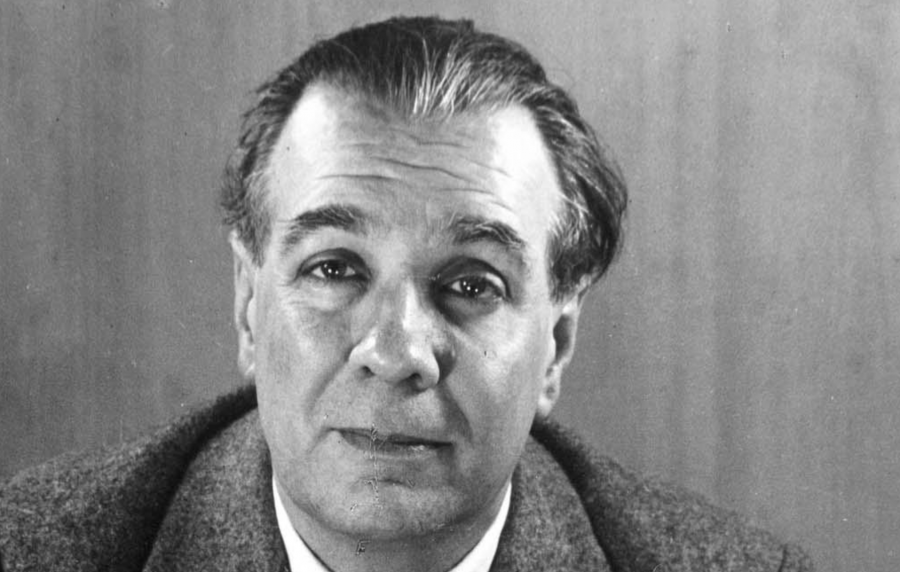

“Jorge Luis Borges 1951, by Grete Stern” via Wikimedia Commons.

When we first read the work of Jorge Luis Borges, we may wish to write like him. When we soon discover that nobody but Borges can write like Borges, we may wish instead that we could have collaborated with him. Once, he and his luminary-of-Argentine-literature colleagues, friend and frequent collaborator Adolfo Bioy Casares and Bioy Casares’ wife Silvina Ocampo, got together to compose a story about a writer from the French countryside. Though they never did finish it, one piece of its content survives: a list of sixteen rules, drawn up by Borges, for the writing of fiction.

Or at least that’s how Bioy Casares told it to the French magazine L’Herne, which reprinted the list. Instead of sixteen recommendations for what a writer of fiction should do, Borges playfully provided a list of sixteen prohibitions–things writers of fiction should never let slip into their work.

- Non-conformist interpretations of famous personalities. For example, describing Don Juan’s misogyny, etc.

- Grossly dissimilar or contradictory twosomes like, for example, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, Sherlock Holmes and Watson.

- The habit of defining characters by their obsessions; like Dickens does, for example.

- In developing the plot, resorting to extravagant games with time and space in the manner of Faulkner, Borges, and Bioy Casares.

- In poetry, characters or situations with which the reader can identify.

- Characters prone to becoming myths.

- Phrases, scenes intentionally linked to a specific time or a specific epoch; in other words, local flavor.

- Chaotic enumeration.

- Metaphors in general, and visual metaphors in particular. Even more concretely, agricultural, naval or banking metaphors. Absolutely un-advisable example: Proust.

- Anthropomorphism

- The tailoring of novels with plots that are reminiscent of another book. For example, Ulysses by Joyce and Homer’s Odyssey.

- Writing books that resemble menus, albums, itineraries, or concerts.

- Anything that can be illustrated. Anything that may suggest the idea that it can be made into a movie.

- Critical essays, any historical or biographical reference. Always avoid allusions to authors’ personalities or private lives. Above all, avoid psychoanalysis.

- Domestic scenes in police novels; dramatic scenes in philosophical dialogues. And, finally:

- Avoid vanity, modesty, pederasty, lack of pederasty, suicide.

The astute reader will find much more of the counterintuitive about this list than its focus on what not to do. Didn’t Borges himself specialize in non-conformist interpretations, especially of existing literature? Don’t some of his most memorable characters obsess over things, like imagining a human being into existence or creating a map the size of the territory, to the exclusion of all other characteristics? Couldn’t he conjure up the most exotic settings — even when drawing upon memories of his native Buenos Aires — in the fewest words? And who else better used myths, metaphors, and games with time and space for his own, idiosyncratic literary purposes?

But those who’ve spent real time reading Borges know that he also always wrote with a strong, if subtle, sense of humor. He had just the kind of sensibility that would produce an ironic, self-parodying list such as this, though history hasn’t recorded whether his, Bioy Casares’, and Ocampo’s young provincial writer would have perceived it in that way or piously honored its dictates. Borges does, however, seem to have followed the bit about never writing “anything that may suggest the idea that it can be made into a movie” to the letter. I yield to none in my appreciation for Alex Cox’s cinematic interpretation of Death and the Compass, but I enjoy even more the fact that Borges’ imagination has kept Hollywood stumped.

Related Content:

Jorge Luis Borges’ Favorite Short Stories (Read 7 Free Online)

Jorge Luis Borges Selects 74 Books for Your Personal Library

Jorge Luis Borges’ 1967–8 Norton Lectures On Poetry (And Everything Else Literary)

Buddhism 101: A Short Introductory Lecture by Jorge Luis Borges

7 Tips from Edgar Allan Poe on How to Write Vivid Stories and Poems

Kurt Vonnegut’s 8 Tips on How to Write a Good Short Story

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply