The Aristotelian notion of “man” as a “rational animal” has seen its share of detractors, from the Cynics to Bertrand Russell to nearly the whole of Poststructuralist thought. Leave it up to Oscar Wilde to compress the debate between intellect and passion into a pithy aphorism: “Man is a rational animal who always loses his temper when he is called upon to act in accordance with the dictates of reason.”

We no longer need clever verbal barbs to refute too-optimistic assessments of human behavior. Economics is catching up: we have the language of neuroscience and psychology, which consistently tells us that humans decidedly do not behave rationally very often, but are driven by bias and biology in inexplicable ways. And for over a hundred years now, we’ve known that the clockwork Newtonian view of the physical universe turns out be a much messier and indeterminate affair, as does the universe of the human mind.

Why, then, has so much economic theory operated with a kind of dogged Aristotelianism, insisting that the units of capitalist society, the workers, managers, investors, consumers, owners, renters, speculators, etc. behave in predictable ways? We have case after case showing that intelligence and critical reasoning often have little to do with success or failure in the market. In such cases, however, one often hears the “madness of crowds” or other cliches invoked as an explanation.

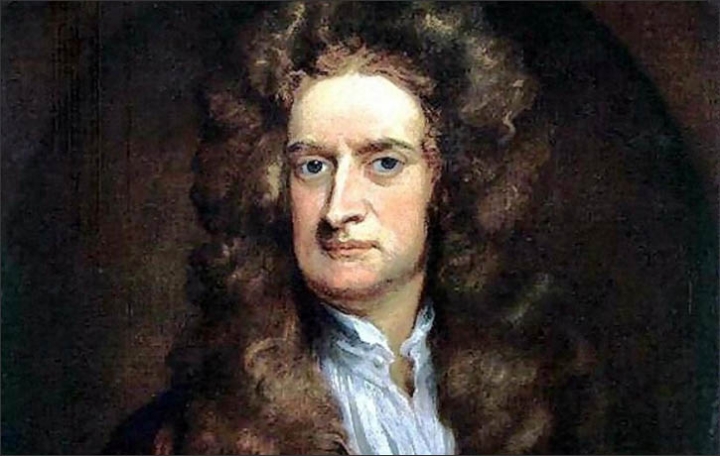

To illustrate, market reporters and business writers have seized upon the story of Isaac Newton’s spectacular rise and fall in the so-called “South Sea Bubble” of 1720. We find the story in Benjamin Graham’s 1949 classic The Intelligent Investor, a widely-read book that attributes the irrationality of market systems to an anthropomorphic entity named “Mr. Market.”

Graham writes,

Back in the spring of 1720, Sir Isaac Newton owned shares in the South Sea Company, the hottest stock in England. Sensing that the market was getting out of hand, the great physicist muttered that he ‘could calculate the motions of the heavenly bodies, but not the madness of the people.’ Newton dumped his South Sea shares, pocketing a 100% profit totaling £7,000. But just months later, swept up in the wild enthusiasm of the market, Newton jumped back in at a much higher price — and lost £20,000 (or more than $3 million in [2002–2003’s] money. For the rest of his life, he forbade anyone to speak the words ‘South Sea’ in his presence.

The quotation in bold may or may not have been uttered by Newton, but the events Graham describes did indeed happen. As the Wall Street Journal’s Jason Zwieg relates, University of Minnesota professor Andrew Odlyzko found that “Newton had shifted from a prudent investor with his money spread across several securities to a speculator who had plunged essentially all of his capital into a single stock. The great scientist was chasing hot performance as desperately as a day trader in 1999 or many bitcoin buyers in 2017.” (Odlyzko estimates Newton’s losses closer to $4 million.) Perhaps it was not a metaphorical “Mr. Market” who cost Newton up to 77% “on his worst purchases,” nor was it widespread “wild enthusiasm”—the mass movement of passion that Enlightenment philosophers so feared.

Perhaps it was Newton himself who, Elena Holodny writes at Business Insider, “let his emotions get the best of him, and got swayed by the irrationality of the crowd.” Maybe it’s more accurate to say Newton succumbed to greed when the bubble expanded. “Throughout history,” Barbara Kollmeyer writes at Market Watch in her interview with author Richard Dale, “people—especially those at the top rung of society—have been greedy and gullible participants in financial bubbles. And Sir Isaac Newton was only human, after all.” (How many at the top rung of society fell prey to Bernie Madoff’s schemes? And a century before the South Sea Bubble, hundreds of wealthy investors lost their shirts in the Dutch Tulip Bulb craze.)

Some business writers, like investment editor Richard Evans at The Telegraph, recommend a calculable formula to avoid losing a fortune in bubbles, advice that takes rational agency for granted. Perhaps it should not. In addition to citing the contagion of crowds, nearly every discussion of Newton’s folly allows that a failure of emotional discipline played a significant role. Benjamin Graham invokes another Aristotelian notion—the idea that “character” counts as much or more than intelligence when it comes to investing. “The investor’s chief problem,” he writes, “and even his worst enemy—is likely to be himself.”

Far fewer commenters note that the South Sea venture was itself a failure of character from its inception. The company had secured an exclusive monopoly on trade with South America; much of that trade involved selling slaves. It is also the case that the company artificially inflated its stock prices, and colluded with several MPs in insider trading schemes. The so-called “Bubble Act” of Parliament in 1720, presumably passed to prevent crashes like the one that devastated Newton, turned out to be corporate giveaway. The terms of the act had been dictated by the South Sea Company in order to prevent other companies from poaching their investors. Although these circumstances are well-known to economic historians, they rarely make their way into commentary on Newton’s great loss.

Economists instead tend to blame abstractions for economic events like the South Sea Bubble, or they blame the overreaching profit-seeking of investors, and maybe for good reason. The other explanations haunt the margins: the inherently exploitative nature of most forms of corporate capitalism, and the corruption and collusion between the state and private enterprise that inhibits fair competition and makes it impossible for investors to evaluate the situation transparently. For all of his scientific and mathematical genius, Isaac Newton was no exception—he was just as subject to irrational greed as the next investor, and to the predatory machinations of “market forces.”

Related Content:

In 1704, Isaac Newton Predicts the World Will End in 2060

Isaac Newton Creates a List of His 57 Sins (Circa 1662)

Sir Isaac Newton’s Papers & Annotated Principia Go Digital

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply