In a 1904 letter, Franz Kafka famously wrote, “a book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us,” a line immortalized in pop culture by David Bowie’s “Ashes to Ashes.” Where Bowie referred to the frozen emotions of addiction, the arctic waste inside Kafka may have had much more to do with the agony of writing itself. In the year that he composed his best-known work, The Metamorphosis, Kafka kept a tortured journal in which he confessed to feeling “virtually useless” and suffering “unending torments.” Not only did he need to break the ice, but “you have to dive down,” he wrote on January 30th, “and sink more rapidly than that which sinks in advance of you.”

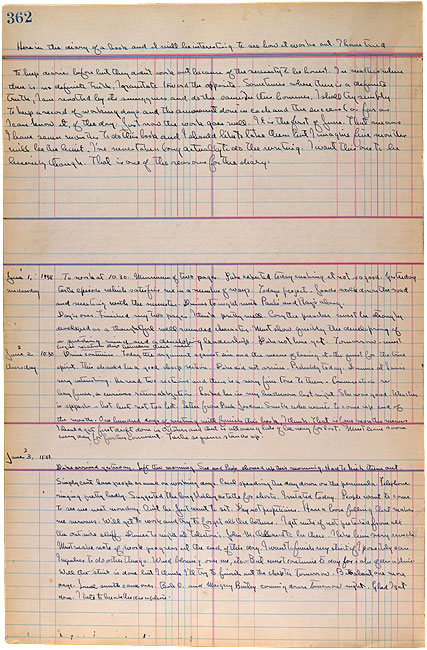

Whether as writers we find the evidence of Kafka’s crippling self-doubt to be a comfort I cannot say. For many people, no matter how successful, or prolific, some degree of pain inevitably attends every act of writing. And many, like Kafka, have left personal accounts of their most productive periods. John Steinbeck struggled mightily during the composition of his masterpiece, The Grapes of Wrath. His journal entries from the period tell the story of a frayed and anxious man overwhelmed by the seeming enormity of his task. But his example is instructive as well: despite his fragile mental state and lack of confidence, he continued to write, telling himself on June 11th, 1938, “this must be a good book. It simply must.” (See some of Steinbeck’s handwritten entries in the image above, courtesy of Austin Kleon.)

In setting the bar so high—“For the first time I am working on a real book,” he wrote—Steinbeck often felt crushed at the end of a day. “My whole nervous system in battered,” he wrote on June 5th. “I hope I’m not headed for a nervous breakdown.” He finds himself a few days later “assailed with my own ignorance and inability.” He continues in this vein. “Where has my discipline gone?” he asks in August, “Have I lost control?” By September he’s seeking perspective: “If only I wouldn’t take this book so seriously. It is just a book after all, and a book is very dead in a very short time. And I’ll be dead in a very short time too. So to hell with it.” The weight of expectation comes and goes, but he keeps writing.

The “private fruit” of Steinbeck’s diary entries, writes Maria Popova, “is in many ways at least as important and morally instructive” as the novel itself. At least that may be so for writers who are also beset by devastating neuroses. For Steinbeck, the diary (published here) was “a tool of discipline” and “hedge against self-doubt.” This may sound counterintuitive, but keeping a diary, even when the novel stalls, is itself a discipline, and an acknowledgement of the importance of being honest with oneself, allowing turbulence and doldrums to be a conscious part of the experience.

Steinbeck “feels his feelings of doubt fully, lets them run through him,” writes Popova, “and yet maintains a higher awareness that they are just that: feelings, not Truth.” His confrontations with negative capability can sound like “Buddhist scripture,” anticipating Ray Bradbury’s Zen in the Art of Writing. We needn’t attribute any religious significance to Steinbeck’s journals, but they do begin to sound like confessions of the kind many mystics have recorded over the centuries, including the imposter syndrome many a saint and bodhisattva has admitted to feeling. “I’m not a writer,” he laments in one entry. “I’ve been fooling myself and other people.” Nonetheless, no matter how excruciating, lonely, and confusing the effort, he resolved to develop a “quality of fierceness until the habit pattern of a certain number of words is established.” A ritual act, of a sort, which “must be a much stronger force than either willpower or inspiration.”

In the audio above, hear actor Paul Hecht read excerpts from Steinbeck’s diaries in an episode of the Morgan Library’s Diary Podcast. You can read Steinbeck’s diaries in the published volume, Working Days: The Journal of The Grapes of Wrath, 1938–1941.

via Austin Kleon

Related Content:

John Steinbeck’s Six Tips for the Aspiring Writer and His Nobel Prize Speech

See John Steinbeck Deliver His Apocalyptic Nobel Prize Speech (1962)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply