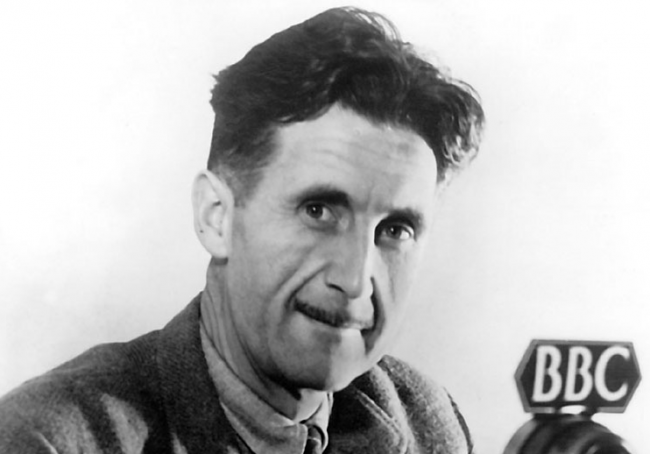

Image via Wikimedia Commons

Say you find yourself in a one-party state that promises to dismantle every civil institution you believe in and trample every ethical principle you hold dear. You may feel a little despondent. While a “this too shall pass” attitude may help you gain perspective, the problem isn’t simply that you’re on the losing side of a political contest. As George Orwell wrote in 1984, total authoritarian control means that “Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.” The epistemic baseline you took for granted may become increasingly, frighteningly elusive as the ruling party reshapes all of reality to its designs.

With more vivid clarity than perhaps anyone since, Orwell characterized the mechanisms by which totalitarianism takes hold. His 1948 novel has not only given us a near-universal set of terms to describe the phenomenon, but it also gives us a metric: when our society begins to resemble Orwell’s dystopia in pervasive and alarming ways, we should know without question things have gone badly wrong. Whether we can do much about it is another question, but we should remember that Orwell himself was not simply an armchair observer of Fascism, Soviet totalitarianism, or oppressive English colonial rule. He fought Franco’s forces in Spain during the Spanish Civil War and as a journalist wrote critical articles and essays exposing hypocrisies and abuses of law and language. The impact of his work on later generations speaks for itself.

In the CBC radio documentary The Orwell Tapes, in three parts here, we have a comprehensive introduction to Orwell’s work, thought, and life. It opens with alarming soundbites from lightning rods (and villains or heroes, depending on who you ask) Julian Assange and Edward Snowden. But it doesn’t stray into the clichéd territory of overheated conspiracy those names often inspire. Instead we’re largely treated throughout each episode to firsthand accounts of the subject from those who knew him well.

“CBC is the only media organization in the world,” says host Paul Kennedy, “with a comprehensive archive of recordings featuring people who knew Orwell, from his earliest days, to his final moments. 75 people, 50 hours of recordings.” Edited snippets of these audio recordings make up the bulk of The Orwell Tapes, hence the title, making the program oral history rather than sensationalism. The interviewees include friends, former girlfriends, comrades-in-arms, and critical opponents. Each episode’s page on the CBC site features a list of names and relations to Orwell at the bottom.

But of course, accusations of sensationalism always follow those who warn of Orwellian trends and tendencies. Like many of our contemporaries, Orwell was a contradictory figure. He served as a colonial policeman in Burma even as he grew disgusted with Empire; he considered himself a Democratic Socialist, but he never looked away from the authoritarian horrors of state communism; and he has been held up as a pillar of resistance to state surveillance and control, even as he also stands accused of “naming names.” But the overall impression we get from Orwell’s friends and colleagues is that he was fully committed—to writing, to political engagement, to telling the truth as he saw it.

In releasing The Orwell Tapes this month, the CBC gives us five reasons why Orwell “is still very much with us today.” Some of these—modern surveillance, the corruptions of power (and the power of corruption)—will be familiar, as will number 3, a variation on what we’ve come to call “empathy” for one’s opponent. The 4th reason, CBC notes, is the renewed relevance of socialism as a viable alternative to capitalist predation. And finally, we have the continued danger of speaking truth to power, and to those who serve it religiously, uncritically, and often violently. As Orwell wrote in the preface to Animal Farm, “If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they don’t want to hear.”

Related Content:

Huxley to Orwell: My Hellish Vision of the Future is Better Than Yours (1949)

George Orwell’s Six Rules for Writing Clear and Tight Prose

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply