Devotees of print may object, but we readers of the 21st century enjoy a great privilege in our ability to store a practically infinite number of digitized books on our computers. What’s more, those computers have themselves shrunk down to such compactness that we can carry them around day and night without discomfort. This would hardly have worked just forty years ago, when books came only in print and a serious computer could still fill a room. The paper book may remain reasonably competitive even today with the convenience refined over hundreds and hundreds of years, but its first handmade generations tended toward lavish, weighty decoration and formats that now look comically oversized.

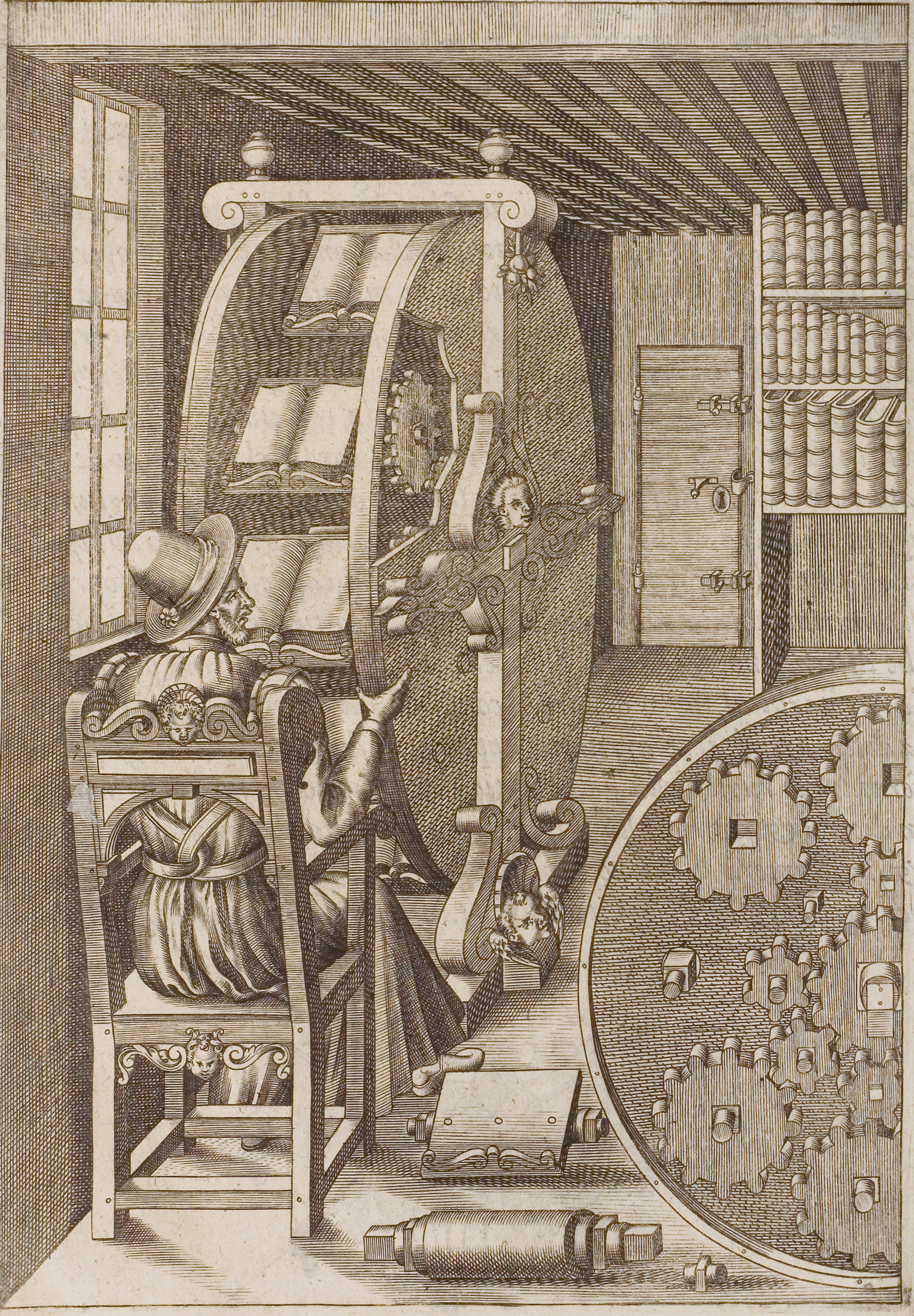

These posed real problems of unwieldiness, one solution to which took the unlikely form of the bookwheel. In 1588’s The Various and Ingenious Machines of Captain Agostino Ramelli, the Italian engineer of that name “outlined his vision for a wheel-o-books that would employ the logic of other types of wheel (water, Ferris, ‘Price is Right’, etc.) to rotate books clockwork-style before a stationary user,” writes the Atlantic’s Megan Garber.

The design used “epicyclic gearing — a system that had at that point been used only in astronomical clocks — to ensure that the shelves bearing the wheel’s books (more than a dozen of them) would remain at the same angle no matter the wheel’s position. The seated reader could then employ either hand or foot controls to move the desired book pretty much into her (or, much more likely, his) lap.” This rotating bookcase gave 16th century readers the ability to read heavy books in place, with far greater ease.

In his 1588 book, Ramelli added:

This is a beautiful and ingenious machine, very useful and convenient for anyone who takes pleasure in study, especially those who are indisposed and tormented by gout. For with this machine a man can see and turn through a large number of books without moving from one spot. Moveover, it has another fine convenience in that it occupies very little space in the place where it is set, as anyone of intelligence can clearly see from the drawing.

Inventors all over Europe created their own versions of the bookwheel during the 17th and 18th centuries, fourteen examples of which still exist. (The one pictured in the middle of the post, built around 1650, now resides in Leiden.) Even architect Daniel Libeskind has built one, based on Ramelli’s design and exhibited in his homeland at the 1986 Venice Biennale. Alas, after it went to Geneva for an exhibition at the Palais Wilson, it fell victim to a terrorist fire bombing. Innovation, it seems, will always have its enemies.

Related Content:

Discover the Jacobean Traveling Library: The 17th Century Precursor to the Kindle

The Art of Making Old-Fashioned, Hand-Printed Books

Wonderfully Weird & Ingenious Medieval Books

Wearable Books: In Medieval Times, They Took Old Manuscripts & Turned Them into Clothes

800 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other Devices

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply