Like digging for fossils or panning for gold, the research process can be a tedious affair. But for any researcher, long days of searching and reading will eventually result in discovery. These are the moments scholars cherish. It’s the chance discovery, however rare, that makes the long hours and bleary late nights worthwhile. And some finds can change an entire field. Such was the discovery of St. John’s College PhD student Giovanni Varelli, who, in 2014, found what is now believed to be, writes Cambridge University, “the earliest known practical example of polyphonic music,” that is, music consisting of two or more melodic lines working together simultaneously.

You can hear the short composition—written in praise of the patron saint of Germany, Saint Boniface—performed above by St. John’s undergraduates Quintin Beer and John Clapham. Prior to Varelli’s discovery of this piece of music, the earliest polyphonic music was thought to date to the year 1000, from a collection called The Winchester Troper. Varelli’s discovery may date to 100 years earlier, around the year 900, and was found at the end of a manuscript of the Life of Bishop Maternianus of Reims. One reason musicologists had so far overlooked the piece, Varelli says, is that “we are not seeing what we expected.”

Typically, polyphonic music is seen as having developed from a set of fixed rules and almost mechanical practice. This changes how we understand that development precisely because whoever wrote it was breaking those rules. It shows that music at this time was in a state of flux and development.

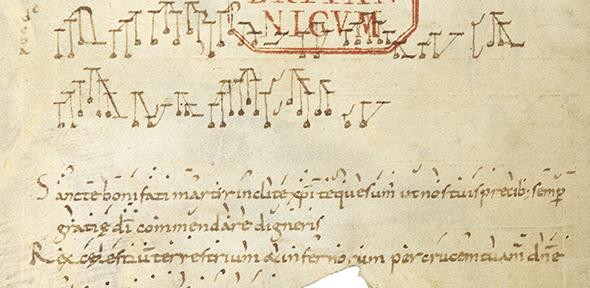

Varelli’s specialization in early music notation also provided him with the training needed to recognize the piece, which was written using “an early form of notation that predates the invention of the stave” (see the piece below). According to British Library curator Nicolas Bell, “when this manuscript was first catalogued in the eighteenth century, nobody was able to understand these unusual symbols.” Varelli’s discovery shows a deviation from “the convention laid out in treatises at the time” and points toward the development of a musical technique that “defined most European music up until the 20th century.”

Varelli gives us a sense of how important this discovery is to scholars of early music: “the rules being applied here laid the foundations for those that developed and governed the majority of western music history for the next thousand years. This discovery shows how they were evolving, and how they existed in a constant state of transformation, around the year 900.”

So there you have it. If you’re stuck in the doldrums of a research project, waiting for the wind to pick up, don’t despair. The next rare artifact, treatise, or manuscript may be waiting for someone with exactly your specialized insights to decipher its secrets.

Related Content:

Hear a 9,000 Year Old Flute—the World’s Oldest Playable Instrument—Get Played Again

Listen to the Oldest Song in the World: A Sumerian Hymn Written 3,400 Years Ago

Hear the World’s Oldest Instrument, the “Neanderthal Flute,” Dating Back Over 43,000 Years

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

So Beautiful.….

As true as this form is to original music, it by far not the earliest form of multi-voiced composition. Most original people, those who existed before anyone knew, performed musical dialogue that had more than a single performer and harmonized these exchanges.

Yes, I think you’re absolutely right, Grady. This is the earliest transcribed example in European music. A huge find for musicologists, but not by any means the original appearance of polyphony in human culture.

In what language is this written?

Thank you.

Dear all,

in my lightweight view this may be a piece of heterophonic, not polyphonic music. What do you think?

Thanks a lot nevertheless

Yours Amicus

How is the tempo determined? It is, to the modern ear, frightfully slow.

The notation has no information about the rhythm, note-length, speed or style of the music. Nor are the actual notes indicated — only where the tune goes either up, or down, and by a fairly approximately level. This is fascinating to know about — but the transcription, and performance, remains 95% subjective guesswork.

This would not qualify as what we call “polyphony”.

What they are singing has been done all over the world ever since humans began to sing. The voices are spaced by natural consonances which occur without much reflection by singers with different ranges- men, women, children, and of course singing in actual unison, which several sections in this piece are as well. But even singing in 5ths and 4ths does not constitute polyphony either, that too has been done all over the world. They two gentlemen are singing the same basic melodic contour in natural harmony- not two distinct melodies.

Sorry- hardly Earth-shattering, and pretty boring to boot.