Arthur Rimbaud, far-seeing prodigy, “has been memorialized in song and story as few in history,” writes Wyatt Mason in an introduction to the poet’s complete works; “the thumbnail of his legend has proved irresistible.” The poet, we often hear, ended his brief but brilliant literary career when he ran off to the Horn of Africa and became a gunrunner… or some other sort of adventurous outlaw character many miles removed, it seems, from the intense symbolist hero of Illuminations and A Season in Hell.

Rimbaud’s break with poetry was so decisive, so abrupt, that critics have spent decades trying to account for what one “hyperbolic assessment” deemed as having “caused more lasting, widespread consternation than the break-up of the Beatles.” What could have caused the young libertine, so drawn to urban voyeurism and the skewering of the local bourgeoisie, to disappear from society for an anonymous, rootless life?

On the other hand, in revisiting the poetry we find—amidst the grotesque, hallucinogenic reveries—that “travel, adventure, and departure on various levels are thematic concerns that run through much of Rimbaud”: from 1871’s “The Drunken Boat” to A Season in Hell’s “Farewell,” in which the poet writes, “The time has come to bury my imagination and my memories! A fitting end for an artist and teller of tales.”

He was only 18 then, in 1873, when he wrote his farewell. Two years later, he would finally end his violent tumultuous relationship with Paul Verlaine, and embark on a series of voyages, first by foot all over Europe, then to the Dutch East Indies, Cyprus, Yemen, and finally Abyssinia (modern day Ethiopia), where he settled in Harar, struck up a friendship with the governor (the father of future Emperor Haile Selassie), and became a highly-regarded coffee trader, and yes, gun dealer.

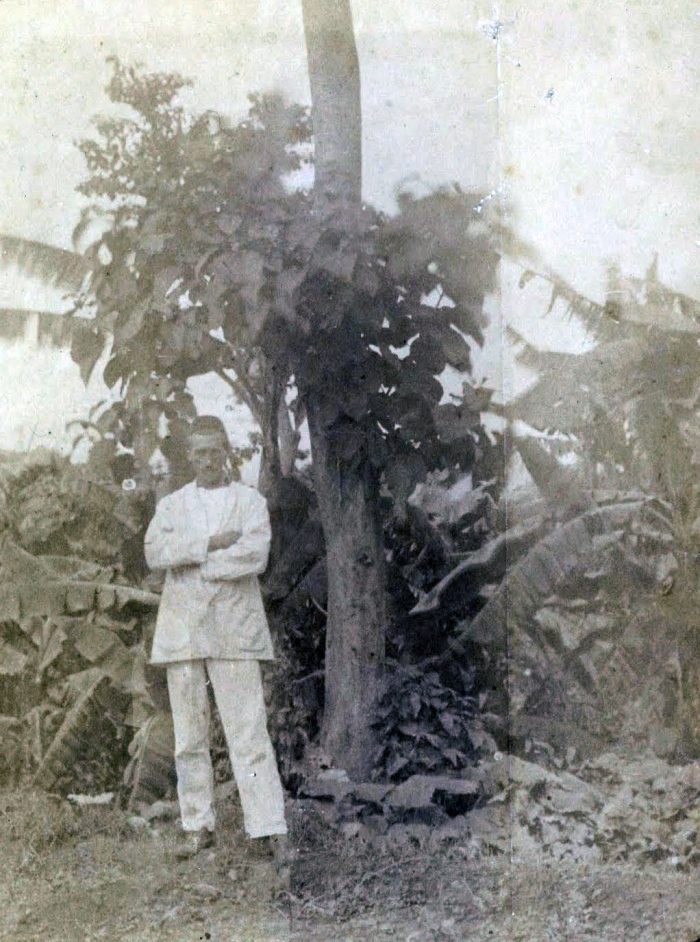

Rimbaud may have left poetry behind, deciding he had realized all he could in language. But he had not given up on approaching his experience aesthetically. Only, instead of trying “to invent new flowers, new stars, new flesh, new tongues,” as he wrote in “Farewell,” he had evidently decided to take the world in on its own terms. He documented his findings in essays on geography and travel accounts and, in 1883, several photographs, including two self-portraits he sent to his mother in May, writing, “Enclosed are two photographs of me which I took.”

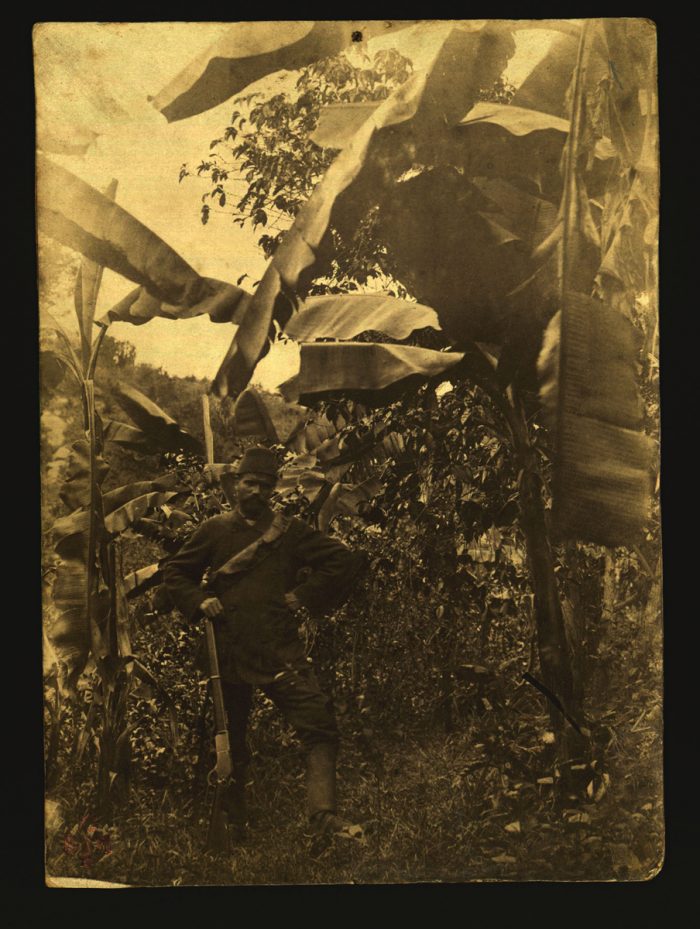

You can see one of those portraits at the top of the post, and the other, in much worse shape, below it, and a third self-portrait just below. The “circumstances in which the photographs were taken are quite mysterious,” writes Lucille Pennel at The Eye of Photography.

Starting in 1882, Rimbaud became fascinated with the new technology. He ordered a camera in Lyon in order to illustrate a book on “Harar and the Gallas country,” a camera he received only in early 1883. He also ordered specialized books and photo processing equipment. The planned scientific publication was never realized, and the six photographs are the only trace of Rimbaud’s activity.

“I am not yet well established, nor aware of things,” Rimbaud wrote in the letter to his mother, “But I will be soon, and I will send you some interesting things.” It’s not exactly clear why Rimbaud abandoned his photographic endeavors. He had approached the pursuit not only as hobby, but also as a commercial venture, writing in his letter, “Here everyone wants to be photographed. They even offer one guinea a photograph.”

The comment leads Pennel to conclude “there must have been other photographs, but any trace of them is lost, raising doubts about the degree of Rimbaud’s engagement with photography.”

Perhaps, however, he’d simply decided that he’d done all he could do with the medium, and let it go with a graceful farewell. History, posterity, the cementing of a reputation—these are phenomena that seemed of little interest to Rimbaud. “What will become of the world when you leave?” he had written in “Youth, IV”—“No matter what happens, no trace of now will remain.” In a historical irony, Rimbaud’s photographs “were developed in ‘filthy water,’” notes Pennel, meaning they “will continue to fade until the images are all gone. They are as fleeting as the man with the soles of wind.”

If we wish to see them in person, the time is short. The photo at the top of the post now resides at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. The other six are housed at the Arthur Rimbaud Museum in Charleville-Mézières.

via Vintage Anchor/The Eye of Photography.

Related Content:

The Brief Wondrous Career of Arthur Rimbaud (1870–1874)

Great 19 Century Poems Read in French: Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Verlaine & More

Patti Smith’s Polaroids of Artifacts from Virginia Woolf, Arthur Rimbaud, Roberto Bolaño & More

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

I really enjoy Arthur Rimbaud and All other French Poets, I do have a lot of the Poems, Delicious peace of mind 😁😁😁😁😁😁