We all know the name Marie Curie—or at least I hope we do. But for far too many people, that’s where their knowledge of women in science ends. Which means that thousands of young boys and girls who read about Isaac Newton and Louis Pasteur never also learn the story of Caroline Herschel (1750–1848), the first woman to discover a comet, publish with the Royal Society, and receive a salary for scientific work—as the assistant to the king’s astronomer, her brother, in 19th century England. Herschel discovered and catalogued new nebulae and star clusters; received a gold medal from the Royal Astronomical Society; and she and her brother William “increased the number of known star clusters,” writes the Smithsonian, “from 100 to 2,500.” And yet, she remains almost totally obscure.

Open a math or physics textbook and you may not come across the name Emmy Noether (1882–1935), either, despite the fact that she “proved two theorems,” the San Diego Supercomputer Center (SDSC) notes, “that were basic for both general relativity and elementary particle physics. One is still known as ‘Noether’s Theorem.’”

Noether fought hard for recognition in life. She received her Ph.D. in mathematics from the University of Göttingen in 1907, and she eventually surpassed her scientist father and brothers. But at first, she could only secure work at the Mathematical Institute of Erlangen in a position without title or pay. And despite her brilliance, she was only allowed to teach at Göttingen University as the assistant to David Hilbert, also without a salary.

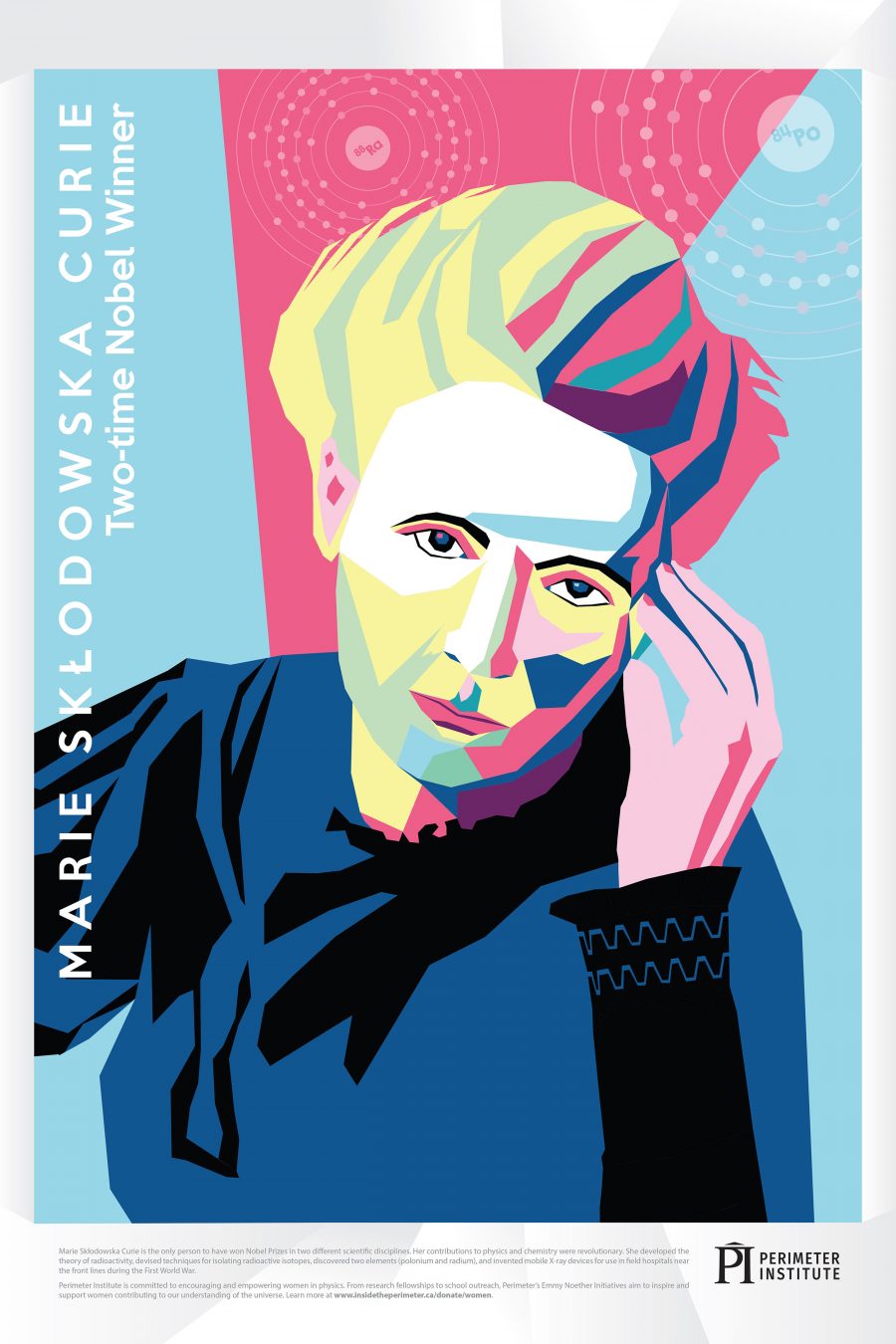

Noether suffered discrimination in Germany “owing not only to prejudices against women, but also because she was a Jew, a Social Democrat, and a pacifist.” Other prominent women in scientific history have encountered similarly intersecting forms of discrimination, and continue to do so. Much has changed since the times of Herschel and of Noether, but “there is much work to be done,” writes Eamon O’Flynn of the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics. “Part of making positive change includes celebrating the contributions women have made to science, especially those women overlooked in their time.” For this reason, the Perimeter Institute has created a poster series, called “Forces of Nature,” for “classrooms, dorm rooms, living rooms, offices, and physics departments.”

The posters feature Curie, Noether, computing pioneer Ada Lovelace, stellar astronomer Annie Jump Cannon, and “first lady of physics” Chien-Shiung Wu. Should you want one or all of these as high-resolution images printable up to 24”x36”, visit the Perimeter Institute’s site and follow the links to fill out a short form. Whether you’re a parent, teacher, or mentor—these striking pop art posters seem like an excellent way to get a conversation about women in science started. Follow up with the Smithsonian’s “Ten Historic Female Scientists You Should Know,” SDSC’s Women in Science project, Rachel Ignotofsky’s Women in Science: 50 Fearless Pioneers Who Changed the World, and—for a contemporary view of women working in every possible STEM field—the Association for Women in Science.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply