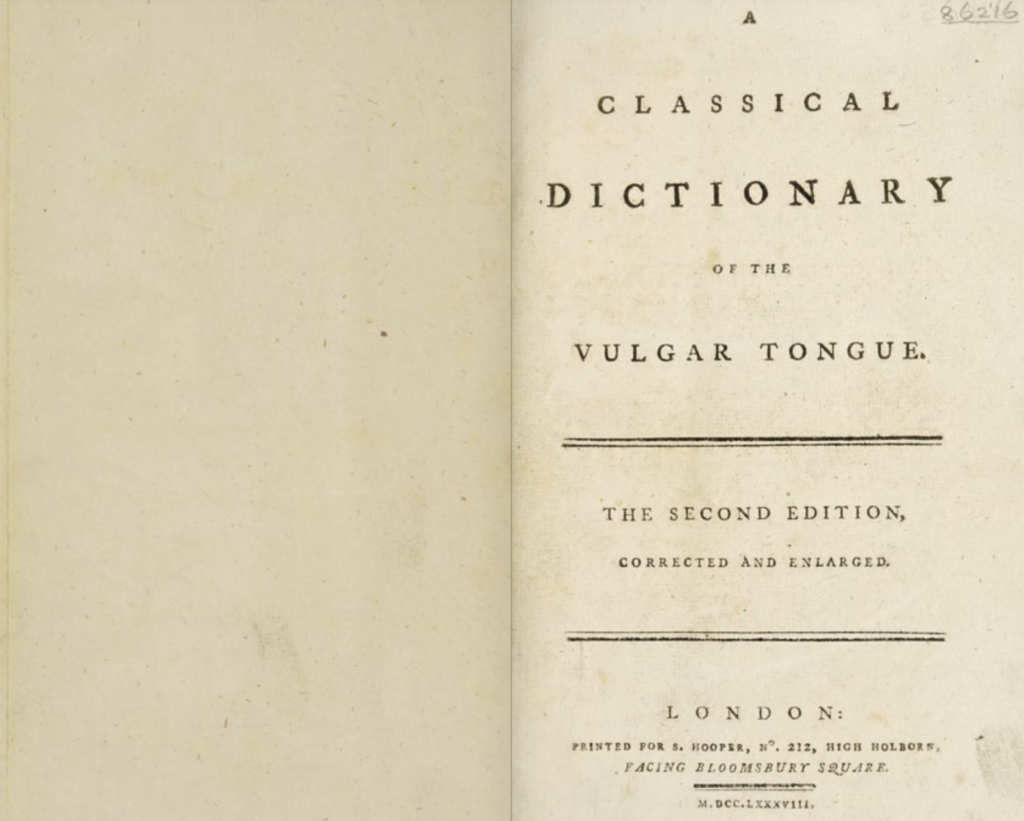

Not all vulgar speech is considered “swear words,” referencing sex acts and bodily functions, but many a critic and lexicographer has nonetheless decided that slang, obscene or otherwise, doesn’t belong in polite company with formal diction. Samuel Johnson, the esteemed 18th-century essayist, poet, and compiler of the 1755 Dictionary of the English Language deemed slang “unfit for his learned tome,” writes The Public Domain Review. So, enter Francis Grose to correct the error thirty years later with his Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, a “compendium of slang” chock full of hilarious idioms of every kind.

There is the bawdy (“Sugar stick—the virile member”), the scatological (“Cackling farts—eggs”), the oddly obscure (“Kittle pitchering—to disrupt the flow of a ‘troublesome teller of long stories’ by constantly questioning and contradicting unimportant details, especially at the start”). Puns make their inevitable way in (“Just-ass—a punning name for justice [judge]”), as of course do comic images for body parts (“Tallywags/Whirligigs—testicles”). Much of this Early Modern English slang sounds to American ears just as colorfully askew as contemporary English slang does (“Dog booby—an awkward lout”; “Captain queernabs—a shabby ill-dressed fellow”).

Grose, compiler of the dictionary, “was not one for library work” and preferred to collect his specimens in the field where slang lives and breathes—the streets, pubs, and houses of ill-repute. “Supported by his trusty assist Tom Cocking [your joke here],” Grose “cruised the watering holes of Covent Garden and the East End, eating, boozing, and listening. He took pleasure in hearing his name punningly connected to his rotund frame. And he produced a book brimming with Falstaffian life.” Very much a Shakespearean bon vivant, Grose appears as something of a ribald doppelganger of the rotund, yet moralistic and often scowling Dr. Johnson. (See his portrait here.)

The so-called “long 18th-Century”—a period lasting from the restoration of the Monarchy after the English Civil War to around the French Revolution—presents a tradition of lewd witticism, from the poetry of John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester, to Jonathan Swift’s “The Lady’s Dressing Room,” to the sordid fantasies of the Marquis de Sade. Such pornographic humor and rude earthiness offered a counterweight to heady Enlightenment philosophy, just as Shakespeare’s insults provide needed comic relief for his bloody tragedies. Grose’s dictionary can be seen as adding needed comic local color to the many serious dictionaries and studies of language that emerged in the 1700s.

But A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue is also an important academic resource all its own, and “would strongly influence later dictionaries of this kind,” notes the British Library—those like J. Redding Ware’s 1909 Passing English of the Victorian Era: A Dictionary of Heterodox English, Slang, and Phrase. We can see in Grose’s work how many slang words and phrases still in common use today—like “baker’s dozen,” “gift of the gab,” “birds of a feather,” “birthday suit,” and “kick the bucket”—were just as current well over 200 years ago. And we get a very vivid sense of the world in which Grose moved in the many metaphors employed, most involving food and drink. (A “butcher’s dog,” for example, refers to someone who “lies by the beef without touching it; a simile often applicable to married men.”)

But we needn’t worry too much about scholarly uses for Grose’s work. Instead, we might find ourselves motivated to do as he did, hit the streets and the bars, and maybe bring back into circulation such locutions as “Betwattled” (surprised, confounded, out of one’s senses), “Chimping merry” (exhilarated with liquor), or, perhaps my favorite so far, “Dicked in the nob” (silly, crazed).

Page through Grose’s dictionary above or read it in a larger format (and/or download as a PDF or ePub) at the Internet Archive.

Related Content:

The Very First Written Use of the F Word in English (1528)

People Who Swear Are More Honest Than Those Who Don’t, Finds a New University Study

Stephen Fry, Language Enthusiast, Defends The “Unnecessary” Art Of Swearing

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply