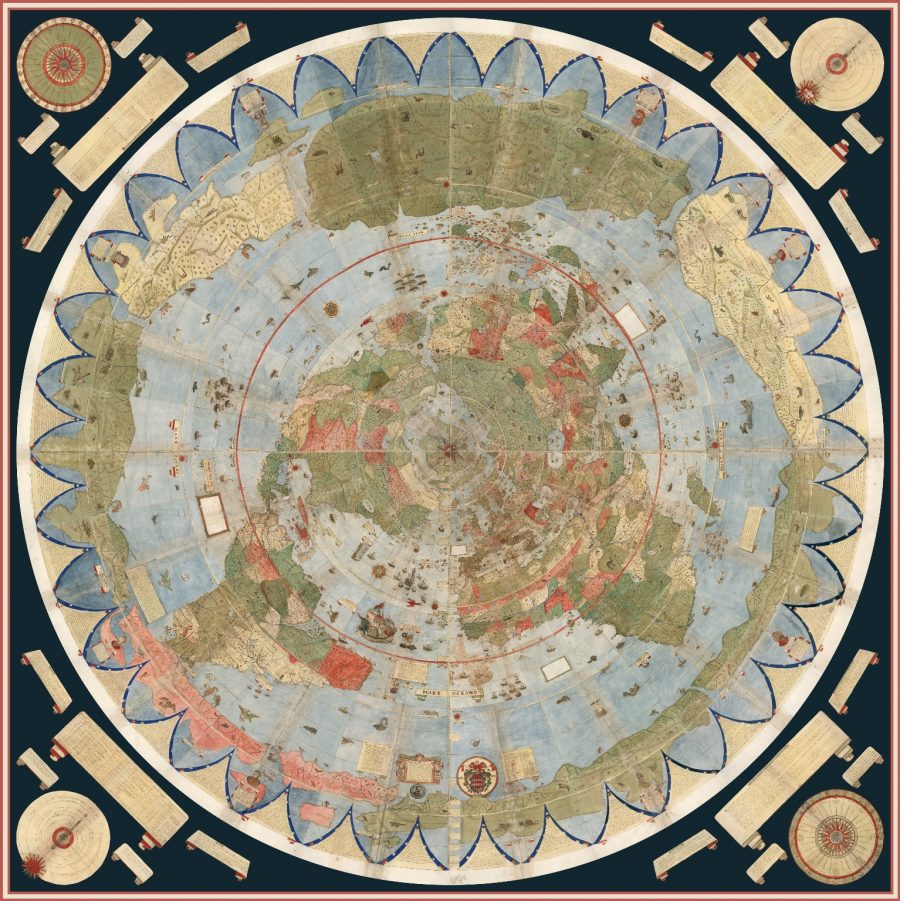

We in the early 21st century can call up detailed maps of almost any place on Earth with little more effort than typing its name. Most of us can dimly recall a time when it wasn’t quite so easy, but imagine trying to satisfy your geographical curiosity in not just decades but centuries past. For the 16th-century Milanese gentleman scholar Urbano Monte, figuring out what the whole world looked like turned into an enormous project, in terms of both effort and sheer size. In 1587, he created his “planisphere” map as a 60-page manuscript, and only now have researchers assembled it into a single piece, ten feet square, the largest known early map of the world. View it above, or in a larger format here.

“Monte appears to have been quite geo-savvy for his day,” writes National Geographic’s Greg Miller, noting that “he included recent discoveries of his time, such as the islands of Tierra del Fuego at the tip of South America, first sighted by the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan in 1520,” as well as an uncommonly detailed Japan based on information gathered from a visit with the first official Japanese delegation to Europe in 1585.

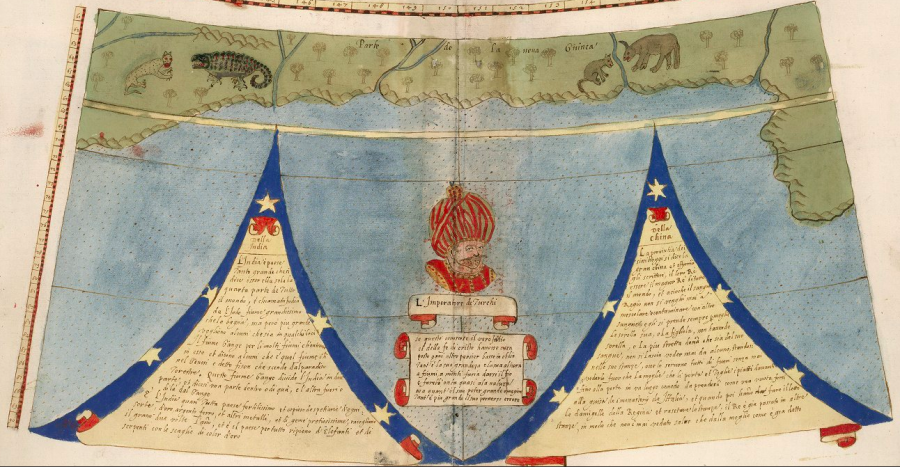

And in accordance with the mapmaking style of the time, he got more fanciful in the less-understood spaces: “Animals roam the land, and his oceans teem with ships and monsters. King Philip II of Spain rides what looks like a floating throne off the coast of South America, a nod to Spanish prominence on the high seas.”

“Monte’s map reminds us of why historical maps are so important as primary resources,” says Stanford University’s David Rumsey Map Collection, which holds one of only three extant versions of the map and which conducted the digital project of scanning each of its pages and assembling them into a whole. Not only does its then-unusual (but now long standard in aviation) north polar azimuthal projection show Monte’s use of “the advanced scientific ideas of his time,” but the “the artistry in drawing and decorating the map embodies design at the highest level; and the view of the world then gives us a deep historical resource with the listing of places, the shape of spaces, and the commentary interwoven into the map.”

You can see/download Monte’s planisphere in detail at the David Rumsey Map Collection, both as a collection of individual pages and as a fully assembled world map. There you can also read, in PDF form, cartographic historian Dr. Katherine Parker’s “A Mind at Work: Urbano Monte’s 60-Sheet Manuscript World Map.” And to bring this marvel of 16th-century cartography around to a connection with a marvel of 21st-century cartography, they’ve also taken Monte’s planisphere and made it into a three-dimensional model in Google Earth, a mapping tool that Monte could scarcely have imagined — even though, as a close look at his work reveals, he certainly didn’t lack imagination.

via Hyperallergic

Related Content:

The History of Cartography, the “Most Ambitious Overview of Map Making Ever,” Now Free Online

Japanese Designers May Have Created the Most Accurate Map of Our World: See the AuthaGraph

Watch the History of the World Unfold on an Animated Map: From 200,000 BCE to Today

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply