“These go up to eleven,” Spinal Tap famously said of the amplifiers that, so they claimed, took them to a higher level in rock music. But the work of Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg, one of the best-known figures in the history of avant-garde music, went up to twelve — twelve tones, that is. His “twelve-tone technique,” invented in the early 1920s and for the next few decades used mostly by he and his colleagues in the Second Viennese School such as Alban Berg, Anton Webern, and Hanns Eisler, allowed composers to break free of the traditional Western system of keys that limited the notes available for use in a piece, instead granting each note the same weight and making none of them central.

This doesn’t mean that composers using Schoenberg’s twelve-tone technique could just use notes at random in complete atonality, but that a new set of considerations would organize them. “He believed that a single tonality could include all twelve notes of the chromatic scale,” writes Bradford Bailey at The Hum, “as long as they were properly organized to be subordinate to tonic (the tonic is the pitch upon which all others are referenced, in other words the root or axis around which a piece is built).” The mathematical rigor underlying it all required some explanation, and often mathematical and musical concepts — mathematics and music being in any case intimately connected — become much clearer when rendered visually.

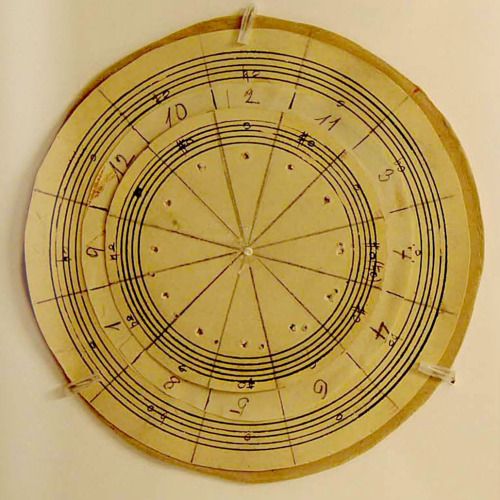

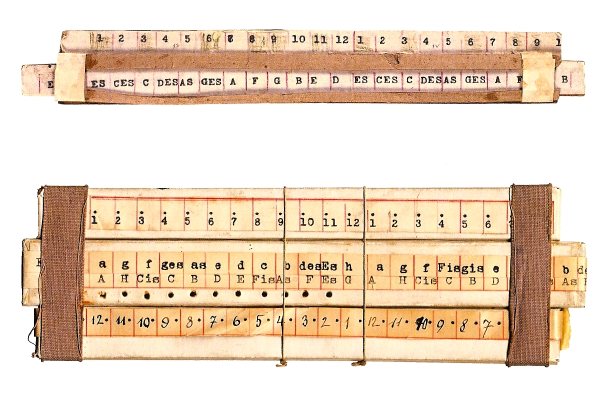

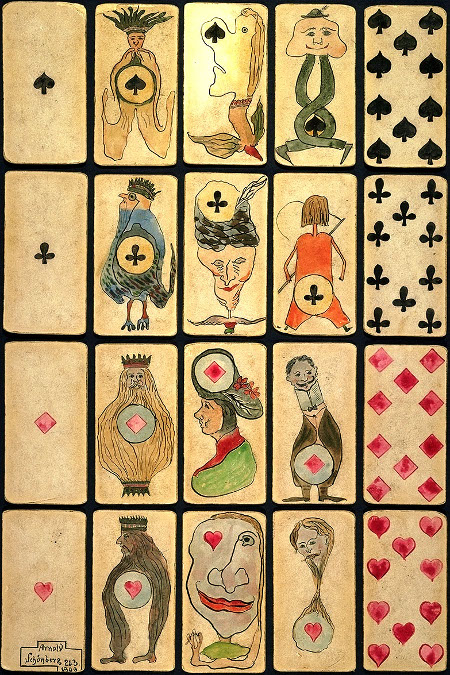

Hence Schoenberg’s twelve-tone wheel chart pictured at the top of the post, one of what Arnold Schoenberg’s Journey author Allen Shawn describes as “no fewer than twenty-two different kinds of contraptions” — including “charts, cylinders, booklets, slide rules” — “for transposing and deriving twelve-tone rows” needed to compose twelve-tone music. (See the slide ruler above too.) “The distinction between ‘play’ and ‘work’ is already hard to draw in the case of artists,” writes Shawn, “but in Schoenberg’s case it is especially hard to make since he brought discipline, originality, and playfulness to many of his activities.” These also included making special playing cards (two of whose sets you can see here and here) and even his own version of chess.

As Shawn describes it, Koalitionsscach, or “Coalition Chess,” involves “the armies of four countries arrayed on the four sides of the board, for which he designed and constructed the pieces himself.” Instead of an eight-by-eight board, Coalition Chess uses a ten-by-ten, and the pieces on it “represent machine guns, artillery, airplanes, submarines, tanks, and other instruments of war.” The rules, which “require that the four players form alliances at the outset,” add at least a dimension to the age-old standard game of chess — a form that, like traditional Western music, humanity will still be struggling to master decades and even centuries hence. But apparently, for a mind like Schoenberg’s, chess and music as he knew them weren’t nearly challenging enough.

Related Content:

Vi Hart Uses Her Video Magic to Demystify Stravinsky and Schoenberg’s 12-Tone Compositions

Interviews with Schoenberg and Bartók

John Coltrane Draws a Picture Illustrating the Mathematics of Music

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply