Before J.M. Coetzee became perhaps the most acclaimed novelist alive, he worked as a programer. That may not sound particularly notable these days, but bear in mind that the Nobel laureate and two-time Booker-winning author of Waiting for the Barbarians, Disgrace, and Elizabeth Costello held that day job first at IBM in the early 1960s — back, in other words, when nobody had a computer on their desk. And back when IBM was IBM: that mighty American corporation had brought the kind of computing power it alone could command to branch offices in cities around the world, including London, where Coetzee landed after leaving his native South Africa after graduating from the University of Cape Town.

The years Coetzee spent “writing machine code for computers,” he once wrote in a letter to Paul Auster, saw him “getting so deeply sucked into the process that I sometimes felt I was descending into a madness in which the brain is taken over by mechanical logic.” This must have caused some distress to a literarily minded young man who heard his true calling only from poetry.

“I was very heavily under the influence, in my teens and early twenties, of, first, T.S. Eliot, but then, more substantially, Ezra Pound, and later of German poetry, of Rilke in particular,” he says to Peter Sacks in the interview above, remembering the years before he put poetry aside as a craft in favor of the novel.

“Under the shadowless glare of the neon lighting, he feels his very soul to be under attack,“Coetzee writes, in the autobiographical novel Youth, of the protagonist’s time as a programmer. “The building, a featureless block of concrete and glass, seems to give off a gas, odourless, colourless, that finds its way into his blood and numbs him. IBM, he can swear, is killing him, turning him into a zombie.” Only in the evening can he “leave his desk, wander around, relax. The machine room downstairs, dominated by the huge memory cabinets of the 7090, is more often than not empty; he can run programs on the little 1401 computer, even, surreptitiously, play games on it.”

He could also use these clunky, punchcard-operated computers to write poetry. “In the mid 1960s Coetzee was working on one of the most advanced programming projects in Britain,” writes King’s College London researcher Rebecca Roach. “During the day he helped to design the Atlas 2 supercomputer destined for the United Kingdom’s Atomic Energy Research Establishment at Aldermaston. At night he used this hugely powerful machine of the Cold War to write simple ‘computer poetry,’ that is, he wrote programs for a computer that used an algorithm to select words from a set vocabulary and create repetitive lines.”

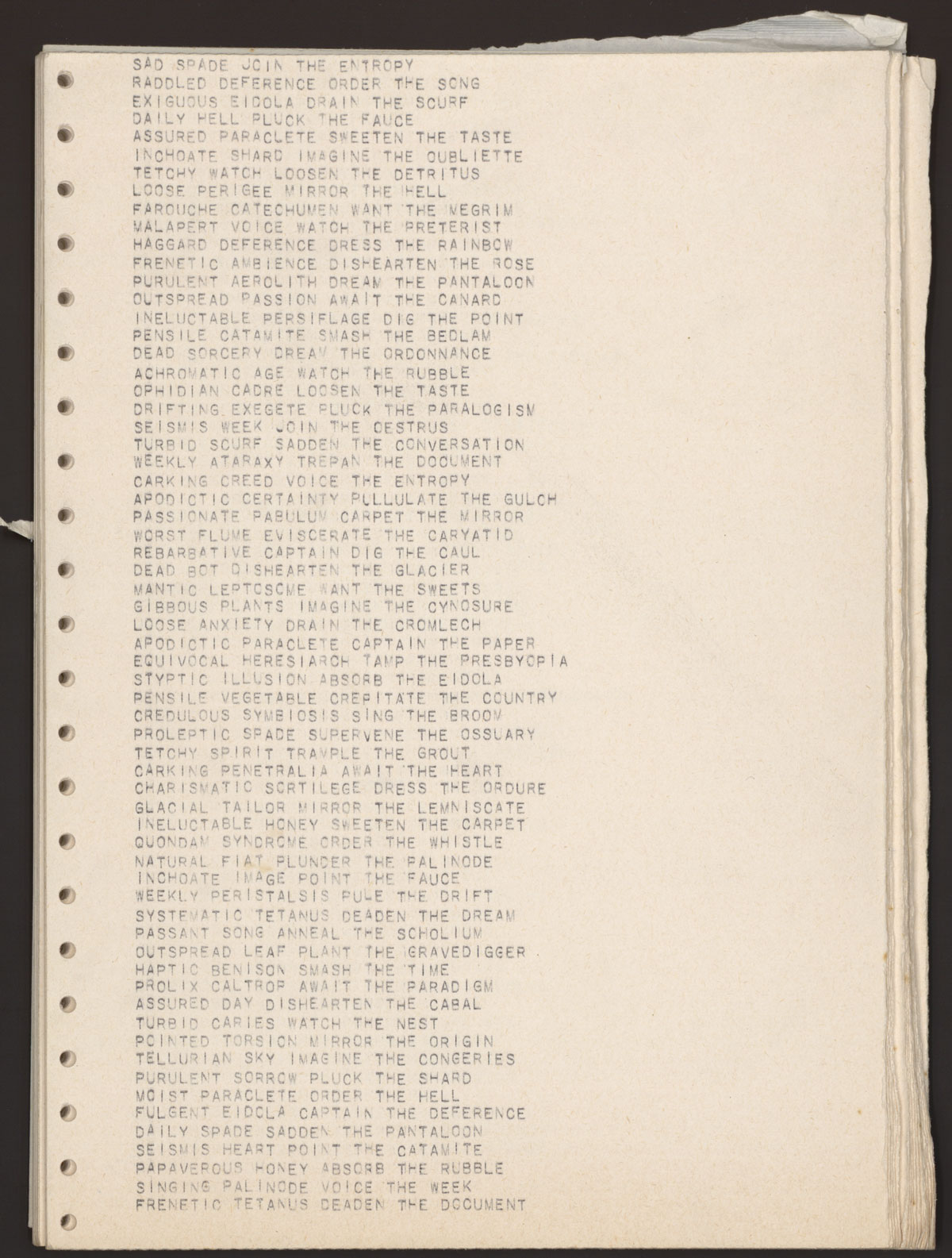

These lines, as seen here in one page of the print-outs held at the Coetzee archive at the University of Texas at Austin’s Harry Ransom Center, include “INCHOATE SHARD IMAGINE THE OUBLIETTE,” “FRENETIC AMBIENCE DISHEARTEN THE ROSE,” “PASSIONATE PABULUM CARPET THE MIRROR,” and “FRENETIC TETANUS DEADEN THE DOCUMENT.” Though he never published these results, writes Roach, he “edited and included phrases from them in poetry that he did publish.” Is this a curious chapter in the early life of a prominent man of letters, or was this realm of “flat metallic surfaces” an ideal forge for the sensibilities of a writer now known, as John Lanchester so aptly put it, for his “unusual quality of passionate coldness” — a kind of brilliant austerity that hardly deadens any of his documents.

Related Content:

J.M. Coetzee on the Pleasures of Writing: Total Engagement, Hard Thought & Productiveness

New Jorge Luis Borges-Inspired Project Will Test Whether Robots Can Appreciate Poetry

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply