In one of the most impassioned and beautifully written defenses of Burkean conservatism I have ever read, the poet Wendell Berry took government projects of both the left and right to task, proclaiming in 1968 that the emergence of a massive bureaucracy was a tragic sign of the “loss of the future.” His argument is similar to one made over twenty years earlier by the Trotskyist-turned-conservative writer James Burnham, whose 1941 book The Managerial Revolution predicted “at each point,” wrote George Orwell in a thorough review, “a continuation of the thing that is happening.” A “managerial” central state, Burnham also argued, inevitably brought about a “loss of the future.”

Neither the contemplative Berry nor the incisive Burnham have been able to account for one historically inescapable fact: the periods in which 20th century societies imagined the future most vividly were those most dominated by bureaucratic, technocratic, centralized political economies. This is true under conservative governments like that of the U.S. under Eisenhower, in which huge infrastructure projects—from the highway system to hydroelectric dams— rearranged the lives of millions.

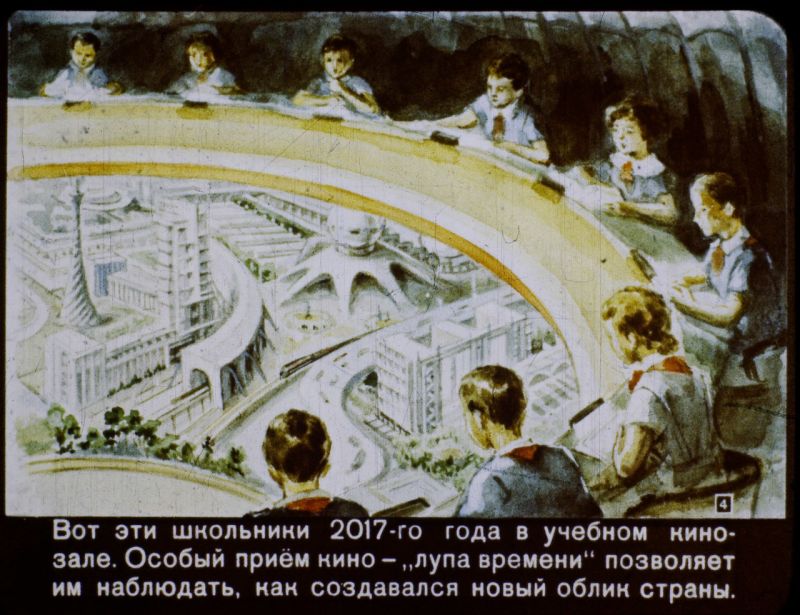

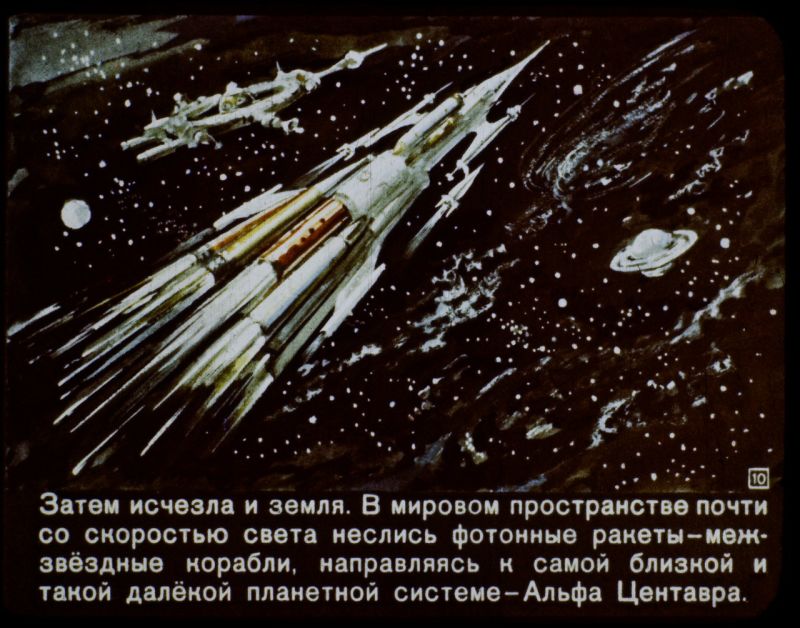

And it was true under Khrushchev’s Soviet state, whose Virgin Lands campaign did the same. Indeed, mid-century Soviet “expectations were pretty similar to the futuristic predictions of Americans,” writes Matt Novak, “with a touch more Communism, of course.” Unsurprising, perhaps, given that the two nations were locked in competition over the domination of both earth and space.

Novak’s understatement is fully warranted. Although the people in images like those you see here tend to appear in more collective arrangements, their sci-fi surroundings almost mirror those in the images from the U.S. that were parodied by The Jetsons two years after this 1960 collection. These detailed scenarios come from a “retro-futuristic filmstrip, which would have been played through a Diafilm,” a kind of slide projector. It’s a vision, it just so happens, of our time, 2017, but it looks backward to get there, both in its technology and its design. The illustration above, for example, “was almost certainly inspired by the Futurama exhibit from the 1939 New York World’s Fair.” (Itself built, we may note, on the shoulders of Roosevelt’s New Deal.)

You can see many more of these illustrations at Paleofuture, and at the top of the post watch a video version with “jazzy music and star wipes.” You may find these visions quaint, charming in their naiveté and inaccuracy—yet often quaintly prescient as well. Retro-futurism’s appeal to us seems to rest principally in how silly it can seem in hindsight, even when it gets things right. Perhaps it is the case that the most fully-realized, totalizing visions of tomorrow are as far-fetched as the controlling societies that produce them are unsustainable. As Bob Duggan writes at Big Think, for example, we are bound to associate the “undead art movement” of Italian Futurism with the very short-lived regime of Italian Fascism. Maybe the degree to which a government lacks a future is in inverse proportion to the intensity of its retro-futurism.

So what exactly is the relationship between state power and utopian futurism? The question invites a dissertation, and surely many have been written, as they have on the symptomology of the techno-dystopian and urban apocalyptic forms of futurism. We might begin by wondering what our actual 2017 will look like 57 years from now. What will people in 2074 make of our endless culture of revivalism, from zombie steampunk to retreads and remakes of everything from Ghost in the Shell, to The Matrix, to Star Wars? Who can say. Perhaps, for whatever sociological reason, we are suffering, as Berry put it, from a loss of the future.

via Paleofuture

Related Content:

Soviet Artists Envision a Communist Utopia in Outer Space

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply