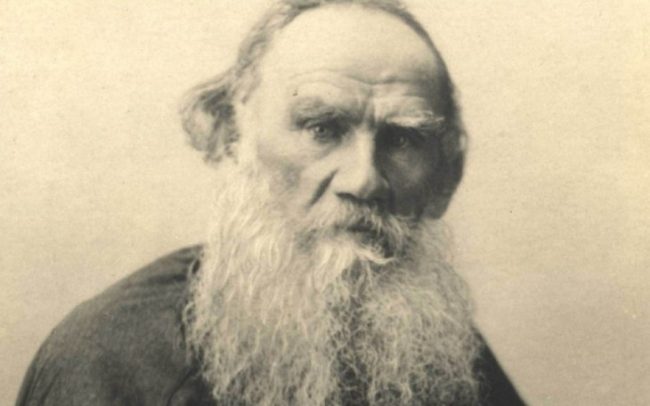

Leo Tolstoy is remembered as both a towering pinnacle of Russian literature and a fascinating example of Christian anarchism, a mystical version of which the aristocratic author pioneered in the last quarter century of his life. After a dramatic conversion, Tolstoy rejected his social position, the favored vices of his youth, and the dietary habits of his culture, becoming a vocal proponent of vegetarianism in his ascetic quest for the good life. Thousands of his contemporaries found Tolstoy’s example deeply compelling, and several communes formed around his principles, to his dismay. “To speak of ‘Tolstoyism,’” he wrote, “to seek guidance, to inquire about my solution of questions, is a great and gross error.”

“Still,” writes Kelsey Osgood at The New Yorker, “people insisted on seeking guidance from him,” including a young Mahatma Gandhi, who struck up a lively correspondence with the writer and in 1910 founded a community called “Tolstoy Farm” near Johannesburg.

Though uneasy in the role of movement leader, the author of Anna Karenina invited such treatment by publishing dozens of philosophical and theological works, many of them in opposition to a contrary strain of religious and moral ideas developing in the late nineteenth century. Often called “muscular Christianity,” this trend responded to what many Victorians thought of as a crisis of masculinity by emphasizing sports and warrior ideals and railing against the “feminization” of the culture.

Tolstoy might be said to represent a “vegetable Christianity”—seeking harmony with nature and turning away from all forms of violence, including the eating of meat. In “The First Step,” an 1891 essay on diet and ethical commitment, he characterized the prevailing religious attitude toward food:

I remember how, with pride at his originality, an Evangelical preacher, who was attacking monastic asceticism, once said to me “Ours is not a Christianity of fasting and privations, but of beefsteaks.” Christianity, or virtue in general—and beefsteaks!

While he confessed himself “not horrified by this association,” it is only because “there is no bad odor, no sound, no monstrosity, to which man cannot become so accustomed that he ceases to remark what would strike a man unaccustomed to it.” The killing and eating of animals, Tolstoy came to believe, is a horror to which—like war and serfdom—his culture had grown far too accustomed. Like many an animal rights activist today, Tolstoy conveyed his horror of meat-eating by describing a slaughterhouse in detail, concluding:

[I]f he be really and seriously seeking to live a good life, the first thing from which he will abstain will always be the use of animal food, because, to say nothing of the excitation of the passions caused by such food, its use is simply immoral, as it involves the performance of an act which is contrary to the moral feeling—killing.

[W]e cannot pretend that we do not know this. We are not ostriches, and cannot believe that if we refuse to look at what we do not wish to see, it will not exist.… [Y]oung, kind, undepraved people—especially women and girls—without knowing how it logically follows, feel that virtue is incompatible with beefsteaks, and, as soon as they wish to be good, give up eating flesh.

The idea of vegetarianism of course preceded Tolstoy by hundreds of years of Hindu and Buddhist practice. And its growing popularity in Europe and America preceded him as well. “Tolstoy became an outspoken vegetarian at the age of 50,” writes Sam Pavlenko, “after meeting the positivist and vegetarian William Frey, who, according to Tolstoy’s son Sergei Lvovich, visited the great writer in the autumn of 1885.” Tolstoy’s dietary stance fit in with what Charlotte Alston describes as an “increasingly organized” international vegetarian movement taking shape in the late nineteenth century.

Like Tolstoy in “The First Step,” proponents of vegetarianism argued not only against cruelty to animals, but also against “the brutalization of those who worked in the meat industry, as butchers, slaughtermen, and even shepherds and drovers.” But vegetarianism was only one part of Tolstoy’s religious philosophy, which also included chastity, temperance, the rejection of private property, and “a complete refusal to participate in violence or coercion of any kind.” This marked his dietary practice as distinct from many contemporaries. Tolstoy and his followers “made the link between vegetarianism and a wider humanitarianism explicit.”

“How was it possible,” Alston summarizes, “to regard the killing of animals for food as evil, but not to condemn the killing of men through war and capital punishment? Not all members of the vegetarian movement agreed.” Some saw “no connection between the questions of war and diet.” Tolstoy’s philosophical argument against all forms of violence was not original to him, but it resonated all over the world with those who saw him as a shining example, including his two daughters and eventually his wife Sophia, who all adopted the practice of vegetarianism. A book of their recipes was published in 1874, and adapted by Pavlenko for his Leo Tolstoy: A Vegetarian’s Tale. (See one example here—a family recipe for macaroni and cheese.)

In her study Tolstoy and His Disciples, Alston details the Russian great’s wide influence through not only his diet but the totality of his spiritual practices and unique political and religious views. Interestingly, unlike many animal rights activists of his day and ours, Tolstoy refused to endorse legislation to punish animal cruelty, believing that punishment would only result in the perpetuation of violence. “Non-violence, non-resistance and brotherhood were the principles that lay at the basis of Tolstoyan vegetarianism,” she observes, “and while these principles meant that Tolstoyans cooperated closely with vegetarians, they also kept them in many ways apart.”

Related Content:

Leo Tolstoy’s Family Recipe for Macaroni and Cheese

Watch Glass Walls, Paul McCartney’s Case for Going Vegetarian

Leo Tolstoy’s Masochistic Diary: I Am Guilty of “Sloth,” “Cowardice” & “Sissiness” (1851)

Leo Tolstoy Creates a List of the 50+ Books That Influenced Him Most (1891)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Tolstoy’s change of heart is a fascinating moment in the history of vegetarianism, but (as you acknowledge) there was already a lively vegetarian scene, at least in the UK where Gandhi had been confirmed in his vegetarianism by diet reformers like Henry Salt.

If you’re interested in the backstory to today’s vegetarian and vegan movement, you might enjoy my radio series “Vegetarianism: The Story So Far”.

It’s an epic history of opposition to flesh-eating starting in ancient India and Greece and, in 15 episodes, tracking the whole course of the story. I interview expert historians, bring the characters to life with the help of actors, and visit some of the places the story unfolded.

You can listen at:

http://theVeganOption.org/veghist

It’s been very well received. Dr Tushar Mehta said it was “very accurate and excellent”. Colleen Patrick-Goudreau told me she “Loved the episode”. So I think it’s worth a click :).

Most Christians argue for flesh diet. This example of Seneca shows that their original diet was flesh-free. Seneca used to be a vegetarian for some time but when it became suspicious due to its relationship with Jews (Christians), he returned to eating flesh:

“Now, Sextius abstained upon another account, which was, that he would not have men inured to hardness of heart by the laceration and tormenting of living creatures; besides, that Nature had sufficiently provided for the sustenance of

mankind without blood.” This wrought so far upon me that I gave over eating of flesh, and in one year I made it not only easy to me but pleasant; my mind methought was more at liberty (and I am still of the same opinion), but I gave it over nevertheless; and the reason was this: it was imputed as a superstition to the Jews, the forbearance of

some sorts of flesh, and my father brought me back again to my old custom, that I might not be thought tainted with their superstition.” (Morals, page 110–111)