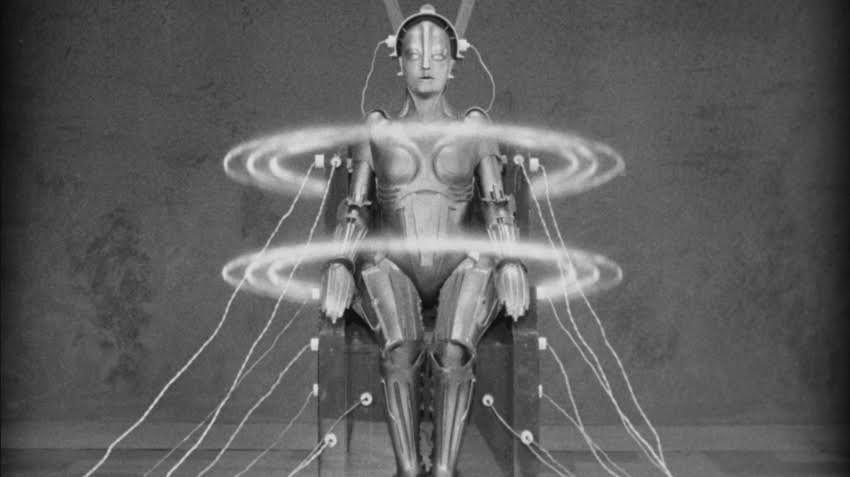

When we watch Fritz Lang’s Metropolis now, we see an aesthetically daring landmark work of science-fiction cinema. When H.G. Wells watched Metropolis back in 1927, the year of its release, he saw something very different indeed. “I have recently seen the silliest film,” wrote the author of The War of the Worlds and The Time Machine as an opener for his New York Times review. “I do not believe it would be possible to make one sillier.”

Despite its giant budget, Metropolis gives “in one eddying concentration almost every possible foolishness, cliché, platitude, and muddlement about mechanical progress and progress in general, served up with a sauce of sentimentality that is all its own.” History remembers Lang and Wells both as visionaries who looked, often with little optimism, to the future, but clearly they had a difference of opinion as to how that future would actually play out.

The scientifically-minded Wells took the impressionistic Metropolis literally, taking issue with — among other things — how its airplanes “show no advance on contemporary types”; its “motor cars are 1926 models or earlier”; its vision of a vertically stratified city look, “to put it mildly, highly improbable”; the apparent condition that the city’s “machines are engaged quite furiously in the mass production of nothing that is ever used”; and the sentimentality of its makers, “who are all on the side of soul and love and such like.”

Metropolis opened to mixed reviews at first (some of which you can read here), but no contemporary critic could match Wells for sheer disdain. “Never for a moment does one believe any of this foolish story; never for a moment is there anything amusing or convincing in its dreary series of strained events,” he wrote, steering his point-by-point takedown to its conclusion. “It is immensely and strangely dull. It is not even to be laughed at.”

Strong stuff, but the highest form of film criticism, as the French New Wave would later articulate, is filmmaking. And so, in 1936, came Things to Come, another cinematic spectacle of the future, this one built to the ostensibly more plausible specifications Wells laid out as its screenwriter — that film itself just one more predecessor to the unending series of dystopias, utopias, and every kind of future in-between to appear on the screen over the next eight decades.

Related Content:

Read the Original 32-Page Program for Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927)

Fritz Lang Invents the Video Phone in Metropolis (1927)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

…so Wells had a bad day…