The recent hit film Arrival took on a question that has, in recent decades, deeply concerned those involved in the search for intelligent life elsewhere in the universe. Say we locate that intelligent life. Say we decide what we want to say. On what basis, then, do we figure out how to say it? Aliens, while they may well have evolved certain qualities in common with us humans, probably haven’t happened to come up with any of the same spoken or written languages we have.

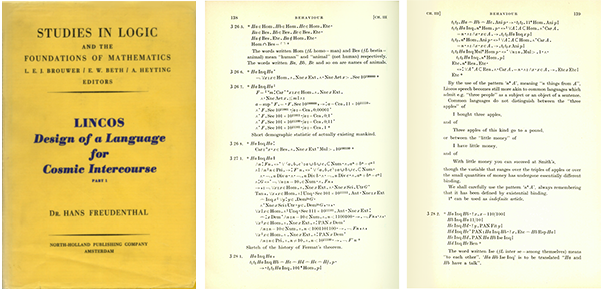

In 1960, the Dutch mathematician Hans Freudenthal came up with a solution: why not create a language they could learn? The efforts came published in the book Lincos: Design of a Language for Cosmic Intercourse. In it, writes The Atlantic’s Daniel Oberhaus, “Freudenthal announced that his primary purpose ‘is to design a language that can be understood by a person not acquainted with any of our natural languages, or even their syntactic structures … The messages communicated by means of this language [contain] not only mathematics, but in principle the whole bulk of our knowledge.’ ”

Freudenthal created Lincos as a kind of spoken language “made up of unmodulated radio waves of varying length and duration, encoded with a hodgepodge of symbols borrowed from mathematics, science, symbolic logic, and Latin. In their various combinations, these waves can be used to communicate anything from basic mathematical equations to explanations for abstract concepts like death and love.” You can read Lincos: Design of a Language for Cosmic Intercourse (PDF), over at Monoskop, and even though it constitutes only the first of a planned series of books Freudenthal never finished, you can still learn the basics of Lincos from it.

Be warned, however, of the intellectual challenge ahead: Freudenthal just plows ahead without even defining many of the concepts, which readers without a background in mathematics or logic will likely need explained, and Oberhaus quotes even one astrophysicist as calling Freudenthal’s book “the most boring I have ever read. Logarithm tables are cool compared to it.” Still, 56 years on from its creation, this intergalactic Esperanto has had a kind of influence: Freudenthal demonstrated the idea of including an intuitively understandable dictionary in the spaceward-sent message itself, an idea Carl Sagan went on to use in his novel Contact, in which extraterrestrial intelligence-seeking astronomers receive a signal from elsewhere that considerately does the same.

Contact became a major motion picture, something of the Arrival of its day, in 1997. Two years later, a couple of Canadian Defense Research Establishment astrophysicists used a radio telescope to beam out a Lincos-encoded message toward a few close stars. Like any enthusiastic member of their profession would, they sent out information about math, physics, and astronomy. They have yet to hear back from any residents, fellow astrophysicists or otherwise, of those distant neighborhoods. But if any extraterrestrials did hear the message, and even if they have yet to fully grasp Lincos, I have to believe they feel at least a little grateful that, unlike some humans attempting to communicate with others unlike them here on Earth, we didn’t just start yammering in English and hope for the best.

via Monoskop

Related Content:

Free NASA eBook Theorizes How We Will Communicate with Aliens

An Animated Carl Sagan Talks with Studs Terkel About Finding Extraterrestrial Life (1985)

Animated Video Explores the Invented Languages of Lord of the Rings, Game of Thrones & Star Trek

Klingon for English Speakers: Sign Up for a Free Course Coming Soon

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply