One presumption of television shows like Ancient Aliens and books like Chariots of the Gods is that ancient people—particularly non-western people—couldn’t possibly have constructed the elaborate infrastructure and monumental architecture and statuary they did without the help of extra-terrestrials. The idea is intriguing, giving us the hugely ambitious sci-fi fantasies woven into Ridley Scott’s revived Alien franchise. It is also insulting in its level of disbelief about the capabilities of ancient Egyptians, Mesopotamians, South Americans, South Sea Islanders, etc.

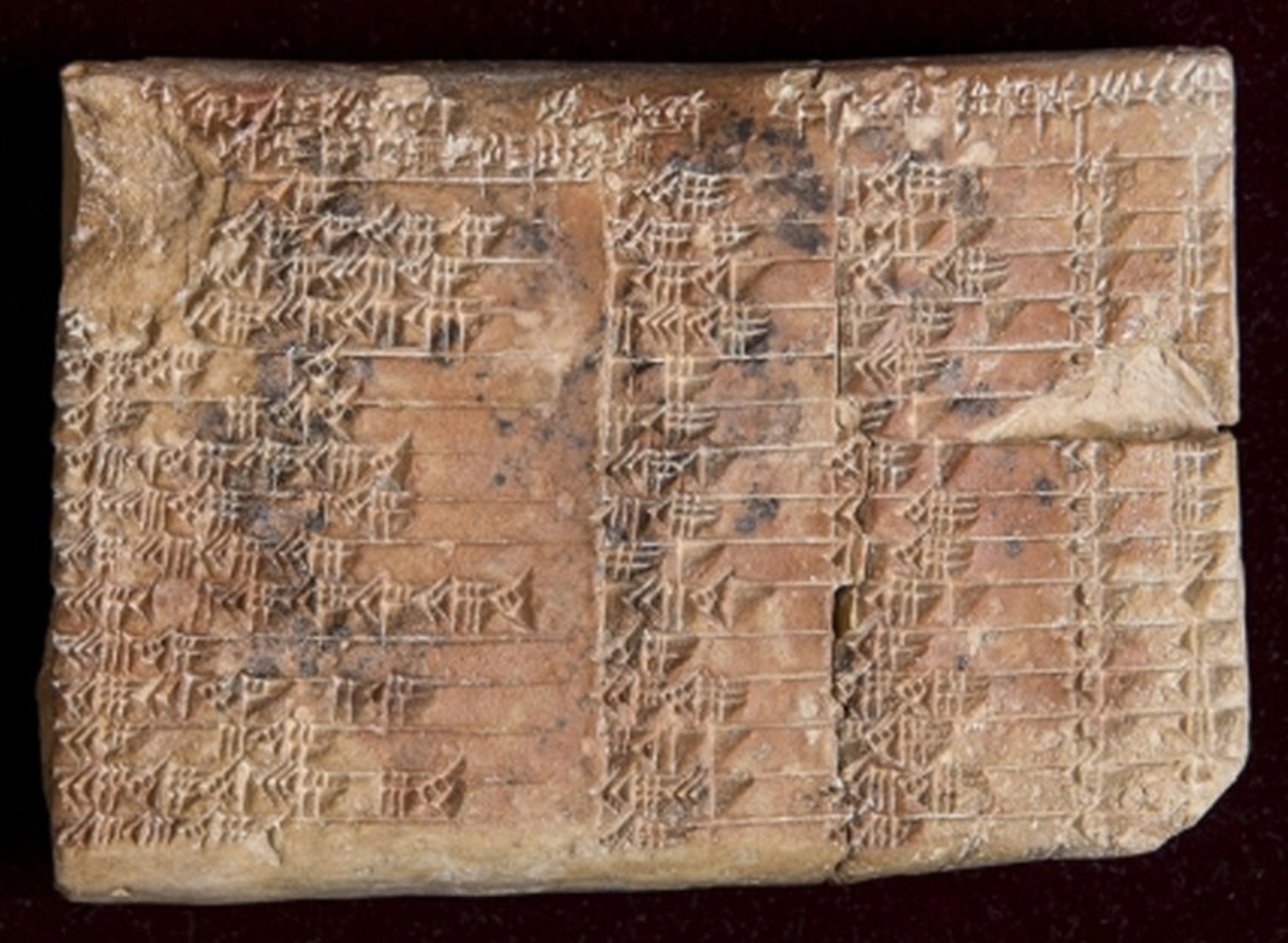

We assume the Greeks perfected geometry, for example, and refer to the Pythagorean theorem, although this principle was probably well-known to ancient Indians. Since at least the 1940s, mathematicians have also known that the “Pythagorean triples”—integer solutions to the theorem—appeared 1000 years before Pythagoras on a Babylonian tablet called Plimpton 322. Dating back to sometime between 1822 and 1762 B.C. and discovered in southern Iraq in the early 1900s, the tablet has recently been re-examined by mathematicians Daniel Mansfield and Norman Wildberger of Australia’s University of New South Wales and found to contain even more ancient mathematical wisdom, “a trigonometric table, which is 3,000 years ahead of its time.”

In a paper published in Historia Mathematica the two conclude that Plimpton 322’s Babylonian creators detailed a “novel kind of trigonometry,” 1000 years before Pythagoras and Greek astronomer Hipparchus, who has typically received credit for trigonometry’s discovery. In the video above, Mansfield introduces the unique properties of this “scientific marvel of the ancient world,” an enigma that has “puzzled mathematicians,” he writes in his article, “for more than 70 years.” Mansfield is confident that his research will fundamentally change the way we understand scientific history. He may be overly optimistic about the cultural forces that shape historical narratives, and he is not without his scholarly critics either.

Eleanor Robson, an expert on Mesopotamia at University College London has not published a formal critique, but she did take to Twitter to register her dissent, writing, “for any historical document, you need to be able to read the language & know the historical context to make sense of it. Maths is no exception.” The trigonometry hypothesis, she writes in a follow-up tweet, is “tediously wrong.” Mansfield and Wildberger may not be experts in ancient Mesopotamian language and culture, it’s true, but Robson is also not a mathematician. “The strongest argument” in the Australian researchers’ favor, writes Kenneth Chang at The New York Times, is that “the table works for trigonomic calculations.” As Mansfield says, “you don’t make a trigonomic table by accident.”

Plimpton 322 uses ratios rather than angles and circles. “But when you arrange it such a way so that you can use any known ratio of a triangle to find the other side of a triangle,” says Mansfield, “then it becomes trigonometry. That’s what we can use this fragment for.” As for what the ancient Babylonians used it for, we can only speculate. Robson and others have proposed that the tablet was a teaching guide. Mansfield believes “Plimpton 322 was a powerful tool that could have been used for surveying fields or making architectural calculations to build palaces, temples or step pyramids.”

Whatever its ancient use, Mansfield thinks the tablet “has great relevance for our modern world… practical applications in surveying, computer graphics and education.” Given the possibilities, Plimpton 322 might serve as “a rare example of the ancient world teaching us something new,” should we choose to learn it. That knowledge probably did not originate in outer space.

Related Content:

How the Ancient Greeks Shaped Modern Mathematics: A Short, Animated Introduction

Hear The Epic of Gilgamesh Read in the Original Akkadian and Enjoy the Sounds of Mesopotamia

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Our society today cannot have a conversation without getting extremely politically correct. This only accomplishes shutting down dialogue and suppressing information.

Him, How is trigonometry extremely politically correct? And what’s wrong with having respect for fellow human beings anyway? It actually enables all people to communicate and work together amicably and roductively which has to be better than the alternative.