Central to Michel Foucault’s theory of “governmentality” is what he calls “biopower,” an “explosion of numerous and diverse techniques for achieving the subjugations of bodies and the control of populations.” Where debates over abortion and contraception generally coalesce around questions of religion and rights, the French theorist of power saw these issues as part of the bio-political struggle between “governing the self” and “governing others.”

Those who resist repressive biopower seize on the former definition of government. Take a very pointed example of both restrictive government biopower and creative resistance to the same: the 1968 Birth Control Handbook you see here, printed illegally by undergraduate students at Montreal’s McGill University. At the time of this text’s creation, notes Atlas Obscura, “under Canada’s Criminal Code, the dissemination, sale, and advertisement of birth control methods were all illegal, and abortion was punishable by life imprisonment.”

Despite facing the possible consequences of up to two years in prison, the McGill Student Society “sold millions of copies” of The Birth Control Handbook, writes Amanda Edgley, “in Canada and internationally.” Maya Koropatnitsky describes the tremendous social impact of the handbook:

Students at McGill as well as other Quebec campuses snapped up the first run of 17,000 copies. Due to its major success, the committee came out with a second issue of the handbook in 1969. This handbook is seen to be a major player in women’s liberation because it gave young women the knowledge and the ability to control reproductive functions.

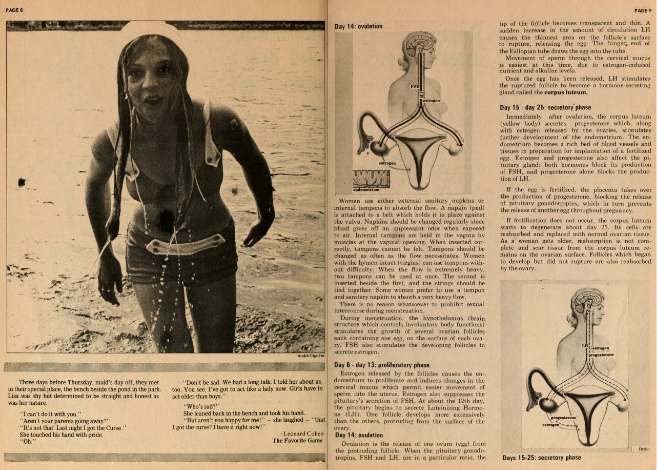

The handbook furthermore “mobilized women into forming meetings and groups to talk about consciousness-raising issues.” This informal education was invaluable for millions of women, who were “desperate for this information,” writes author Laura Kaplan, “so starved for information. You wanted it, in as much detail as you could get it, as graphic as it could be made.”

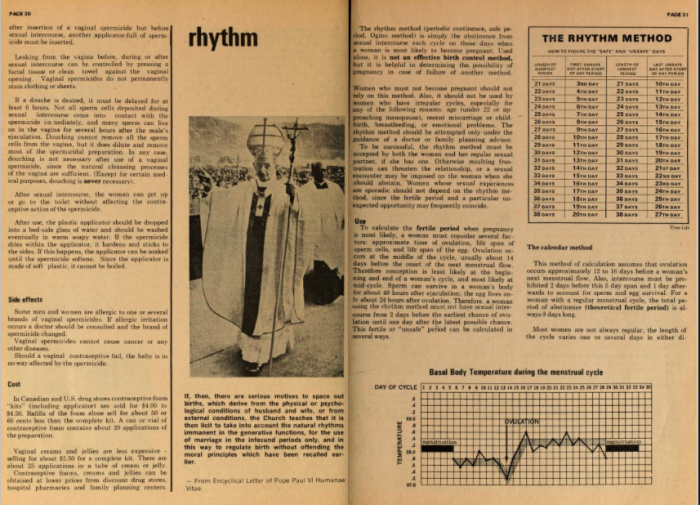

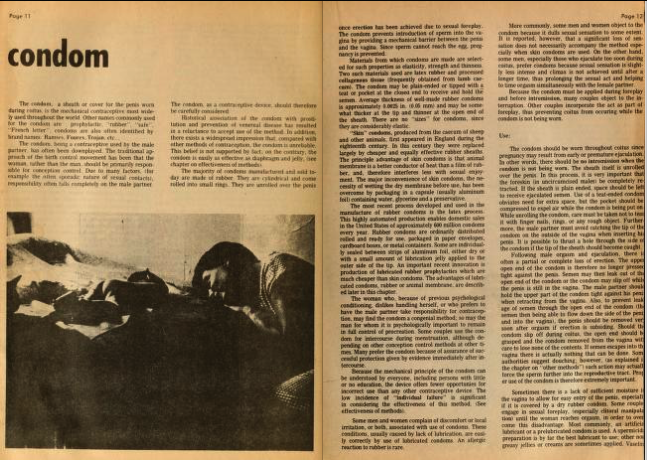

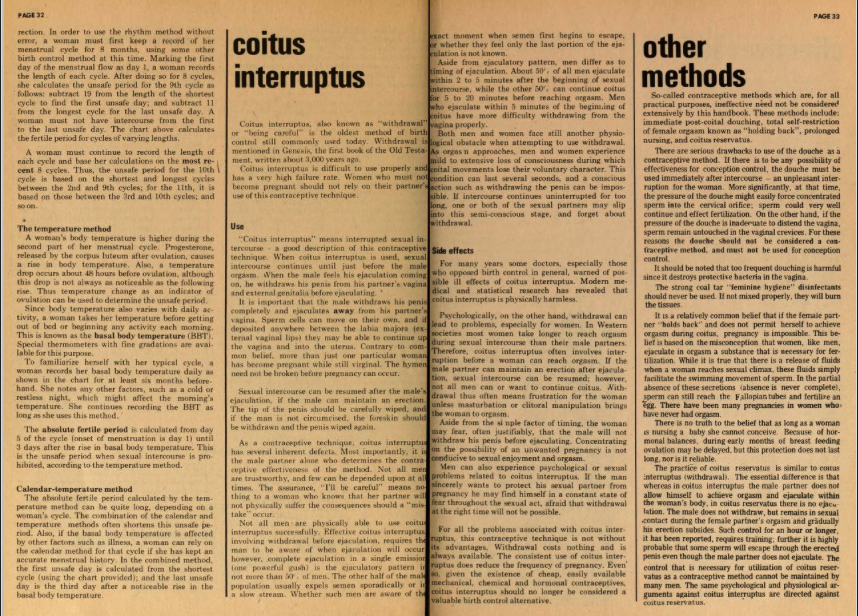

What the Canadian, and U.S., governments saw as sexually explicit will look to us like standard biology textbook illustrations, mundane charts and graphs, ordinary pictures of the birth experience, and tasteful, rather tame nude photos. Original authors Allan Feingold and Donna Cherniak “pored through books in the medical library,” Atlas Obscura writes, “and consulted medical advisors, compiling detailed information on topics like sexual intercourse, menstrual cycles, surgical abortion techniques (accompanied by prices and statistics), and how, exactly, to contact abortion providers.”

Illustrating another Foucauldian insight into the relationship between knowledge and power, not only were birth control methods under the strict control of mostly male doctors (and only available with permission from a husband), but even basic information on reproduction and birth control was difficult for most women to access. “To have all the information on the various methods of birth control in one place,” says Kaplan, “with pros and cons and what you needed to know about them, was a revelation.” Cherniak later remembered, “We joked that after the Bible, we were probably one of the most widely distributed publications in Canada.”

Both editions of the handbook addressed the controversial topic of abortion, citing the Canadian criminal code along the way. “Concerned with the problem of illegal abortion,” writes University of Ottowa professor Christabelle Sethna, “the council mandated the publication” of the handbook, which also “contained editorial commentary that took Western population-control experts to task for their racism and that supported women’s reproductive rights as a function of women’s liberation.” Sethna situates The Birth Control Handbook within a much larger Canadian movement, just “one of the ways,” writes Edgeley, “Canadians took control over their own bodies.” Its creators saw it as a means of changing the world. “Those were the years,” Cherniak says, “in which you thought you could do anything.”

Two years after the first print run of The Birth Control Handbook, the ur-text of feminist bio-politics, Our Bodies, Ourselves, was published by the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective. This book “became its own widely circulated women’s health text,” Atlas Obscura writes, “translated into 29 languages.” But while Our Bodies, Ourselves remains famous for its key role in spreading much-needed information about reproductive health, “its Canadian counterpart has been mostly forgotten.” The Birth Control Handbook gave millions of women the information they needed to govern their own lives. Rediscover the complete text of the first, 1968 edition and second, 1969 edition at the Internet Archive, where you can see a scan, read transcribed full text, and download PDF, Kindle, and other formats.

via Atlas Obscura

Related Content:

Download All 239 Issues of Landmark UK Feminist Magazine Spare Rib Free Online

Simone de Beauvoir Explains “Why I’m a Feminist” in a Rare TV Interview (1975)

The Story Of Menstruation: Watch Walt Disney’s Sex Ed Film from 1946

Watch Family Planning, Walt Disney’s 1967 Sex Ed Production, Starring Donald Duck

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Hmm. So that’s how feminists lost their dignity and self-respect!

Wonderful, that this is preserved — and the info given to later generations.

When we began with women´ s movement end of 1960s, we did not know that there have been at least 3 of such movements before.

wow nice i was exacting after here this.

At Burnaby South High School, in 1971, the student council got copies of the HANDBOOK from SFU Student Society, and despite attempts by the school Administration to prevent it, gave out copies to all the Grade 11 and 12 students. I was the Council President at the time.