Book history buffs don’t need to be told, but the rest of us probably do: incunable—from a Latin word meaning “cradle,” “swaddling clothes,” or “infancy”—refers to a book printed before 1501, during the very first half-century of printing in Europe. An overwhelming number of the works printed during this period were in Latin, the transcontinental language of philosophy, theology, and early science. Yet one of the most revered works of the time, Dante’s Divine Comedy—written in Italian—fully attained its status as a literary classic in the latter half of the 15th century.

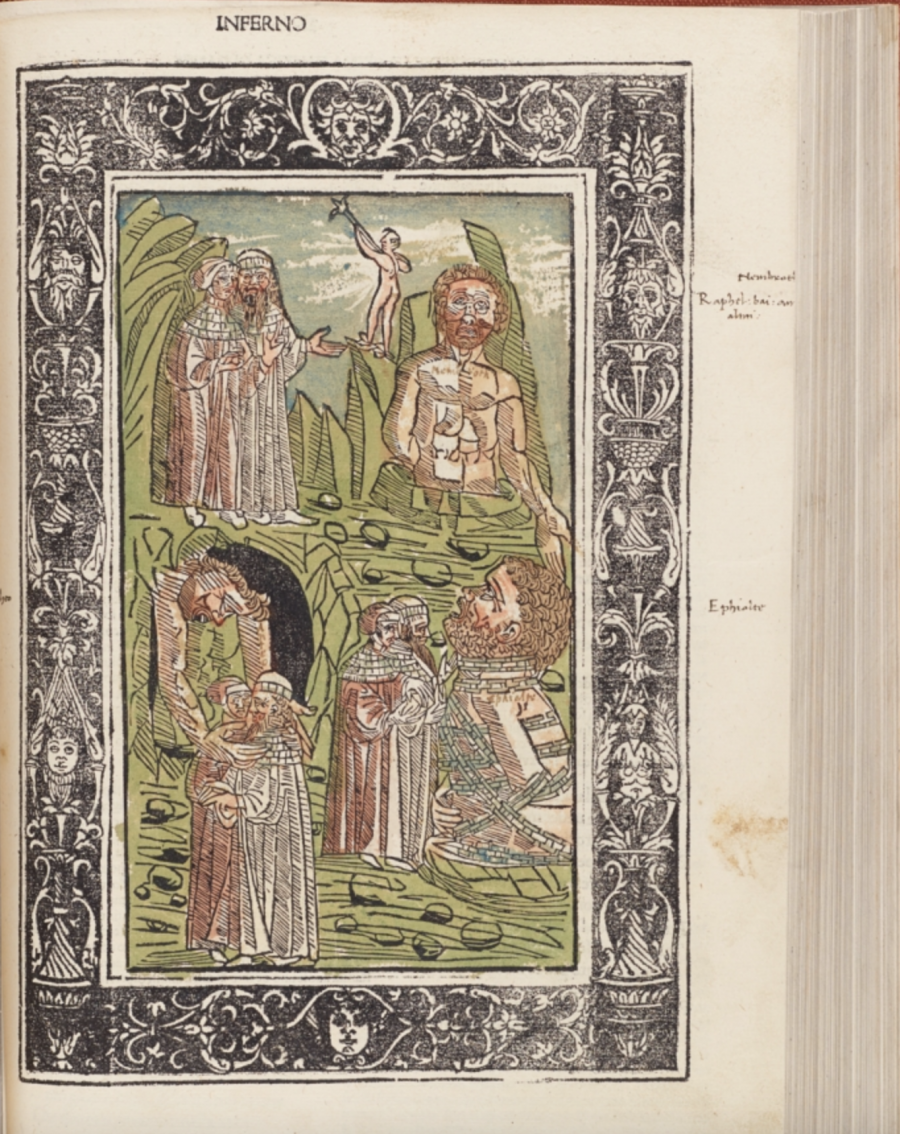

In addition to numerous commentaries and biographies of its author, over 10 editions of the epic Medieval poem— the tale of Dante’s descent into hell and rise through purgatory and paradise—appeared in the period of incunabula, the first in 1472. The 1481 edition contained art based on Sandro Botticelli’s unfinished series of Divine Comedy illustrations. The first fully-illustrated edition appeared in 1491. None of these printings included the word Divine in the title, which did not come into use until 1555. The Commedia, as it was originally called, continued to gain in stature into the 16th century, where it received lavish treatment in other illustrated editions.

You can see Illustrations from three of the editions from the first 100-plus years of printing here, and many more at Digital Dante, a collaborative effort from Columbia University’s Library and Department of Italian. These images, from Columbia’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library, represent a 1497 woodcut edition, at the top, with a number of hand-colored pages; an edition from 1544, above, with almost 90 circular and traditionally-composed scenes, all of them probably hand-colored in the 19th century; and a 1568 edition with three engraved maps, one for each book, like the carefully-rendered visualization of purgatory, below.

Of this last edition, Jane Siegel, Librarian for Rare Books, writes, “the relative lack of illustrations are balanced by the fineness and detail made possible by using expensive copper engravings as a medium, and by the lively decorated and historiated woodcut initials sprinkled throughout the volume at the head of each canto.” Each of these historical artifacts shows us a lineage of craftsmanship in the infancy and early childhood of printing, a time when literary works of art could be turned doubly into masterpieces with illustration and typography that complemented the text. Luckily for lovers of Dante, finely-illustrated editions of the Divine Comedy have never gone away.

You can see more images by entering the Digital Dante collection here.

Related Content:

A Free Course on Dante’s Divine Comedy from Yale University

Botticelli’s 92 Surviving Illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy (1481)

Mœbius Illustrates Dante’s Paradiso

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply