By the early 6th century, the Western Roman Empire had effectively come to an end after the deposition of the final emperor and the installation of Germanic kings. Under the second such ruler, Theodoric the Great, emerged one of the most influential works of literature of the European Middle Ages: The Consolation of Philosophy. Its author, senator and philosopher Boethius, wrote the text while imprisoned and awaiting execution.

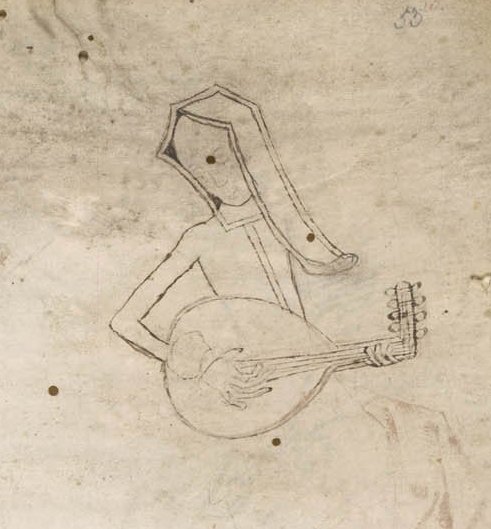

A conversation the despondent author has with his muse, Lady Philosophy, the book seeks the nature of happiness and the nature of God, in the midst of great loss, disgrace, and tyranny. The Consolation of Philosophy belongs to a long tradition of prison literature that extends to Don Quixote, “Civil Disobedience,” and “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” Almost a thousand years after Boethius’s 524 execution, one late Medieval reader of his book—perhaps inspired by the text, or not—left the drawing you see above on the last page of a 15th century English illuminated manuscript.

Such doodling was common practice at the time, notes Medieval book historian Erik Kwakkel. Blank pages in manuscripts “often filled up with pen trials, notes, doodles, or drawings.” But this particular doodle “is not what you’d expect: a full-on drawing of a maiden playing the lute, which she holds just like a guitar.” Boethius may have dismissed poetry in his search for happiness in the midst of despair, but his literary efforts might put us in mind of poet Berthold Brecht, who famously wrote while in exile from Germany in the 1930s, “In the dark times/Will there also be singing? Yes, there will also be singing/About the dark times.”

As if to remind us of the necessity not only of philosophy, but also of song in dark times, our anonymous reader drew a “rockstar lady,” whose pose connotes nothing but pure joy. We could juxtapose her with the joyful guitar poses of any number of modern blues and rock stars, who have played through any number of dark times. The drawing appears in a translation by John Walton dating from between 1410 and 1500, a century in Europe with no shortage of its own political crises and tyrannical rulers. “Even in the darkest of times,” wrote Hannah Arendt in her essay collection profiling artists and writers like Boethius and Brecht, “we have the right to expect some illumination,” whether from philosophy or poetry. We also have the right—the medieval doodler in Boethius’ book seemed to suggest some 500-odd years ago—to rock out.

via Erik Kwakkel

Related Content:

Wearable Books: In Medieval Times, They Took Old Manuscripts & Turned Them into Clothes

Wonderfully Weird & Ingenious Medieval Books

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Lady Philosophy?