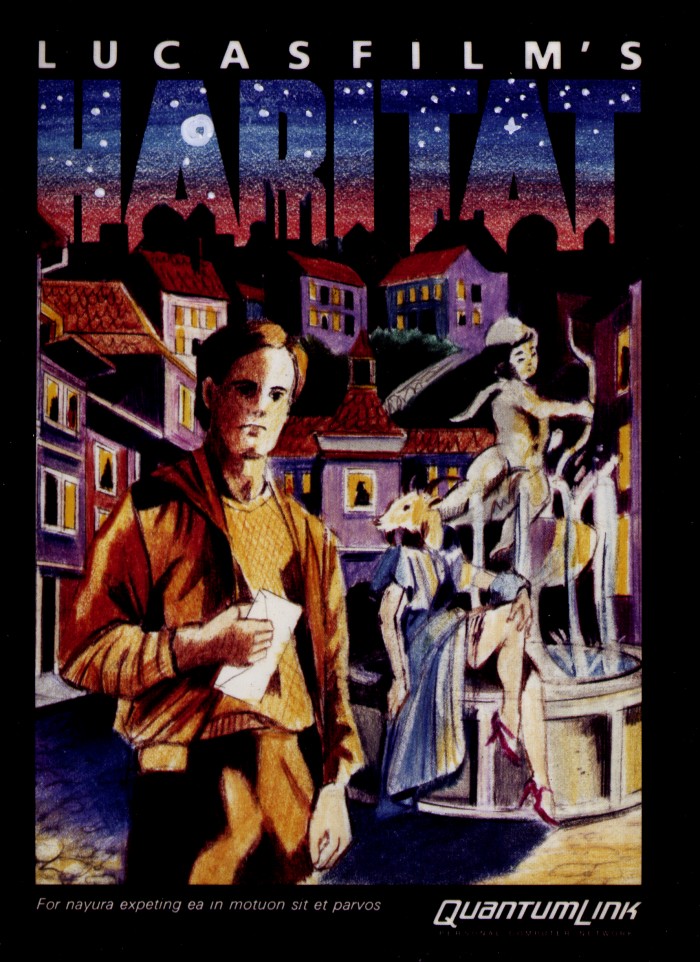

Long before World of Warcraft, before Everquest and Second Life, and even before Ultima Online, computer-gamers of the 1980s looking for an online world to explore with others of their kind could fire up their Commodore 64s, switch on their dial-up modems, and log into Habitat. Brought out for the Commodore online service Quantum Link by Lucasfilm Games (later known as the developer of such classic point-and-click adventure games as Maniac Mansion and The Secret of Monkey Island, now known as Lucasarts), Habitat debuted as the very first large-scale graphical virtual community, blazing a trail for all the massively multiplayer online role-playing games (or MMORPGs) so many of us spend so much of our time playing today.

Designed, in the words of creators Chip Morningstar and F. Randall Farmer, to “support a population of thousands of users in a single shared cyberspace,” Habitat presented “a real-time animated view into an online simulated world in which users can communicate, play games, go on adventures, fall in love, get married, get divorced, start businesses, found religions, wage wars, protest against them, and experiment with self-government.” All that happened and more within the service’s virtual reality during its pilot run from 1986 to 1988. The features both cautiously and recklessly implemented by Habitat’s developers, and the feedback they received from its users, laid down the template for all the more advanced graphical online worlds to come.

At the top of the post, you can watch Lucasfilm’s original Habitat promotional video promise a “strange new world where names can change as quickly as events, surprises lurk at every turn, and the keynotes of existence are fantasy and fun,” one where “thousands of avatars, each controlled by a different human, can converge to shape an imaginary society.” (All performed, the narrator notes, “with the cooperation of a huge mainframe computer in Virginia.”) The form this society eventually took impressed Habitat’s creators as much as anyone, as Farmer writes in his “Habitat Anecdotes” from 1988, an examination of the most memorable happenings and phenomena among its users.

Farmer found he could group those users into five now-familiar categories: the Passives (who “want to ‘be entertained’ with no effort, like watching TV”), the Active (whose “biggest problem is overspending”), the Motivators (the most valuable users, for they “understand that Habitat is what they make of it”), the Caretakers (employees who “help the new users, control personal conflicts, record bugs” and so on), and the Geek Gods (the virtual world’s all-powerful administrators). Sometimes everyone got along smoothly, and sometimes — inevitably, given that everyone had to define the properties of this brand new medium even as they experienced it — they didn’t.

“At first, during early testing, we found out that people were taking stuff out of others’ hands and shooting people in their own homes,” Farmer writes. Later, a Greek Orthodox Minister opened Habitat’s first church, but “I had to eventually put a lock on the Church’s front door because every time he decorated (with flowers), someone would steal and pawn them while he was not logged in!” This citizen-governed virtual society eventually elected a sheriff from among its users, though the designers could never quite decide what powers to grant him. Other surprisingly “real world” institutions developed, including a newspaper whose user-publisher “tirelessly spent 20–40 hours a week composing a 20, 30, 40 or even 50 page tabloid containing the latest news, events, rumors, and even fictional articles.”

Though developing this then-advanced software for “the ludicrous Commodore 64” posed a serious technical challenge, write Farmer and Morningstar in their 1990 paper “The Lessons of Lucasfilm’s Habitat,” the real work began when the users logged on. All the avatars needed houses, “organized into towns and cities with associated traffic arteries and shopping and recreational areas” with “wilderness areas between the towns so that everyone would not be jammed together into the same place.” Most of all, they needed interesting places to visit, “and since they can’t all be in the same place at the same time, they needed a lot of interesting places to visit. [ … ] Each of those houses, towns, roads, shops, forests, theaters, arenas, and other places is a distinct entity that someone needs to design and create. Attempting to play the role of omniscient central planners, we were swamped.”

All this, the creators discovered, required them to stop thinking like the engineers and game designers they were, giving up all hope of rigorous central planning and world-building in favor of figuring out the tricker problem of how, “like the cruise director on an ocean voyage,” to make Habitat fun for everyone. Farmer faces that question again today, having launched the open-source NeoHabitat project earlier this year with the aim of reviving the Habitat world for the 21st century. As much progress as graphical multiplayer online games have made in the past thirty years, the conclusion Farmer and Morningstar reached after their experience creating the first one holds as true as ever: “Cyberspace may indeed change humanity, but only if it begins with humanity as it really is.”

Related Content:

Free: Play 2,400 Vintage Computer Games in Your Web Browser

Long Live Glitch! The Art & Code from the Game Now Released into the Public Domain

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

very nice thanks

Good experience and helpful infogrowing provided in the article. keep prociding and grow your network