Whether in the tanks into which we gaze at the aquarium or the CGI-intensive wildlife-based gagfests at which we gaze in the theater, most of us in the 21st century have seen more than a few funny fish. Eighteenth-century Europeans couldn’t have said the same. The great majority passed their entire lives without so much as a glance at the form of even one live exotic creature of the deep, and most of those who have a sense of what such a sight looked like probably got it from an illustration. But even so, some of the illustrated fish of the day must have proven unforgettable, especially the ones in Louis Renard’s Poissons, Ecrevisses et Crabes.

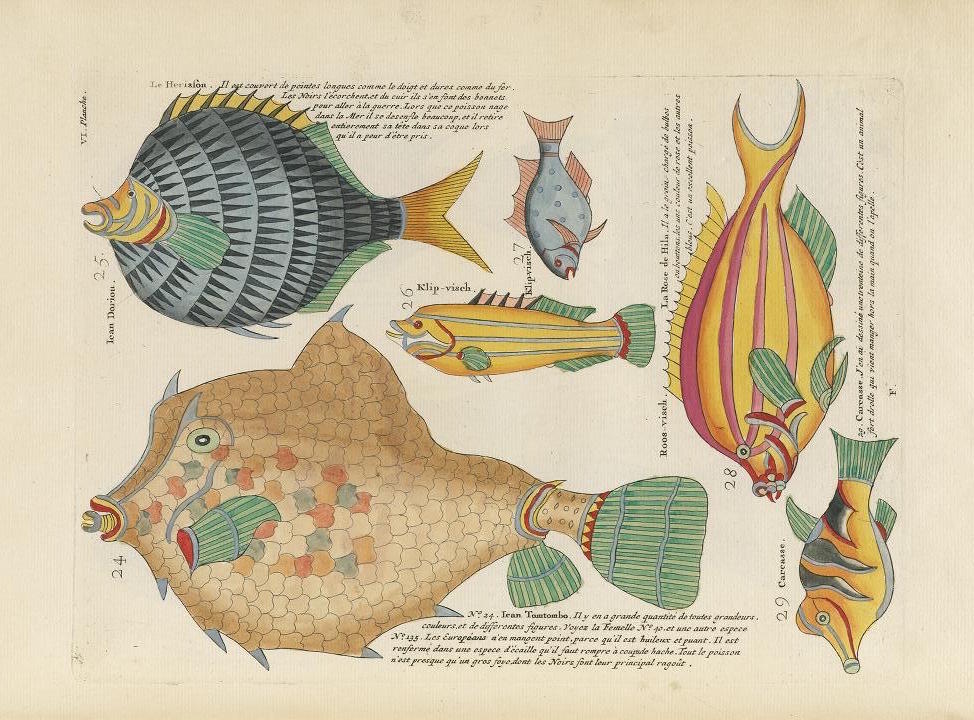

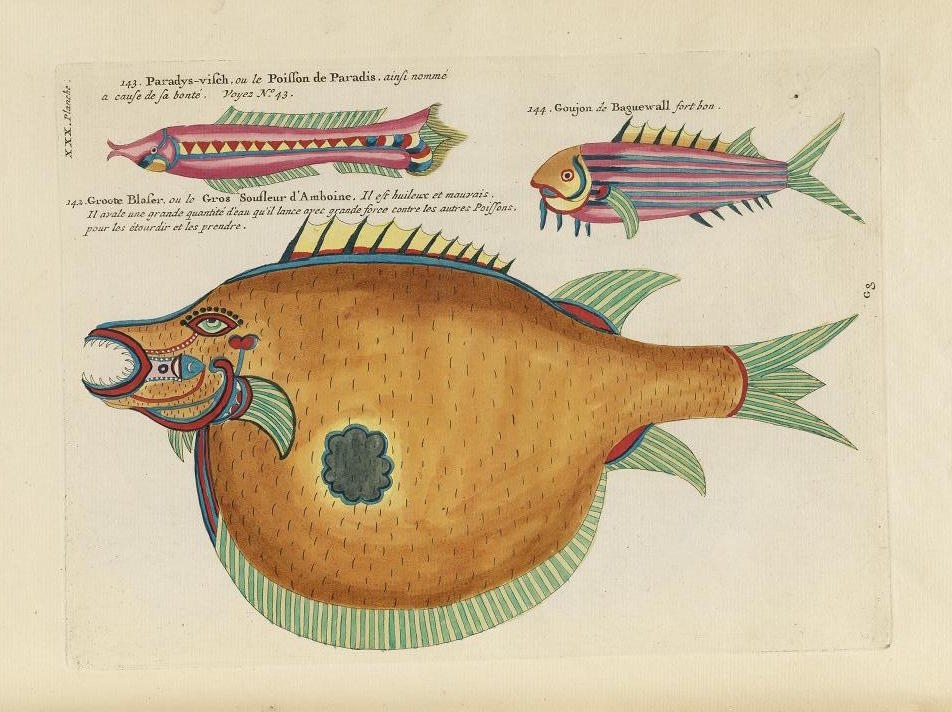

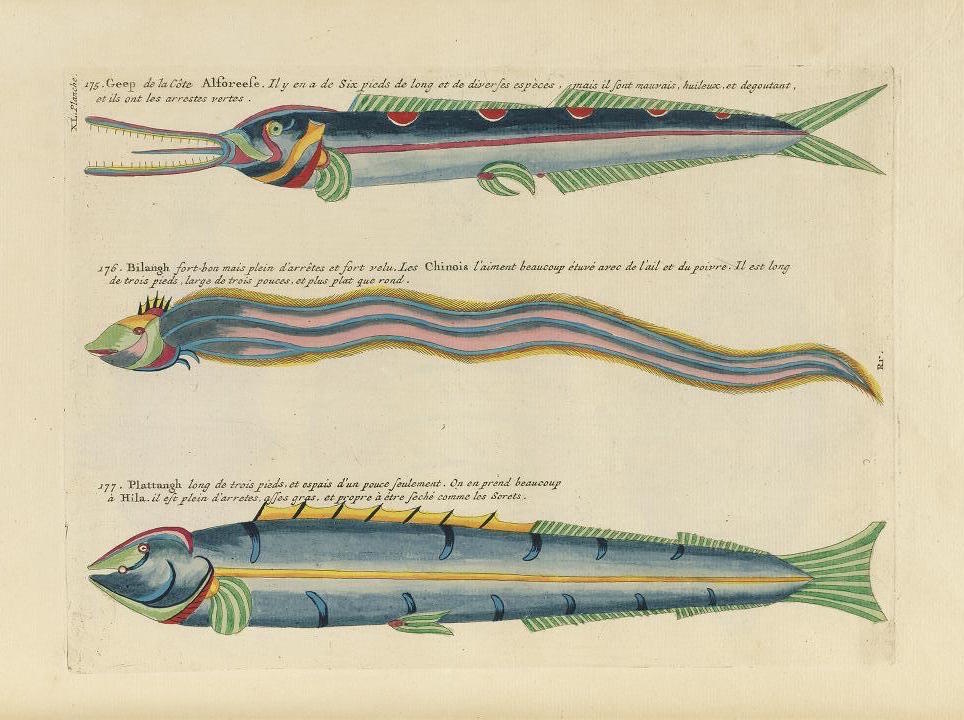

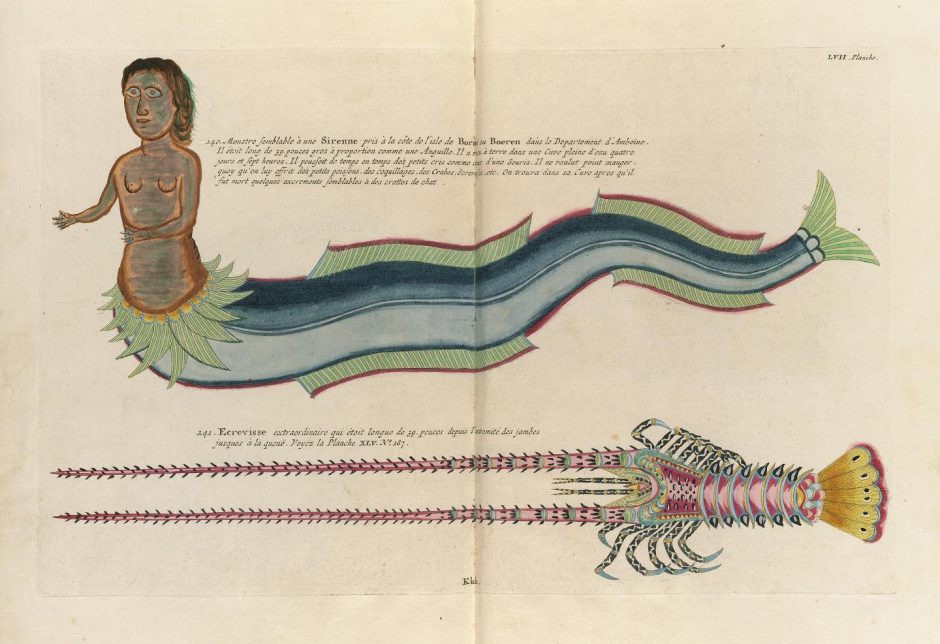

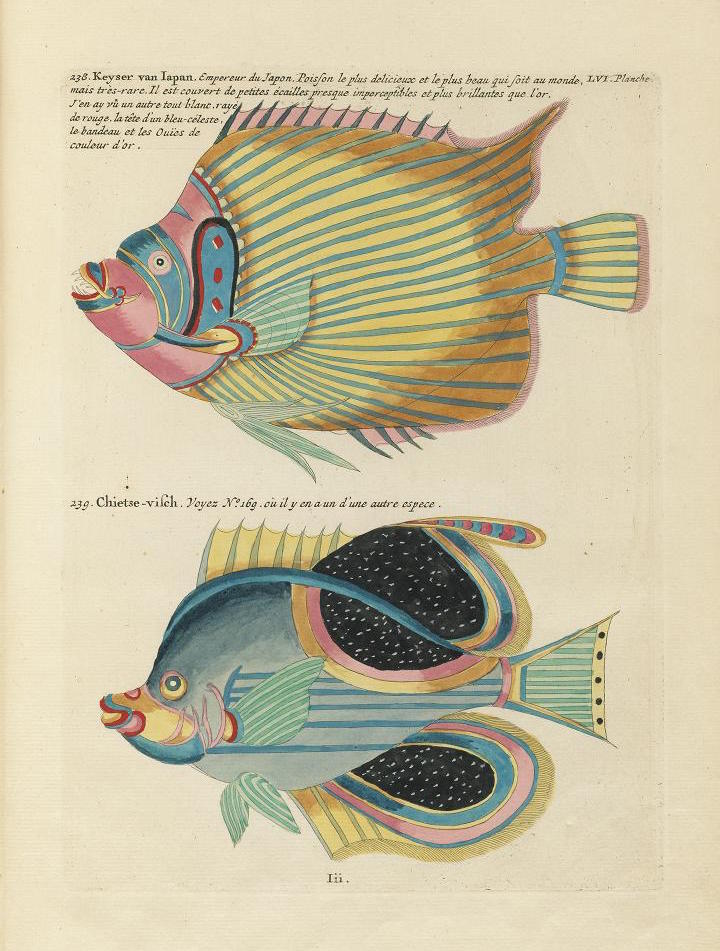

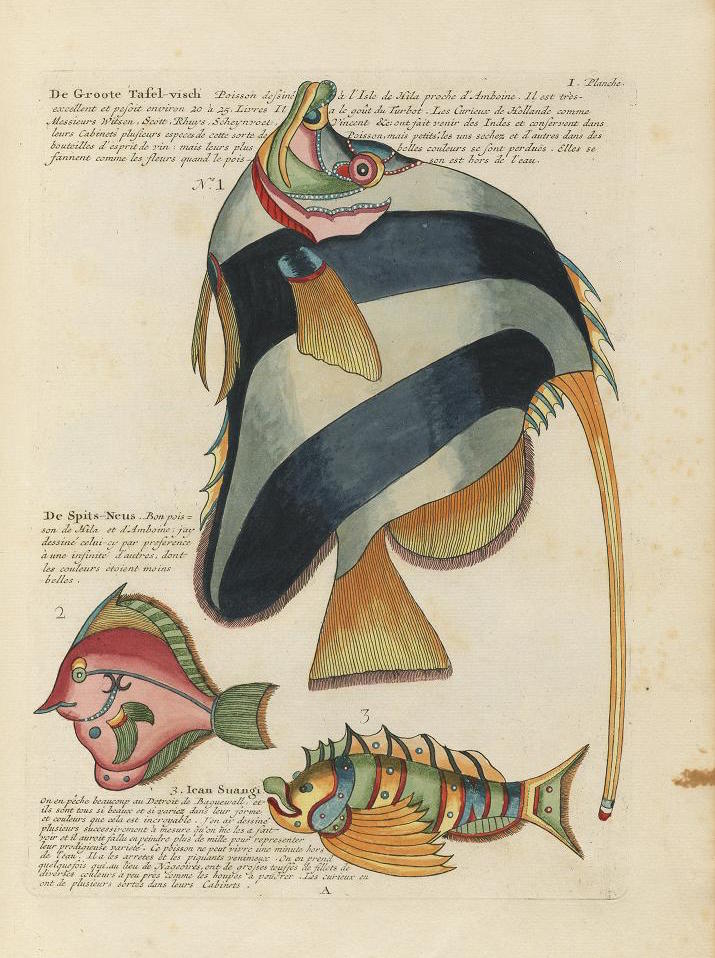

First published in 1719 with a second edition, seen here, in 1754, Renard’s book, whose full title translates to Fishes, Crayfishes, and Crabs, of Diverse Colors and Extraordinary Form, that Are Found Around the Islands of the Moluccas and on the Coasts of the Southern Lands, showed its readers, in full color for the very first time, creatures the likes of which they’d never have had occasion even to imagine. The book’s 460 hand-colored copper engravings depict, according to the Glasgow University Library, “415 fishes, 41 crustaceans, two stick insects, a dugong and a mermaid.”

The specimens in the first part of the book tend toward the realistic, while those of the second “verge on the surreal,” many of which “bear no similarity to any living creatures,” some of which bear “small human faces, suns, moons and stars” on their flanks and carapaces, most possessed of colors “applied in a rather arbitrary fashion,” though brilliantly so. In the short accompanying texts, “several of the fish” — presumably not the mermaid — “are assessed in terms of their edibility and are accompanied by brief recipes.”

Renard himself, who lived from 1678 to 1746, seems to have had a career as colorful as the fish in his book. “As well as spending some seventeen years as a publisher and bookdealer,” he also “sold medicines, brokered English bonds and, more intriguingly, acted as a spy for the British Crown, being employed by Queen Anne, George I and George II.” Far from keeping that part of his life a secret, “Renard used his status as an ‘agent’ to help advertise his books. This particular work is actually dedicated to George I while the title-page describes the publisher as ‘Louis Renard, Agent de Sa Majesté Britannique.’ ”

You can behold more of Poissons, Ecrevisses et Crabes at the Public Domain Review. “If the illustrations are breathtaking to us now, with all the hours of David Attenborough documentaries under our belts,” they write, “one can only imagine the impact this would have had on a European audience of the eighteenth century, to which the exotic ocean life of the East would have been virtually unknown.”

Though received as a respectable scientific work in its day — and even, as the Glasgow University Library puts it, “a product of the Enlightenment” — the book now stands as an enchanting tribute to the combination of a little knowledge and a lot of human imagination.

Related Content:

1,000-Year-Old Illustrated Guide to the Medicinal Use of Plants Now Digitized & Put Online

Wonderfully Weird & Ingenious Medieval Books

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply