At both a geographical and historical distance, the Soviet Union doesn’t look like much of a place for kids. If you grew up during the Cold War in, say, the United States, you might well have the impression (of which The Simpsons’ “Worker and Parasite” remains the defining crystallization) of a gray, harshly utilitarian land behind the Iron Curtain concerned with nothing more whimsical than bread lines and production quotas. But if you grew up in the Soviet Union, at least at one of the right times and in one of the right places, you might feel a now much-discussed nostalgia, not for the economic difficulties of your Soviet childhood, but for the sensibilities of the vanished society you grew up in. An online interactive database called Playing Soviet: The Visual Languages of Early Soviet Children’s Books, 1917–1953 provides a kid’s-eye view into the early decades of that society.

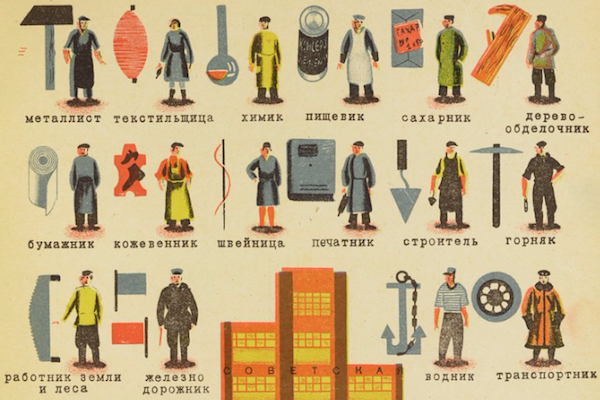

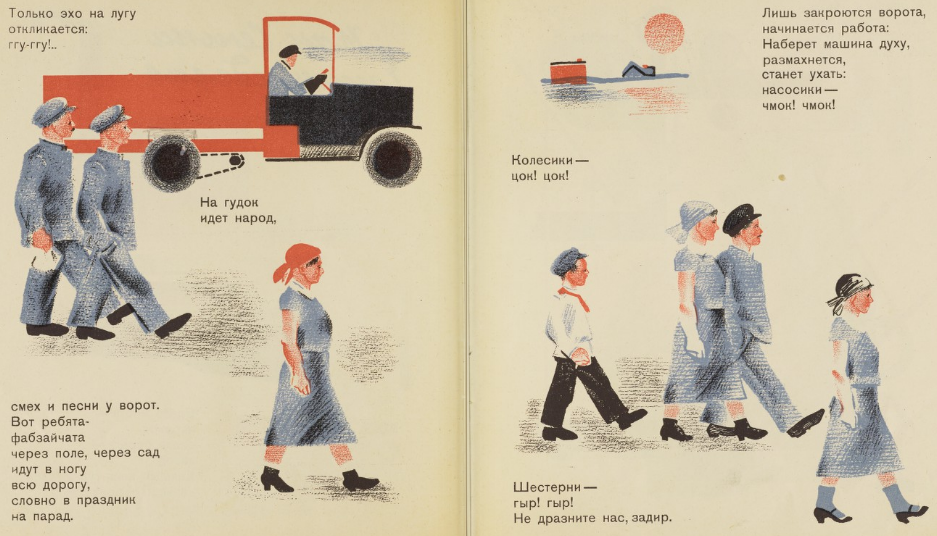

A project of the Cotsen Collection at Princeton’s Firestone Library, the archive contains a variety of fully digitized children’s books that show one venue in which, amid these years of “Russia’s accelerated violent political, social and cultural evolution,” in the words of the database’s front page, certain kinds of graphic art could flourish. “The illustration and look of Soviet children’s books was of tantamount importance as a vehicle for practical and concrete information in the new Soviet regime.”

This ambitious effort, driven by “directives for a new kind of children’s literature” to be “founded on the assumption that the ‘language of images’ was immediately comprehensible to the mass reader, far more so than the typed word,” brought in a great many artists and designers such as Alexander Deineka, El Lissitzky, and Vladimir Lebedev, tasking them all with creating “imaginative models for Soviet youth in the new languages of Soviet modernism.”

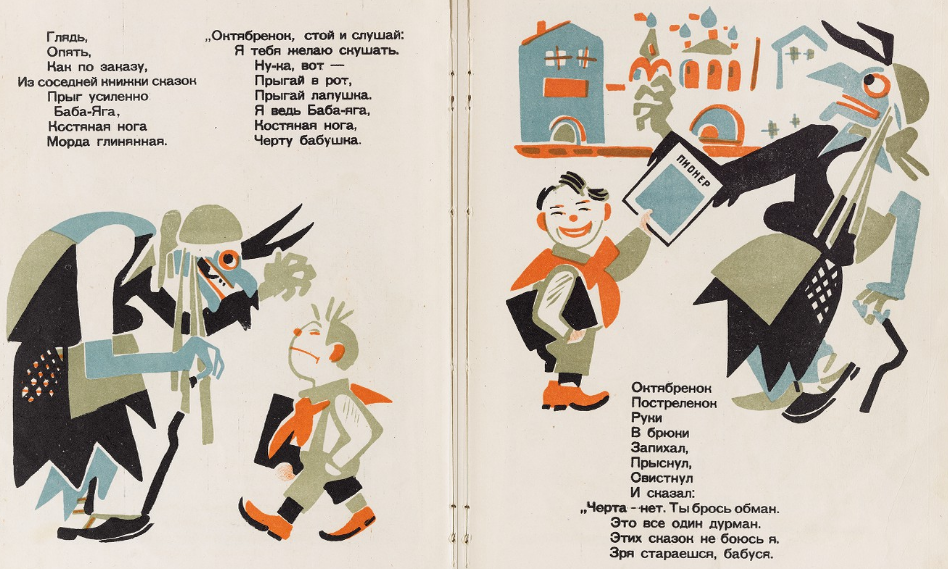

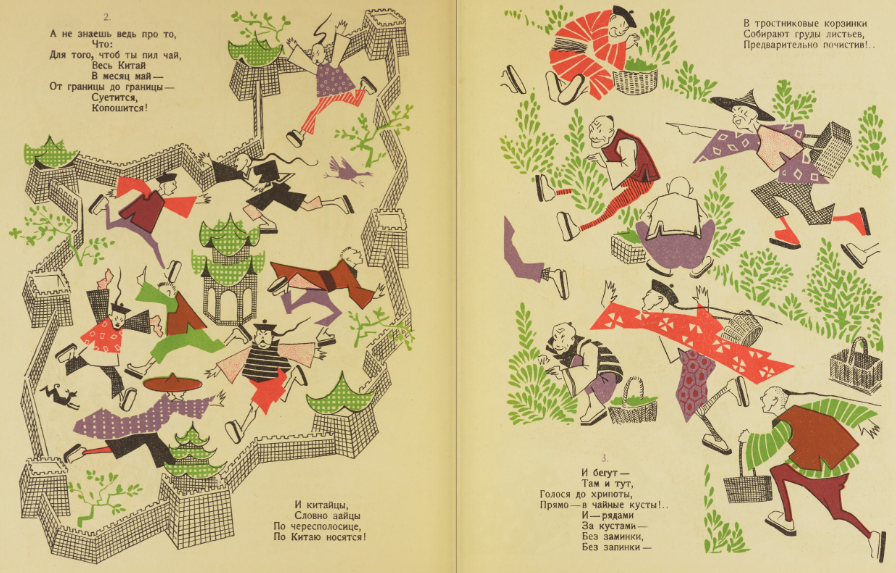

Mental Floss’ Shaunacy Ferro notes how many of the books “were designed to indoctrinate children into the world of the ‘right’ way to think about Soviet culture and history,” pointing to a volume called How the Revolution Was Victorious, which meant “to ensure the correct interpretation of the anti-governmental coup among the young generation of new Soviet readership.” Some of the other reading material that resulted, like 1930’s industrially focused What Are We Building? or the slightly earlier How Senka Ezhik Made a Knife, wears its instructional value on its sleeve (or rather, its cover). Others, like 1925’s The Little Octobrist Rascal or that same year’s China-set A Cup of Tea, offer higher doses of playfulness mixed in with the ideology.

Playing Soviet also includes the work of Vladimir Mayakovsky, whose Whom Should I Be?, a representative book from the “golden age” of Soviet Children’s literature, we featured here on Open Culture earlier this year. Russia Beyond the Headlines’ Alexandra Gueza highlights Mayakovsky’s What is Good and What is Bad? (“in which he explains that walking in the rain and thunderstorms is bad, cleaning your teeth is good, fighting with the boys is bad, while studying is good”) and October 1917–1918: Heroes and Victims of the Revolution, whose “good guys” include “a worker, a Red Army soldier, a sailor, a seamstress” and whose “bad guys” include “a factory owner, a landowner, a rich farmer, a priest, a merchant.” Goodnight Moon it certainly isn’t, but then, how many American children’s books had to attempt a fundamental reinvention of society?

via Hyperallergic

Related Content:

Soviet-Era Illustrations Of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit (1976)

Enter an Archive of 6,000 Historical Children’s Books, All Digitized and Free to Read Online

Hayao Miyazaki Picks His 50 Favorite Children’s Books

The First Children’s Picture Book, 1658’s Orbis Sensualium Pictus

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Большое спасибо. For returning our childhood days. No thanks is sufficient to express my gratitude. Thank you once again.

Nostalgia? For GULAGs? For genocide?

Some of us had a Very Nice childhood during the so called Sovjet Time.

Good and tasty food, even at shool.

We spent summer with parents in Krim or Sochi twice a year and could stay at the pioneer camp during 3 summer mothes.

We could extend our talents for free at different sport clubs, sing and dance, swim and paint for free in different professional clubs.

We could join Special language or musical schools with the best teachers who had really good and qualified education.

These were not private schools.

The understanding of word „ Gulag„ and all these wrong things came later, when we were ready enough to analize and understand what was really going on.

Every time and every country has its own „propaganda.„

But I am sure, that many of us, born after 1953 had a lot of fun during our childhood and we were reading a lot of wonderful books, which were written by famous writers, both in Russia and all over abroad.

That was a good time of the „ культ„ оf the Book.

I see You have grown up reading Your propaganda children books too