Like most artists, Emmanuel Radnitzky had more than one major interest in his life. We who know him as Man Ray usually first encounter him through his photography, such as the artist and writer portraits featured here at Open Culture last year. But Man Ray himself ultimately considered painting his main creative field. And, apart from his work, he had chess–or at least his friend and fellow conceptual artist Marcel Duchamp had chess. Duchamp seems to have turned Man Ray on to it as well, and they even appear playing together in Rene Clair’s 1924 film Entr’acte.

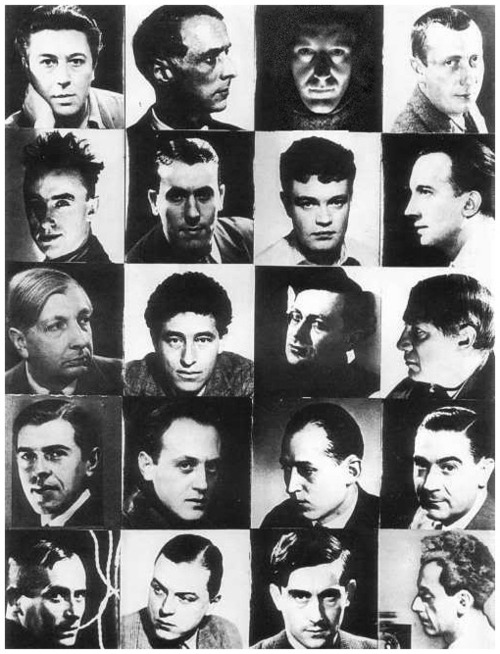

Duchamp’s passion for chess ran deep enough that, for a time, he all but abandoned art to devote himself to the game. Later he came to the realization that “chess was art; art was chess,” having pursued both of those interests at once in the creation of an art deco chessboard. Man Ray, for his part, brought art and chess together in 1934’s Surrealist Chessboard, a mosaic of his portraits of artists associated with the Surrealist movement, including Salvador Dalí, Andre Breton, Pablo Picasso, René Magritte, Joan Miró, and of course himself — but with the chess-loving Duchamp nowhere to be seen.

“Surrealist exhibition group photographs include the frequent participation of Man Ray but rarely Duchamp,” writes Lewis Kachur in aka Marcel Duchamp: Meditations on the Identities of an Artist, his non-appearance on the Surrealist Chessboard being the “most astonishing” example. “The structure is the democratic grid format of the chessboard, with each of twenty surrealists or fellow travelers as a head shot against a black or light-colored background, alternating to suggest the black and white squares of the board. Man Ray had a negative of an appropriate profile bust of Duchamp (1930), striking for its absence here.”

Kachur imagines that Duchamp “chose not to take part,” in keeping with his “somewhat shadowy” position in relation to the Surrealists, “on the margins of the movement group’s identity.” Or he may simply have wanted to save his friend the trouble of figuring out a shape in which to arrange 21 portraits instead of 20. Whatever Duchamp thought of this project that used the chessboard only as visual structure, he probably preferred the chess set Man Ray designed a decade earlier using historically inspired pure geometric forms — and one that he could actually play chess with. You can still purchase own copy of that chess set today.

Related Content:

Man Ray’s Portraits of Ernest Hemingway, Ezra Pound, Marcel Duchamp & Many Other 1920s Icons

Man Ray and the Cinéma Pur: Four Surrealist Films From the 1920s

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Midnight in Paris is excellent film for HollyWoody look at the group.