Unsettling historical parallels between the newly-developing world order and the terrors that scourged Europe in the 1930s and 40s now seem undeniable to most informed observers of contemporary geopolitics. Europeans have their own political crises to weather, but all eyes currently seem trained on the military behemoth that is my own country. “These are not normal times,” admits Jane Chong at Lawfare. Though she critiques Nazi comparisons as needlessly alarmist, she “sees no reason for optimism.” While references to history’s greatest villain abound, we’ve also seen Australian scientist Alan Finkel compare the U.S. leader to Joseph Stalin for the suppression and censorship of environmental data.

The devastation Hitler and Stalin visited upon Western and Eastern Europe can hardly be overstated—and we still find it nearly impossible to comprehend. But not soon after the end of World War II, one of the 20th century’s most probing analysts of political thought attempted to do just that.

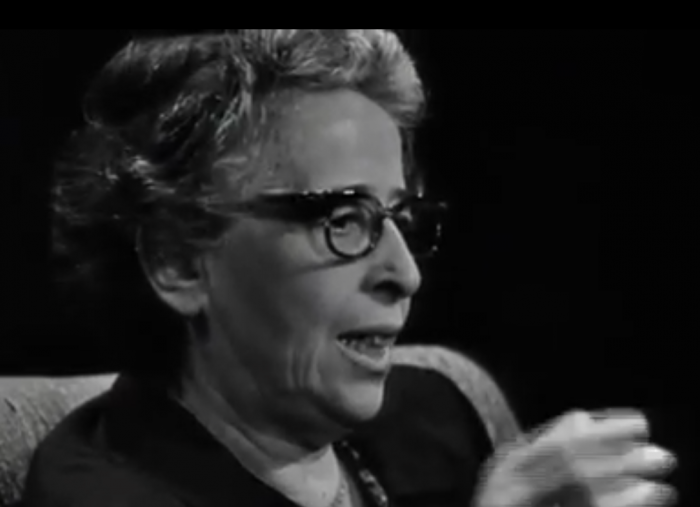

Hannah Arendt’s 1951 The Origins of Totalitarianism remains one of “several seminal works on tyranny and oppression that have recently gained popularity among readers,” notes Alison Griswold at Quartz. And Arendt’s 1963 classic Eichmann in Jerusalem also continues to inform the moment, offering a “sobering reflection,” writes Maria Popova, on what Arendt called “the fearsome, word-and-thought-defying banality of evil.”

Arendt’s renewed relevance recently prompted Melvyn Bragg, host of the excellent BBC Radio program In Our Time, to bring three guest philosophy professors—Robert Eaglestone, Frisbee Sheffield, and Lyndsey Stonebridge—on air to discuss her ideas and influence. Bragg begins with a brief outline of Arendt’s biography, then turns to Sheffield, a lecturer at Girton College, Cambridge, for elaboration. They immediately address one of the most controversial aspects of Arendt’s young life, her affair with her mentor, Martin Heidegger, who joined the Nazi party and remained a true believer in its ideology.

But the conversation quickly moves on from there to encompass Arendt’s multi-dimensional thought. “There’s a great range to her writings,” says Sheffield. A trained classicist, Arendt wrote her dissertation on the idea of love in St. Augustine. Her most philosophical work, The Human Condition, drew on classical concepts to rank human activity into a hierarchy of labor, work, and action. She “wrote on a great range of topics,” Sheffield notes, though “there is a consistent interest in politics and political themes throughout her work.”

Yet Arendt rejected the label of political philosopher and is herself “hard to pin down” politically. Her 1963 book On Revolution, critiqued leftist and Marxist thought and praised the American Revolution for its constitutionalism. She was skeptical of the notion of universal human rights, and her essay On Violence made the argument that violence appears only in the absence of political power, not its ascendency. As we learn from listening to Bragg’s assembled panel of guests, Arendt consistently emphasized two classical concepts: the value of a civic and political order and the importance of the “life of the mind,” also the title of a two-volume work published posthumously in 1978.

In Our Time’s short, lively conversation provides an excellent introduction to Arendt’s life and work. To dive more deeply into the Arendt corpus, visit Bard College’s Hannah Arendt Center for Politics and Humanities, browse the Library of Congress’s Hannah Arendt Papers, and read Lyndsey Stonebridge’s short online essay “Hannah Arendt’s Refugee History.” You’ll also find an extensive reading list of primary and secondary sources at the In Our Time BBC page.

Related Content:

Hannah Arendt Discusses Philosophy, Politics & Eichmann in Rare 1964 TV Interview

Hannah Arendt’s Original Articles on “the Banality of Evil” in the New Yorker Archive

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply