Given the image of Communist Russia we’ve mostly inherited from Cold War Hollywood propaganda and cherry-picked TV documentaries, we tend to think of Communist art as sterile, brutalist, devoid of expressive emotion and experiment. But this has never been entirely so. While Party-approved social realism dominated in certain decades, experimental Russian animation, film, design, and literature flourished, even under extremely harsh conditions one wouldn’t wish on any artist.

In the early days of the Revolution, one of the most influential forms of expression, Russian Futurism, brought its avant-gardism to the masses, and praised the Revolution while formally challenging every received idea or doctrine. Beginning in the early 20th century and working until the Soviet Union was formed and Trotsky banished, Futurist poets and artists like Vladimir Mayakovsky, Kazimir Malevich, Nalia Goncharova, and Velimir Khlebnikov contributed to a style called “Zaum,” a word, as we noted in a previous post, that can mean “transreason” or “beyond sense.” (A very unscientific, bourgeois approach, it would later be alleged by the Central Committee.)

Like modernist movements all over Europe, Russian Futurism took risks in every medium, but took a much more Dadaist approach than the Italian Futurists who had partly inspired them. They published prolifically—creating hundreds of books and journals between 1910 and 1930. A new book from Getty Research Institute curator Nancy Perloff, Explodity: Sound, Image, and Word in Russian Futurist Book Art, covers the first five years of that period—pre-Revolutionary but no more nor less radical. Her book is accompanied by an “interactive companion,” a site that allows users to see the publications and poems Perloff examines. If you scroll down to the bottom of the page, you’ll find a link to “digitized Russian avant-garde books from the Getty Research Institute.”

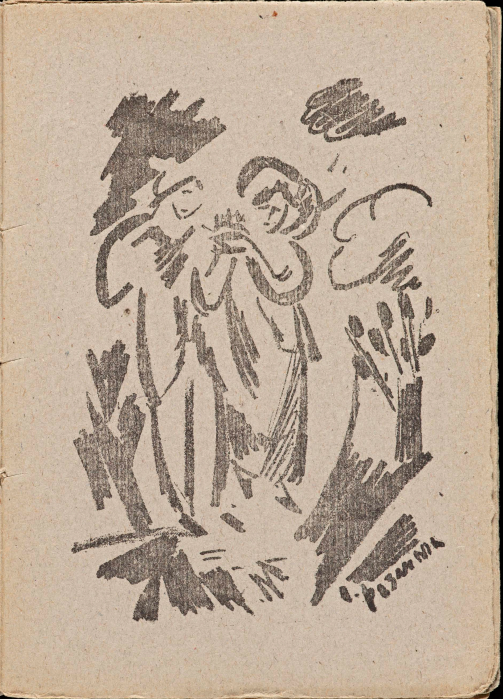

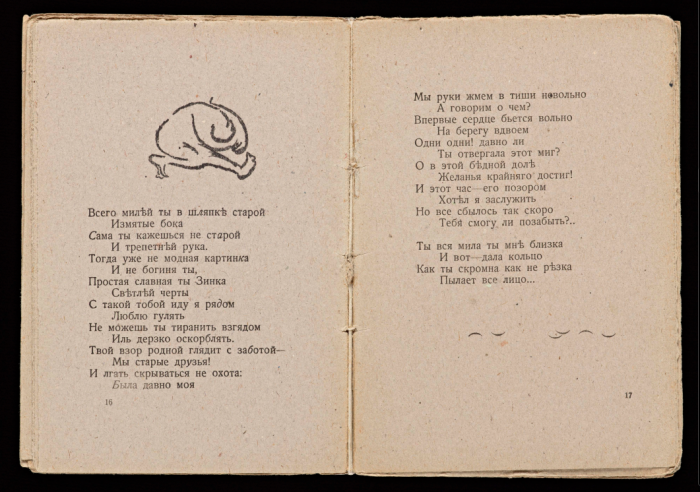

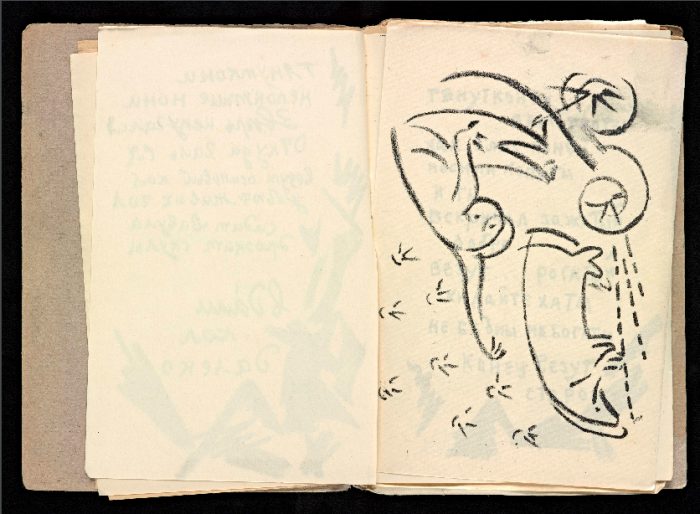

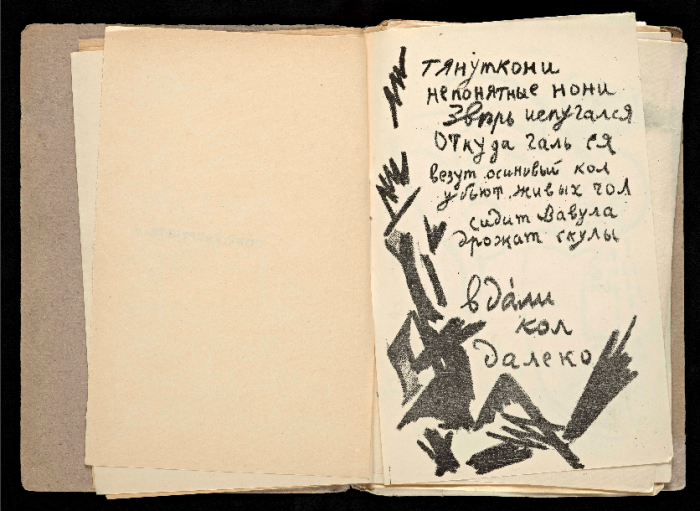

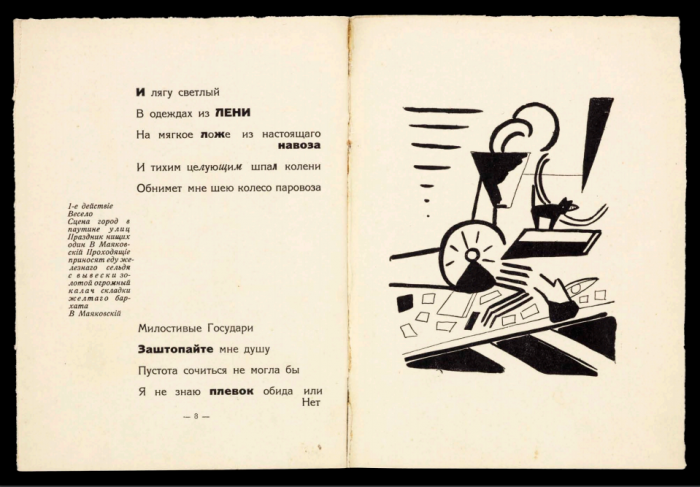

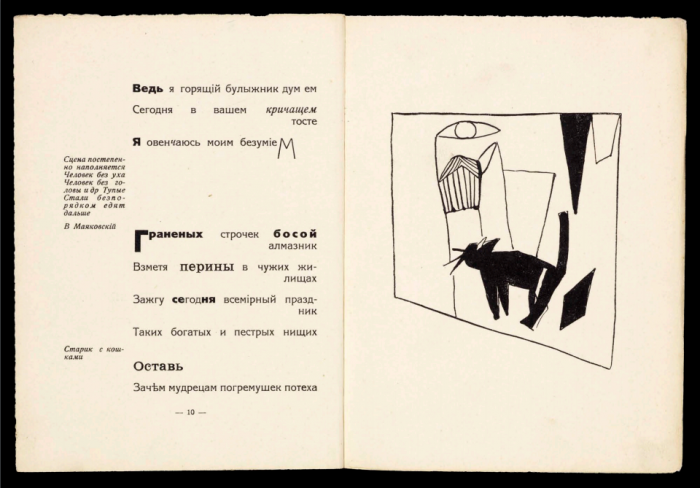

This archive contains about four dozen books by artist/poets like Khlebnikov whose 1914 Old-Fashioned Love; Forestly Boom, you can see pages from at the top of the post. Further up and just above, we see excerpts from Alexei Kruchenykh’s 1913 Vzorval’ (Explodity), a mostly hand-lettered publication with whimsical, dynamic drawings alternating with and surrounding the text. You’ll find over four dozen of these books at the Getty Research Institute. As you browse or search their catalogue, then click on an entry, you’ll want to click on the “View Online” button to see scanned images.

Each of these books—like Vladimir Mayakovsky’s 1913 play, Vladimir Mayakovsky: A Tragedy, above and below—makes a forceful visual impression even if we cannot understand the text. But in many ways, this is beside the point. Zaum poetry was meant to be heard as sound, not sense, and looked at as a physical artifact. Perloff’s book, writes the Getty, “uncovers a wide-ranging legacy in the midcentury global movement of sound and concrete poetry (the Brazilian Noigandres group, Ian Hamilton Finlay, and Henri Chopin), contemporary Western conceptual art, and the artist’s book.” In many ways, these artists represent a parallel tradition in modernism to the one we generally learn of in Western Europe and the U.S., and one just as rich and fascinating.

Related Content:

Hear Russian Futurist Vladimir Mayakovsky Read His Strange & Visceral Poetry

Hear the Experimental Music of the Dada Movement: Avant-Garde Sounds from a Century Ago

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Judging upon the introduction to this article, one would believe the author thinks Communism is the most AWESOME thing since unsliced bread (which you have to wait in line all day for, until supplies run-out)!

No. The author says, “In the early days of the Revolution, one of the most influential forms of expression, Russian Futurism, brought its avant-gardism to the masses, and praised the Revolution while formally challenging every received idea or doctrine.”

Obviously it’s not the politics but the boldness and scope of the art and creativity in these books that are the AWESOME things.

It’s quite possible to ignore the Communist propaganda they might contain and still be in awe of their beauty. It’s like looking at a 1000-year-old Koran, or an illustrated Bible from the same period. You can appreciate the beauty of how it is presented and constructed without having to buy into the religious perspective.

AWESOME Communism ism ism ism ism AWE AWE SOME some somE

(Some read to expand their horizons, some dislike that)