Orthodox thinkers have not often found the answers to suffering in the Book of Job particularly comforting—an early scribe likely going so far as interpolating the speech of one of Job’s more Pollyannaish friends. The gnarly metaphysical issues raised and never quite resolved strike us so powerfully because of the kinds of things that happen to Job—unimaginable things, excruciatingly painful in every respect, and almost patently impossible, marking them as legend or literary embellishment, at least.

But his ordeal is at the same time believable, consisting of the pains we fear and suffer most—loss of health, wealth, and life. Job is the kind of story we cannot turn away from because of its horrific car-wreck nature. That it supposedly ends happily, with Job fully restored, does not erase the suffering of the first two acts. It is a huge story, cosmic in its scope and stress, and one of the most obviously mythological books in the Bible, with the appearance not only of God and Satan as chatty characters but with cameos from the monsters Behemoth and Leviathan.

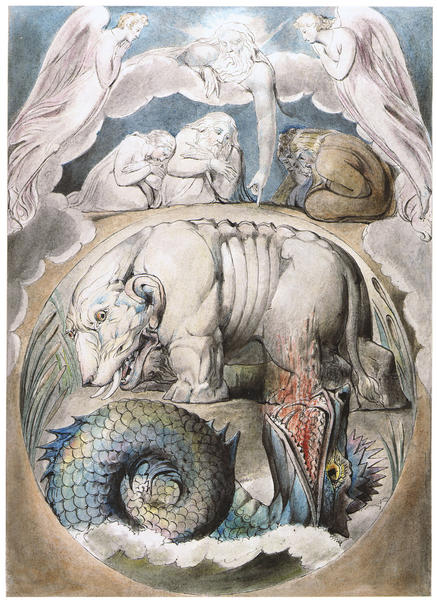

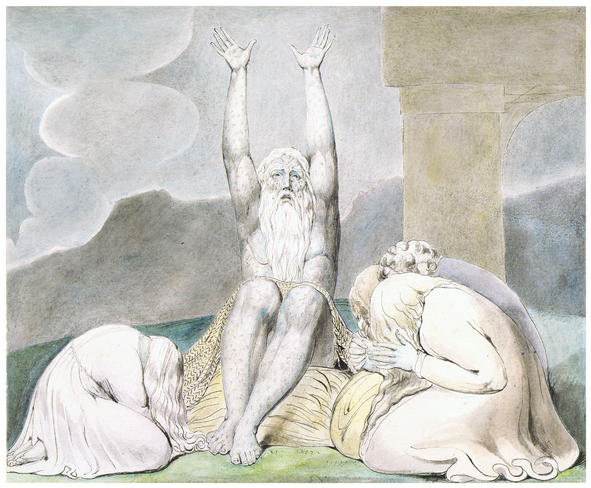

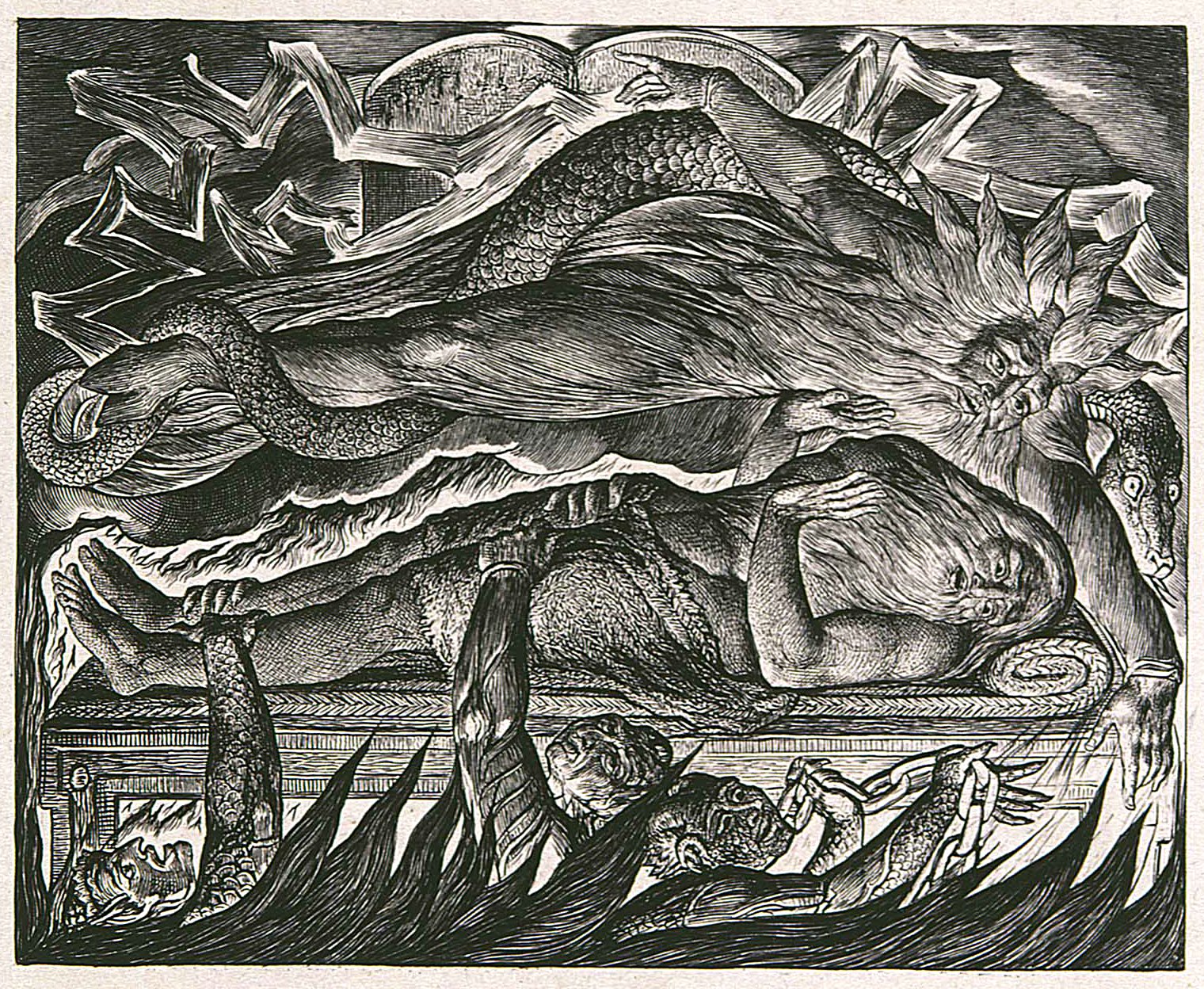

Such a story in its entirety would be very difficult to represent visually without losing the personal psychological impact it has on us. Few, perhaps, could realize it as skillfully as William Blake, who illustrated scenes from Job many times throughout his life. Blake began in the 1790s with some very detailed engravings, such as that at the top of the post from 1793. He then made a series of watercolors for his patrons Thomas Butts and John Linell between 1805 and 1827. These—such as the plate of “Behemoth and Leviathan” further up—give us the mythic scale of Job’s narrative and also, as in “Job’s Despair,” above, the human dimension.

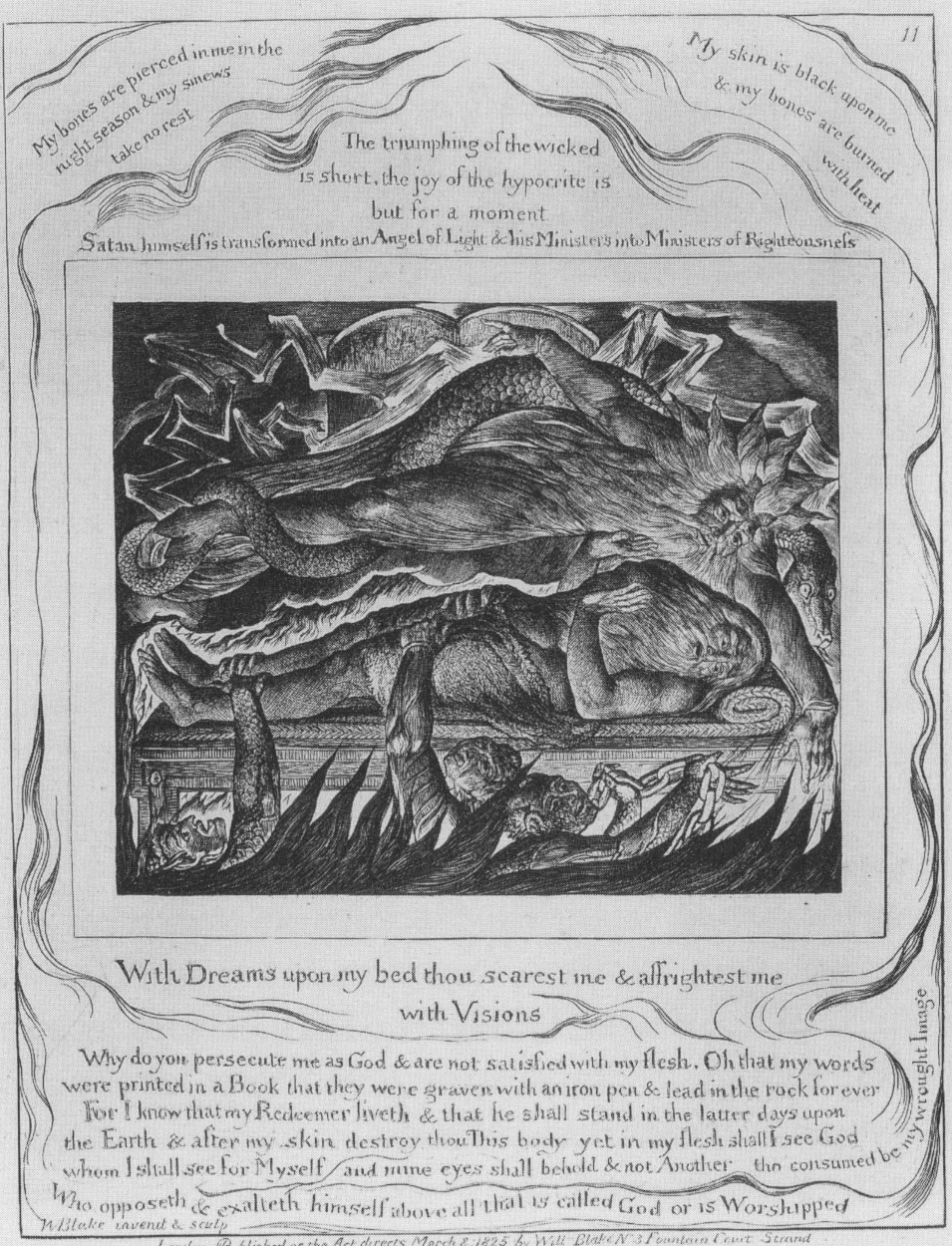

Blake’s final illustrations—a series of 22 engraved prints published in 1826 (see a facsimile here)—“are the culmination of his long pictorial engagement with that biblical subject,” writes the William Blake Archive. They are also the last set of engravings he completed before his death (his Divine Comedy remained unfinished). These illustrations draw closely from his previous watercolors, but add many graphic design elements, and more of Blake’s idiosyncratic interpretation, as in the plate above, which shows us a “horrific vision of a devil-god.” In the full page, below, we see Blake’s marginal glosses of Job’s text, including the line, right above the engraving, “Satan himself is transformed into an Angel of Light & his Ministers into Ministers of Righteousness.”

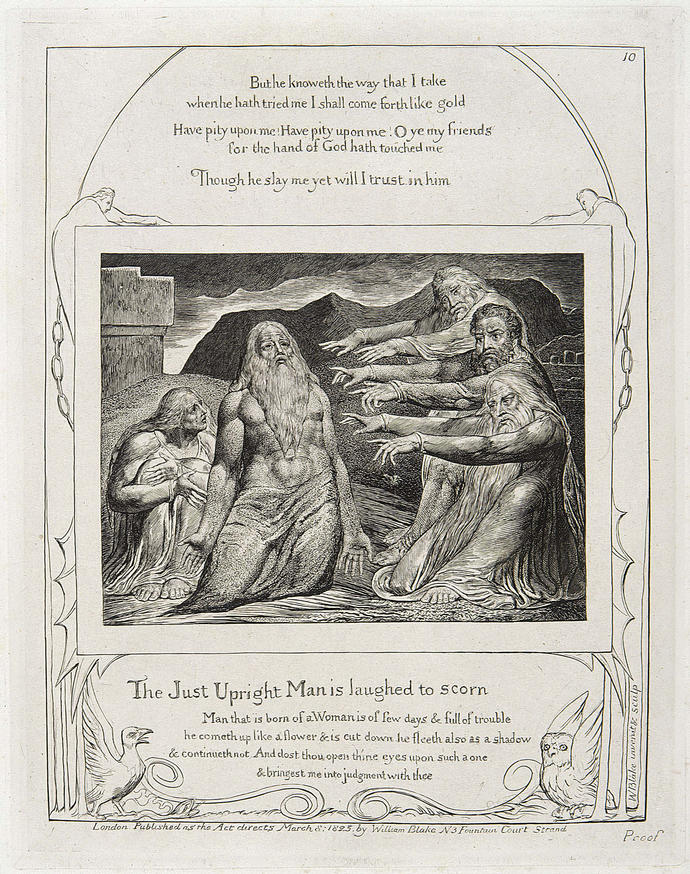

Other pages, like that below of Job and his friends/accusers, take a more conservative approach to the text, but still present us with a strenuous visual reading in which Job’s friends appear far from sympathetic to his terrible plight. It’s a very different image than the one at the top of the post. We know that Blake—who struggled in poverty and anonymity all his life—identified with Job, and the story influenced his own peculiarly allegorical verse. Perhaps Blake’s most famous poem, “The Tyger,” alludes to Job, substituting the “Tyger” for the Behemoth and Leviathan.

The Job paintings and engravings stand out among Blake’s many literary illustrations. They have been almost as influential to painters and visual artists through the years as the Book of Job itself has been on poets and novelists. These final Job engravings, writes the Blake Archive, “are generally considered to be Blake’s masterpiece as an intaglio printmaker.”

Related Content:

William Blake’s Last Work: Illustrations for Dante’s Divine Comedy (1827)

William Blake’s Hallucinatory Illustrations of John Milton’s Paradise Lost

Allen Ginsberg Sings the Poetry of William Blake (1970)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply