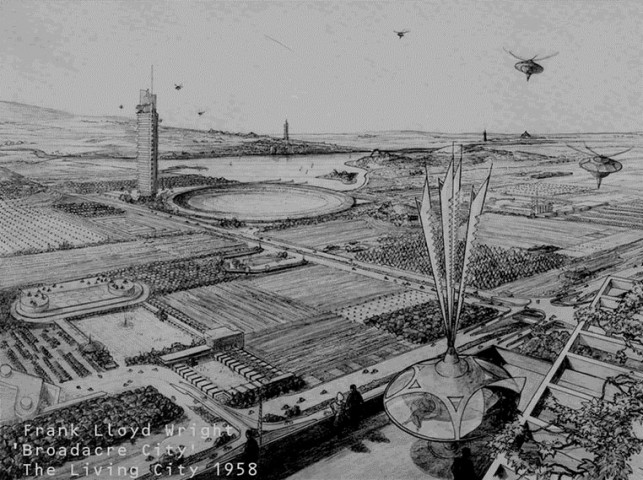

As much as we admire buildings designed by genius architects, we have to admit that — sometimes, just sometimes — those genius architects themselves can be control freaks. These tendencies manifest with a special clarity when a maker of individual structures turns his mind toward building, or knocking down and re-building, the city as a whole. The Cartesian grid of lookalike towers on the green of Le Corbusier’s Radiant City stand (or rather, the project having gone unbuilt, don’t stand) as perhaps the best-known image of urbanism re-envisioned to suit a single architect’s desires. In response, Frank Lloyd Wright came up with an urban Utopia of his own: Broadacre City.

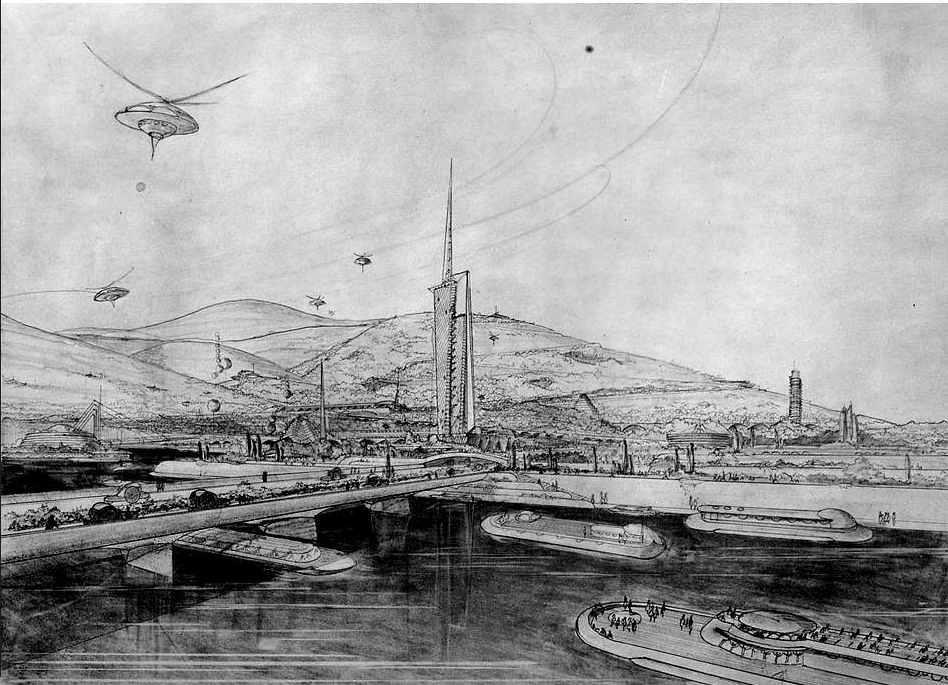

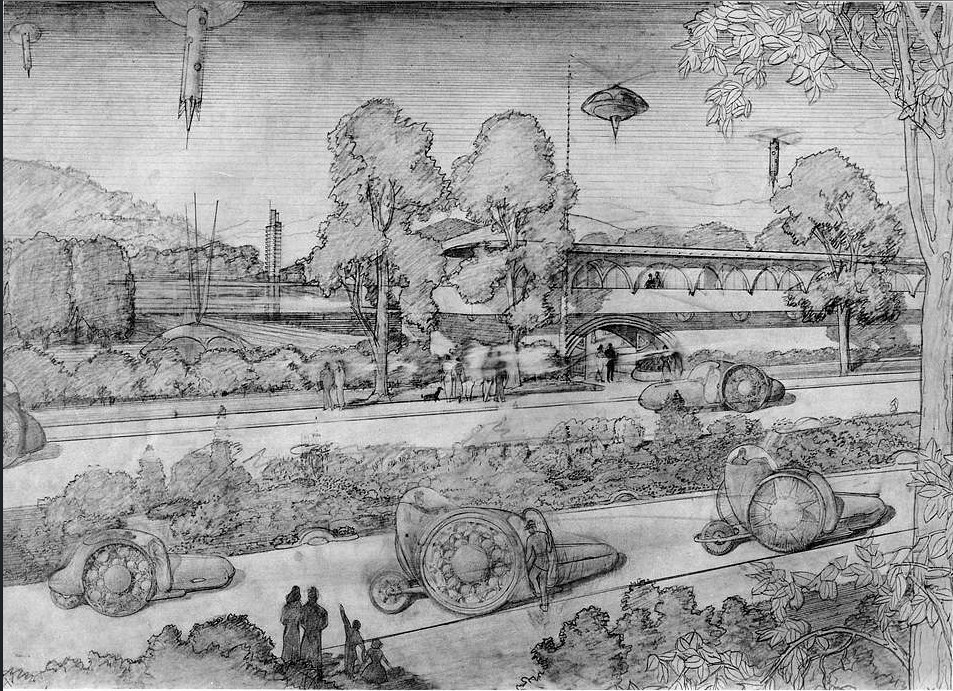

“Imagine spacious landscaped highways,” Wright wrote in 1932, “giant roads, themselves great architecture, pass public service stations, no longer eyesores, expanded to include all kinds of service and comfort. They unite and separate — separate and unite the series of diversified units, the farm units, the factory units, the roadside markets, the garden schools, the dwelling places (each on its acre of individually adorned and cultivated ground), the places for pleasure and leisure.

All of these units so arranged and so integrated that each citizen of the future will have all forms of production, distribution, self improvement, enjoyment, within a radius of a hundred and fifty miles of his home now easily and speedily available by means of his car or plane.”

Those words appeared in The Disappearing City, a sort of manifesto about Wright’s hope for the industrial metropolis of the early 20th century: that it would go away. He “hated cities,” writes The New Yorker’s Morgan Meis. “He thought that they were cramped and crowded, stupidly designed, or, more often, built without any sense of design at all.” Visitors to 2014’s Museum of Modern Art exhibition Frank Lloyd Wright and the City could behold not just Wright’s sketches of Broadacre City but a twelve-foot-by-twelve-foot model of the (to the architect) ideal place, a re-thinking of the urban with the sensibilities of the rural. Almost eighty years before, 40,000 visitors to Rockefeller Center who first saw the model saw it emblazoned with such straightforward declarations as “No slum,” “No Scum,” and “No traffic problems.”

Nelson Rockefeller supported the idea of Broadacre city, as did Albert Einstein and John Dewey, all of whom signed a petition Wright passed around in its favor in 1943. But “even in the 1930s, urban planners were disgusted by Broadacre,” writes Next City’s Katherine Don. “Its philosophy was deeply individualistic; its layout was conspicuously wasteful. Liberals of the time who emulated the socialist spirit of Europe classified Wright as an anti-government eccentric, which indeed he was.” Matt Novak at Paleofuture describes Wright’s utopia as “ultimately an extension of the things that made him personally comfortable: open spaces, the automobile, and not surprisingly, the architect as master controller.”

Though Wright and Le Corbusier “shared an interest in dismantling the recognizable urban fabric, they had different ideas about what should replace it,” writes City Journal’s Anthony Paletta. The architect of Fallingwater thought it best for the city “not to be rationalized but to be pastoralized. Urban ills were to be diluted by ample helpings of prairie soil.” By the time he died in 1958, a sprawling postwar America had wholeheartedly adopted his “new standard of space measurement — the man seated in his automobile.” But nothing as techno-pastoral paradisiacal as a Broadacre ever came into being, and indeed, the suburbs turned out to grow in a fashion even more haphazard and irrational than the one that so disgusted him in traditional cities. Then again, a true perfectionist — and a true artist — must grow accustomed to such disappointments.

Related Content:

Take a 360° Virtual Tour of Taliesin, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Personal Home & Studio

Frank Lloyd Wright Reflects on Creativity, Nature and Religion in Rare 1957 Audio

The Modernist Gas Stations of Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater Animated

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply