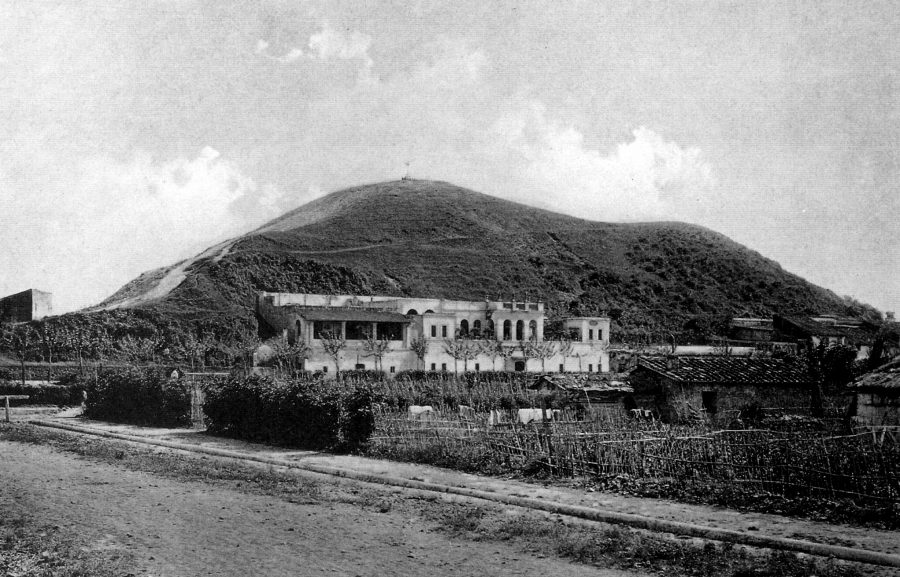

Image by patrimoni gencat, via Flickr Commons

It may be one of the more curious manmade garbage piles on our planet. Located in Rome, and dating back to 140 A.D., Monte Testaccio rises 150 feet high. It covers some 220,000 square feet. And it’s made almost entirely of 53 million shattered amphorae–that is, Roman jugs used to transport olive oil during ancient times. How did the remnants of so many amphorae end up here? The web site Olive Oil Times offers this explanation:

Firstly, the site of the mound on the east bank of the Tiber is located near the Horrea Galbae – a huge complex of state controlled warehouses for the public grain supply as well as wine, food and building materials. As ships came from abroad bearing the olive oil supplies, the transport amphorae were decanted into smaller containers and the used vessels discarded nearby.

There’s a reason for this: Due to the clay utilized to make the amphorae not being lined with a glaze, after transportation of olive oil, the amphorae could not be re-used because the oil created a rancid odour within the fabric of the clay.

You might consider this Roman garbage dump an historical oddity. But as they say, one man’s trash is another man’s treasure. And according to Archaeology (a website of the Archaeological Institute of America) Monte Testaccio promises to reveal much about the inner-workings of the Roman economy. They write:

As the modern global economy depends on light sweet crude, so too the ancient Romans depended on oil—olive oil. And for more than 250 years, from at least the first century A.D., an enormous number of amphoras filled with olive oil came by ship from the Roman provinces into the city itself, where they were unloaded, emptied, and then taken to Monte Testaccio and thrown away. In the absence of written records or literature on the subject, studying these amphoras is the best way to answer some of the most vexing questions concerning the Roman economy—How did it operate? How much control did the emperor exert over it? Which sectors were supported by the state and which operated in a free market environment or in the private sector?

For historians, these are important questions, and they’re precisely the questions being asked by University of Barcelona professor, José Remesa, who notes, “There’s no other place where you can study economic history, food production and distribution, and how the state controlled the transport of a product.”

Above get a distant view of Monte Testaccio. Below get a close up view of the amphorae shards themselves.

Image by Alex, via Flickr Commons

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

The Oldest Unopened Bottle of Wine in the World (Circa 350 AD)

How to Bake Ancient Roman Bread Dating Back to 79 AD: A Video Primer

Rome Reborn: Take a Virtual Tour of Ancient Rome, Circa 320 C.E.

Leave a Reply